By. Katie Rogers, Strategic Energy Innovations

Burs nestled in dog fur. The beak of the Kingfisher bird. Shark skin. These natural phenomena inspired the innovative design of Velcro, bullet trains, and Olympic swimsuits, respectively. Look closely and you will see that nature provides numerous examples of design done well. Engineers, sustainability professionals, teachers, and students are increasingly inspired by biomimicry, “an approach to innovation that seeks sustainable solutions to human challenges by emulating nature’s time-tested patterns and strategies,” according to the Biomimicry Institute.

Recently, Sophia Zug, the Education Program Manager at Strategic Energy Innovations (SEI), led a summer teacher training on Innovations in Green Technology. The week-long training covered a semester of project-based lessons and kicked off with biomimicry in the first unit. Zug explains, “Biomimicry is a really great foundation for students to practice design thinking and to use as a theme throughout the course. As students are thinking about innovative design solutions to challenges we face around climate change and sustainability, using biomimicry as a lens to look for those solutions is, I think, an effective tool for students to have.”

During the biomimicry portion of the teacher training, participants design a device that mimics a samara seed, using just paper and paper clips, and compete to see which design stays afloat the longest and strays the farthest from where it was dropped. It’s a hands-on project that, with little time and resources, gets teachers working collaboratively and creatively. This combination of collaboration and creativity translates easily to the classroom when teachers bring this lesson back to their students. “I think it’s an exciting way for students to think about innovative ideas that’s very approachable,” says Zug. “The teachers see that, and that resonates with them when they are doing the project as part of the teacher training.”

The first three lessons in the biomimicry unit contextualize the need for biomimetic designs by introducing human impacts on Earth, the consequences of climate change for the natural world, and how species have adapted to survive in their environments. Activities include comparing the temperature of two “atmospheres” in bottles, one with extra carbon added in the form of Alka-Seltzer, to demonstrate the greenhouse gas effect; the Carbon Cycle Game, created by Jennifer Ceven, where each student represents a carbon molecule and moves throughout the carbon cycle based on the rolling of dice; and using computer modeling to map evidence of global warming. Finally, students apply what they have learned in a biomimicry design project.

Courtney Watkins, previously a biology teacher and now Assistant Principal of Activities at Calabasas High School in Calabasas, California, worked with SEI to bring the biomimicry curriculum to her classroom. Watkins felt the best way to “pass on the love and the energy and the passion toward trying to do right by the planet” was teaching. When she arrived at Calabasas High, she recognized the need to align the curriculum with Next Generation Science Standards. Watkins dove into SEI’s biomimicry curriculum and recalls thinking, “This is fantastic! So many students get so overwhelmed and their eyes glaze over when we start talking about biology because it’s a different language really. This was an opportunity for me to try out some other curriculum and [the students] just ran with it. They had so much fun, they were like, ‘Wait, we get to build stuff?!’” Watkins’ students tackled newsworthy environmental issues of the time, including ocean plastic, oil spills, and household water consumption.

In her new role, Watkins now works closely with student government and environmental clubs to spread information and influence behavior change. She is proud of her students, who are now graduating college and entering planet-loving professions like marine biology and environmental policy, for maintaining a hopeful attitude in the face of overwhelming environmental challenges.

Alex Robins, a teacher in the School of Environmental Leadership (SEL) at Terra Linda High School in San Rafael, California, integrated SEI’s biomimicry curriculum into his tenth-grade Environmental Leadership seminar. With a master’s in history, Robins approaches teaching biomimicry from a layman’s point of view. “I think it was actually in some ways quite helpful because I was able to approach it from more of a ‘Tell me about this. What is this?’ perspective.” Learning alongside his students has been a positive experience for Robins. “It was much more collaborative and kind of experimental,” he reflects.

Challenged with using biomimicry to address climate change, Robins’ students researched how the natural systems around us are inherently sustainable. The students came up with a wide array of creative projects, including carbon-absorbing pods based on the mechanics of a Saguaro cactus and earthquake-resistant construction inspired by porcupine quills. As a culminating activity, students submitted their projects to the Bioimicry Institute’s national Youth Design Challenge.

In their junior year, SEL students build a sustainable enterprise – raising capital, creating a business plan, and bringing their product to market – and biomimicry primes the students to create a business based on design thinking. Robins says, “I found it to dovetail well into the idea of design thinking, which is a lot of the class, and thinking about sustainable practices and policy rather than just like ‘oh, recycling.’”

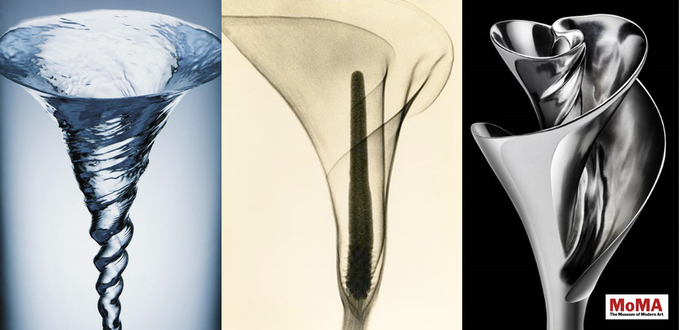

To help his students see how biomimicry might be applied beyond the classroom, Robins calls on industry professionals like Francesca Bertone. Bertone is Chief Operating Officer at PAX Scientific, an engineering research and development firm based on biomimicry. PAX’s latest innovation is a fan inspired by nature’s vortexes that uses 85% less electricity than conventional fans, which haven’t seen design innovations in over 100 years. Bertone started her career in education and loves sharing biomimicry with students. “We speak all over the world. We work with engineers in some of the largest corporations in the world. And I do some of the same exercises in those corporations as I do at Terra Linda High School, and those kids wipe the floor with what the executives can do,” Bertone reports, impressed.

From Bertone’s perspective, teaching biomimicry is important because it refines students’ communication skills by requiring them to be precise with their language and metrics, encourages creative solutions and innovations, and promotes patience with complex processes and systems. The fundamentals of biomimicry education – analyzing what you’re trying to achieve, thinking deeply, looking at things systemically – make for a better thinker, she argues. “[Biomimicry] is absolutely teachable and it is so important regardless of the field that a student goes into. You can learn from nature whether you want to be a lawyer or an engineer or a chemist or you’re running your own home. There’s so much we can learn, it’s invaluable. I genuinely believe that.”

Author Bio

Katie Rogers leads communications and marketing efforts for Strategic Energy Innovations (SEI), a nonprofit organization that builds leaders to drive climate solutions through environmental education and green workforce development. She supports SEI’s program teams working on a variety of environmental education and sustainability capacity-building projects. Prior to joining SEI, Katie worked in marketing and advertising in California, New York City, and Seattle. Katie holds a Masters of the Environment degree in Sustainability Planning and Management from the University of Colorado, Boulder and a Bachelor of Arts in Communications and Anthropology from the University of California, Santa Barbara.