By. Andy Barker

As Project Director of an immersive, place-based, experiential high school program, I was as unprepared as anyone for school to shift online last spring when the COVID-19 pandemic arrived in Vermont. I often say that our program, the Burlington City & Lake Semester (BCL), “uses the city as our classroom.” Last March, that became impossible. So, in the space of a few days, our faculty team essentially redesigned the last half of our semester program for virtual learning. (Fortunately, every one of our students had a working Internet connection.)

The rapid makeover felt fairly chaotic at the time, especially as we worked by videoconference with our own young children occasionally in the background. But in retrospect, our approach was to build from our program strengths to create an online experience that still honored BCL’s core design principles. Here are my top takeaways from the experience.

Prioritize Relationships

It’s harder to make positive social-emotional connections online. As an experiential program, that’s our bread and butter. So, our team’s first priority was to adapt most of our community-building practices for virtual learning. We began every online class with a brief Morning Meeting, including a student-led check-in question, answered by everyone, in turn. (Examples: What’s a plant or animal that you feel a connection to? Who’s one of your heroes?) It’s a simple way to greet each other in the digital space and invite everyone’s voice into the conversation. Importantly, it opens up space for student creativity, personality, and humor, but the stakes are low. Students want to hear each other’s responses, so they begin every class engaged and listening to each other. I consider it an essential practice for online school.

Other simple relationship-building ideas include asking students to keep their laptop cameras on (though only if they feel comfortable doing so); greeting everyone by name as they join each call; and having at least one direct, personal touch with every student each week.

Real-World Experiences are Still Possible

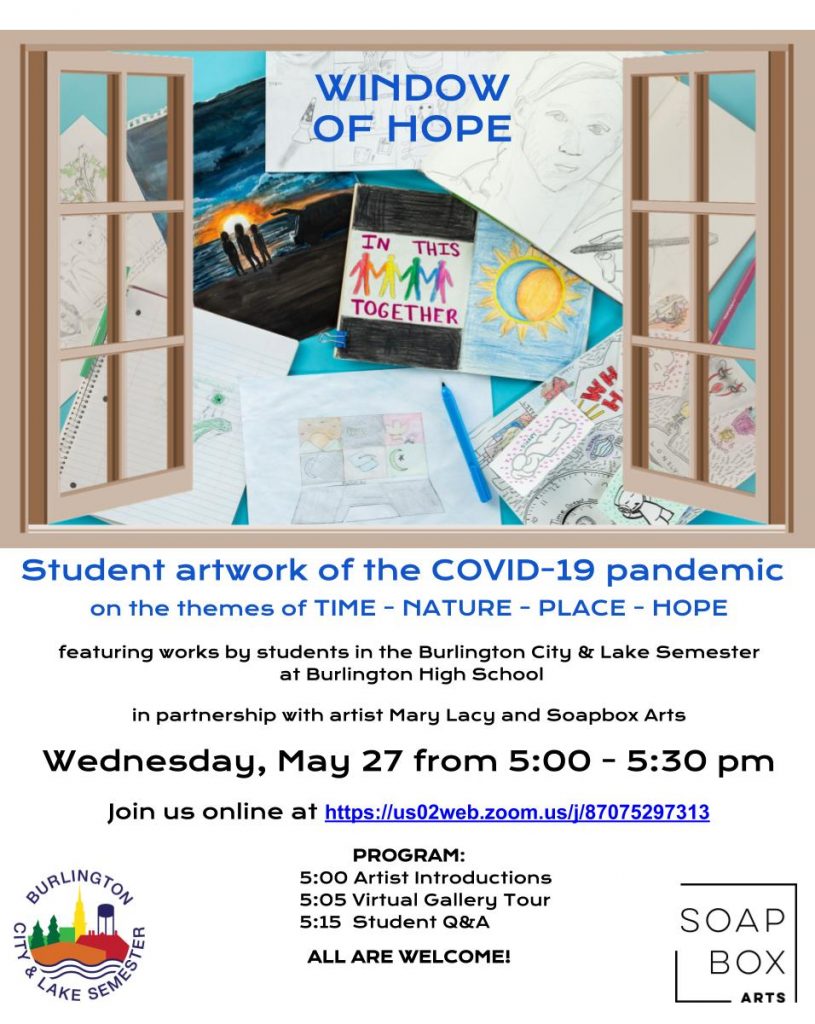

Even when a class can’t be together, there are ways to make sure students are engaged beyond their bedroom. We invited students to tune in to the arrival of spring with a Phenology project, with periodic call-ins from a local naturalist. We introduced them to the iNaturalist app and encouraged them to get outside – even in their own backyard – and journal about the changes happening in the natural world. We also forged ahead with a planned art project. Students met virtually in small groups with a teaching artist and we shifted the project’s focus to documenting students’ experiences of the pandemic. Each student worked on their own artwork, from sketches and photography to painting and written words. Then, students collaborated to create a website, produce a short film, and publicize and host a virtual gallery opening for 100 attendees. Every part of the project invited students to practice and develop transferable skills.

Shorten Everything that’s Online

We all know how slowly time can pass in an online meeting. So we found it effective to plan online classes like a late night comedy show, with several short segments, many different voices, and some kind of visual interest. BCL faculty took turns hosting calls and we shared leadership for each class element (e.g., news, mini-lecture, discussion, and project updates). We aimed for five minutes for any given segment; longer was okay if students had some kind of active role. We also found it helpful to have one faculty person keep their microphone turned on so they could respond and react to the leader in real time. This chased away the dreaded silence that often makes online classes feel so flat.

Keep Students Actively Participating

In our in-person program, we want students to be doing much more than listening and watching. We tried to uphold the same standard with BCL Online. One big success was our adapted journal practice. This was usually framed by a faculty member with a news item or an article summary followed by a specific prompt. For five minutes, sometimes longer, we all wrote silently together online. Then we did a sharing round, where students read at least one sentence from their writing. This activity captured the feeling of being in-person more than anything else we did. The shared silence, the shared task, the open-endedness of a journaling session, and the personal act of sharing one’s words was very effective. We had some flops, too. We couldn’t get discussion going on our online calls, even with a juicy prompt or question.

Adapt Discussion

Groups of more than a few people can struggle to have a real discussion online. One simple approach we used to minimize air time but still create an inclusive give-and-take was to hold a ‘discussion’ in real time on a shared Google Doc. The teacher invited everyone on the call to type a one to two sentence response to the news story under their name in a shared, pre-formatted Google Doc. Everyone silently read what others had written on the document and the leader invited one or more rounds of written responses. (We used the comments function for this.) It was a surprisingly effective way to engage students and generate some of the intellectual energy of a discussion without bogging down the call. As a way to wrap up, the teacher would highlight students’ ideas from the Google Doc.

Create Small Groups

For all but the most confident students, it’s intimidating to speak up in an online class. Reducing the social risk of participation is essential. We convened small groups for this purpose on a regular basis. An added benefit was that it helped to balance out air time among students, though it required more time from faculty. All of our project-based work happened in small groups.

Stay Student-Centered

Inquiry cycles are a mainstay of our in-person program, and they translated well to virtual learning. In the simplest version of Inquiry, students identify a question they are curious about and then use experiences, interviews, or other research methods to explore their question until they can frame a deeper, more sophisticated question. At cycle’s end, students present the story of their learning journey to their classmates. We continued with Inquiry cycles after going online, with students shifting to remote methods to conduct research. We also adjusted the depth, timeframe, and output of each Inquiry cycle to meet the capacity of each student. For some students who struggled with mental health during the COVID-19 lockdown, for example, we coached them through each step individually and allowed them to make a presentation to a teacher, rather than to the whole class.

Widen the Circle

One advantage to going virtual is that it allowed us to access people who we could have never met in person. We had several online classes with a group of Danish students who shared their perspectives on life during the pandemic. If we go back online again, we will look for another class to partner with in a similar way.

Ask Students What’s Working – and What’s Not

Our team has used exit cards and surveys on a regular basis to get direct student feedback on our program. We increased the frequency of our surveys while we were online since we were trying so many new things at once. Student input, and our efforts at continuous improvement, guided us toward many of the insights in this article.

As I write in mid-August, we are planning to meet in-person this fall, with a new group of students. But if we have to return to virtual learning, we have some tried-and-true approaches to pursue compelling, place-based education at the high school level. It’s more important than ever.

To learn more about BCL, please explore our blog or visit our website.

Author Bio

Andy Barker is Project Director and co-founder of the Burlington City & Lake Semester, an immersive, place-based program for juniors and seniors at Burlington High School, in partnership with Shelburne Farms. He has worked in education and socially responsible business for 25 years. He taught history at the Maine Coast Semester in Wiscasset, Maine and was a ‘DaVinci’ humanities teacher at the Gailer School in Shelburne, Vermont. For 11 years, he worked on Ben & Jerry’s Social Mission team, creating partnerships and campaigns to support a sustainable food system, a stronger democracy, and social and economic justice around the world. He is excited to be an innovation partner for Burlington schools.