By. Qiana Spellman, Ed.M.

As educators, we often find ourselves searching for ways to make students’ educational experiences more valuable. We contemplate how to create new initiatives, which programs we can enhance, or what classes we can improve. This is especially needed right now. The need for rich, academically stimulating classes that speak to the reality of Black and brown student lives has reached a boiling point. The current social and political climate of our country leaves students yearning to find their voice as they grapple with the realities of Black lives being lost at an inexplicable and disturbing rate, their communities being disproportionately affected in almost every health and wellness aspect, and an educational uncertainty that has now been intensified. Thus, we find ourselves in a position to recreate classroom culture and student experience using a sociocultural lens that builds upon students’ prior knowledge, their culture, and their lived experiences.

Implementing Culturally Relevant Teaching

While school counselors traditionally don’t teach classes, we are in a unique position to “illuminate and eradicate equity gaps” as we are “called on to challenge the status quo” and affect change on multiple levels (Stone, 2016). With a deeper understanding of what our students struggle with and long for, counselors can craft an academic experience that bolsters student engagement and reinforces collective empowerment. Through the implementation of Culturally Relevant Teaching (CRT), counselors can serve as exemplars on how to bridge socio-emotional awareness with academic success, cultural competence, and critical consciousness. According to Ladson-Billings (1995b), CRT is a “theoretical model that not only addresses student achievement but also helps students to accept and affirm their cultural identity while developing critical perspectives that challenge inequities that schools (and other institutions) perpetuate.”

Year after year, I listened to students express their discontent in the lack of relevant curriculum that schools offer to meet their intellectual and social-emotional needs. Students spoke of glossed over history lessons that omitted relevant information, essentially negating their cultural legacies and ignoring the trauma inflicted on generations of their people. This, of course, extended throughout their entire educational experience. Further, everyday discussions led to a realization that at 16 and 17-years-old there were names and major historical events that my students weren’t familiar with. Recognizing the gap and a need for student voices to be heard, I created Race in America, a social studies credit-bearing elective class that I would teach.

Race in America in the Classroom

Using CRT to inform my pedagogical practice, Race in America is rooted in an examination of the origins of racist ideas in America. Based heavily off of Ibram X. Kendi’s book Stamped from the Beginning: The Definitive History of Racist Ideas in America, students engaged in an intense dissection of where racist ideas stemmed from, what drove this ideology, and the underlying meanings and constructs of race in this country. Topics throughout the semester further examined the juvenile justice system, mass incarceration, the concept and effects of “white privilege,” Black and Latino civil disobedience movements, and the psychological and emotional tolls these issues take on the teenage psyche. Additionally, a partnership was formed with the Brooklyn Academy of Music, as we implemented the Brooklyn Reads program, which utilized spoken word poetry and hip-hop to address socio-political topics that resonated with students. Socially charged poetry and vivid lyrics offered students a historical perspective that could be delivered in a manner familiar to them. Writing exercises provided a safe space for students to express their emotions and use writing as a therapeutic tool.

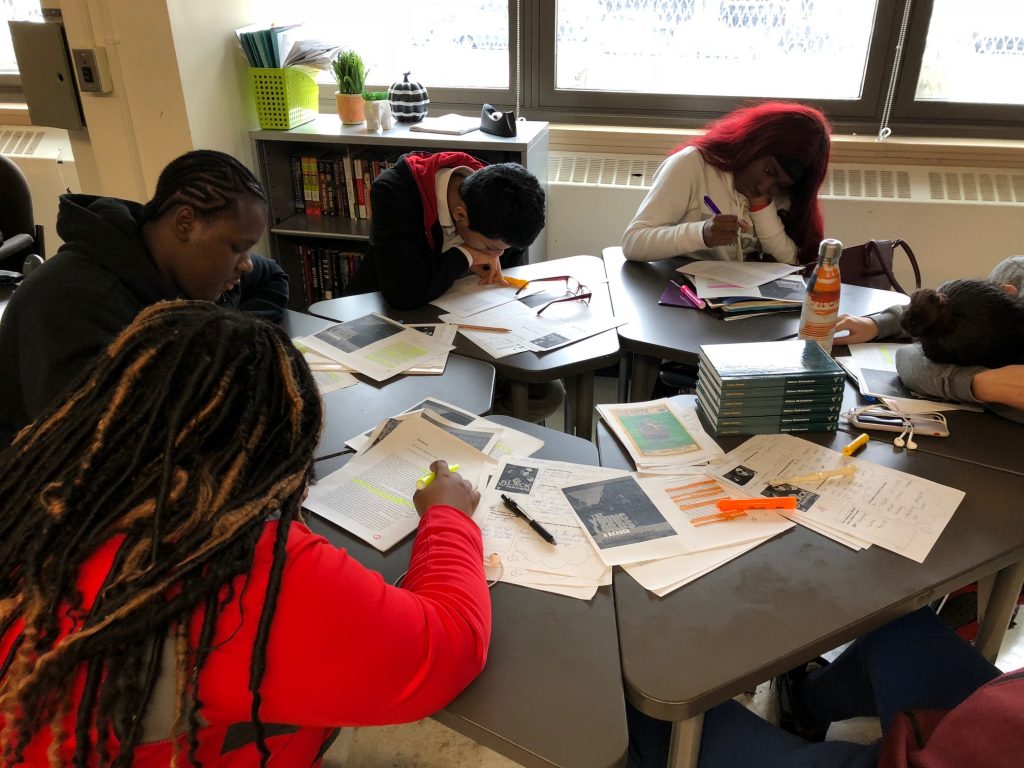

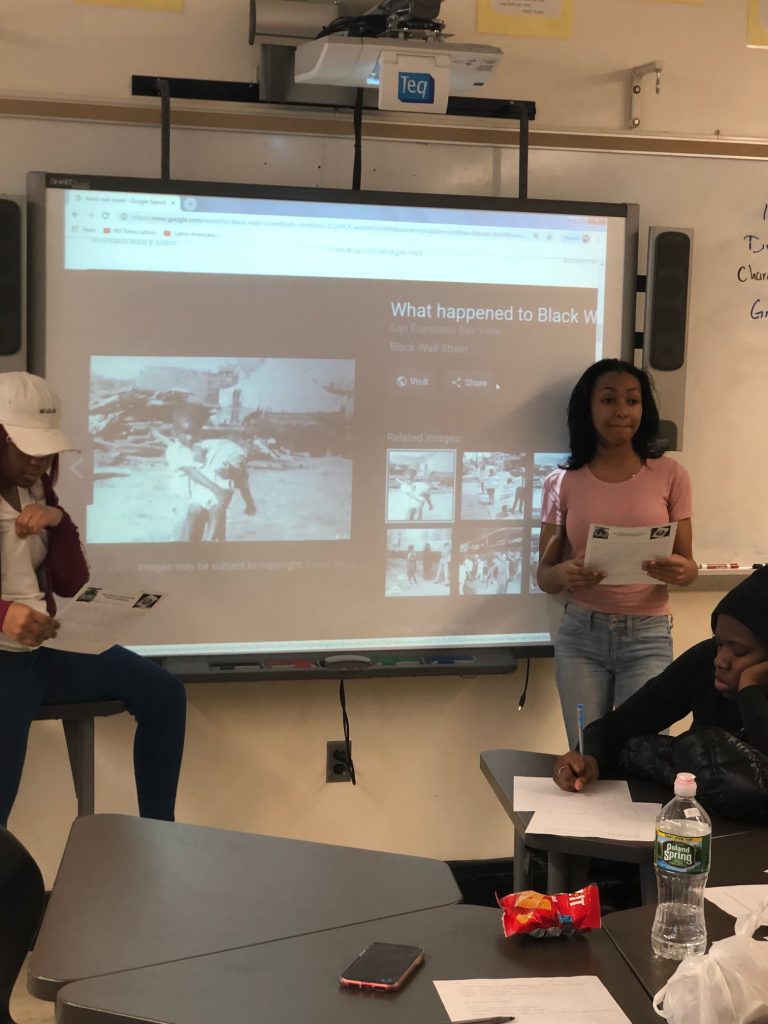

Throughout the semester, students engaged in discourse, developed critical thinking, and reflected on how topics addressed in class impacted their thoughts and feelings on race. Students led discussions and gained equity in the class, as their voices and opinions were valued and respected. Through independent and group research projects, students analyzed various forms of texts and documentaries, while making direct connections to the materials. Students were exposed to information they wouldn’t normally receive in their traditional social studies classes and contributed to the curriculum by requesting topics to cover throughout the class’s duration. For many counselors, creating and teaching a class seems outside the scope of their job requirements. I had to reconcile that, in these times, it was essential to go beyond these requirements to ensure students received the type of education that would make them fully whole.

Best Practices

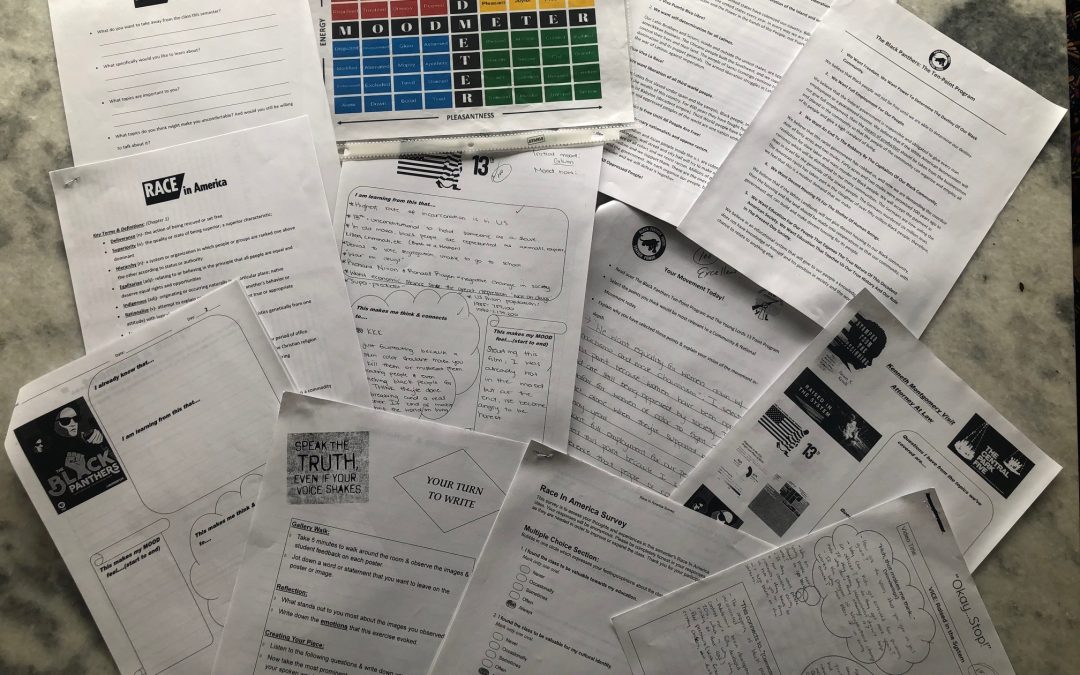

When investigating highly sensitive topics, it’s imperative that educators do so responsibly. Understanding that subject matter can be triggering, one must be mindful of students’ emotional processes and well-being. At the start of every class, I placed a mood meter on each desk or shared table. Students were asked to jot down where they fell on the mood meter upon arrival to class and at the close of class. This allowed me to gauge the emotional temperature of the class in real time, while remaining cognizant of how students were affected by the lessons. With that being said, it’s also essential to allow students the time to feel the emotions that come along with the topics and information being shared. Don’t be afraid of your students becoming emotional or think a topic is too heavy to address. Rather, allot time for this natural process to occur. Allow students to engage in healthy discourse and provide time for written reflection.

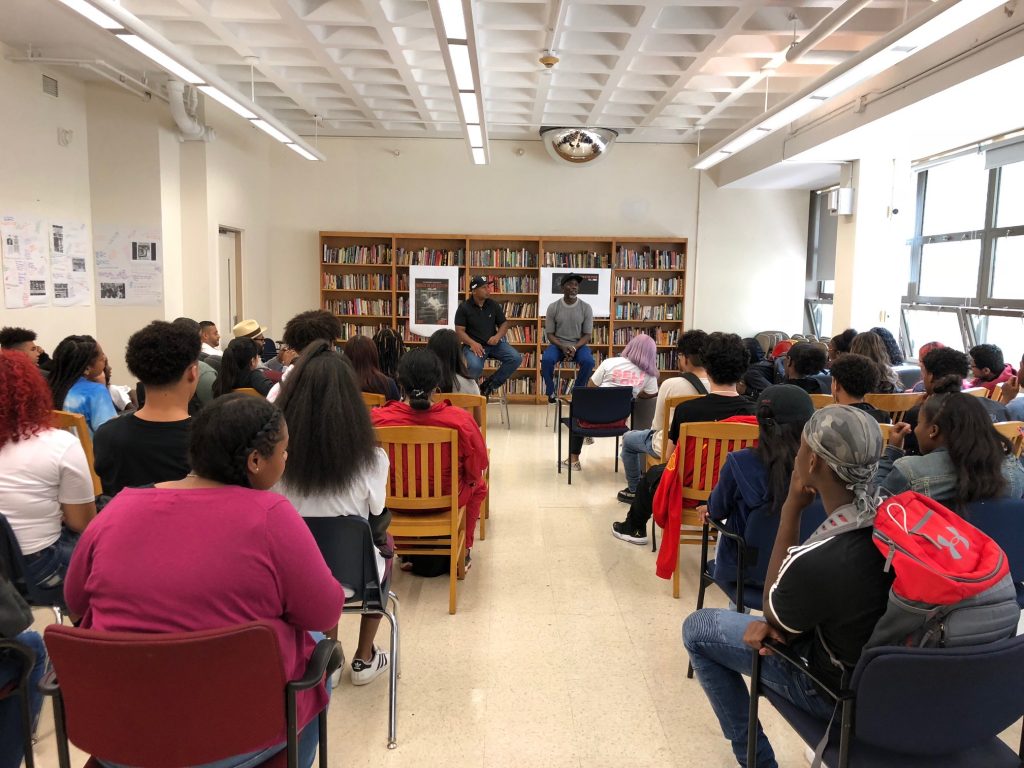

We cannot be experts in all things, so it’s ideal to enlist the support of others. I sought the expertise of those in my network to keep my class authentic and stimulating. Guest speakers who can visit your class and speak to your students from a lived perspective offer social capital that can be inspiring. For Race in America, guest speakers included a high-profile Black defense attorney and the Emmy-nominated actor and producer Michael K. Williams. These visits offered students invaluable experiences, as they were able to engage with each speaker on a very personal, yet informative level. Both visits directly connected to the content areas being covered in class. Additionally, it can be beneficial to utilize the knowledge base of your colleagues. During the planning stages of Race in America, I asked my Assistant Principal if she would be interested in teaching the unit on Latin American History, as she has a strong connection to the culture. She agreed and brought a vital element to the class that allowed our Latino students to feel further included.

Lessons Learned and Takeaways

When creating a class rooted in social justice such as Race in America, it’s important to include a historical lens that encompasses all students in the room. With a demographic of Black and Latino students, I had to ensure all my students felt included in the class and manage any concerns regarding potentially catering to one group more than the other. Per Emdin (2016), valuing students’ voice provides “students with an opportunity to have their thoughts, words, and ideas about the classroom and the world beyond it heard and incorporated into the approach to instruction” (p. 59). Students then become empowered, gaining a sense of agency and freedom of expression. In my class, this awareness created an environment that challenged everyone to take an in-depth look at the unique histories of Black and Latino populations, while gaining perspective on the similar struggles that both cultures have faced in this country. Remaining aware of the cultural differences and similarities that students may experience is vital to maintaining a healthy and equitable class. Thus, it may be necessary to remind students to be mindful of others’ cultures and not diminish the importance of engaging in the learning process. Due to the deficit that often exists in schools surrounding Black American and Latino history classes, students at times were so engrossed in learning about their own culture that they didn’t want to take a break to learn about another. The consensus of the class ultimately became a request for Race in America to become a year-long class rather than a single semester.

Lastly, allow current events to drive your lessons. If an event or a situation occurs that requires attention, address it in real time with your students. Create a lesson around the issue or event that has taken place or connect it to another lesson you had planned. Ignoring the elephant in the room just to stick to a lesson plan is in direct opposition to the nature of this work. Flexibility is not only key but necessary. Further, offer your students a choice in what they want to learn about or spend more time on, allowing them to feel as if they have a stake in the class. This will garner integrity, as students choose academic excellence and develop a broader socio-political consciousness (Ladson-Billings, 1995a). Ensuring that students receive a robust and meaningful educational experience is not only the goal, but the driving force of my work.

References

Emdin, C. (2016). For White folks who teach in the hood…and the rest of y’all too: Reality pedagogy and urban education. Boston, MA: Beacon Press.

Ladson-Billings, G. (1995a). But that’s just good teaching! The case for culturally relevant pedagogy. Theory Into Practice, 34(3), 159-167. https://doi.org/10.1080/00405849509543675

Ladson-Billings, G. (1995b). Toward a theory of culturally relevant pedagogy. American Educational Research Journal, 32(3), 465-491. https://doi.org/10.3102/00028312032003465

Stone, C. (2016). Cultural competence and ethical action. Can’t have one without the other. ASCA School Counselor, 6-7. Retrieved from: https://www.schoolcounselor.org/asca/media/asca/ASCAU/Cultural-Competency-Specialist/EthiicalAction.pdf

Author Bio

Qiana Spellman, Ed.M. is a school counselor and educator at a high school in Brooklyn, New York. She holds a Bachelor of Science degree from Xavier University of New Orleans, a master’s degree from Long Island University, an Advanced Certification from Hunter College, and is currently completing her Doctorate in Education from Teachers College, Columbia University. Qiana’s research focuses on the dynamics of school counselors as educators, social justice related initiatives, and the use of hip-hop in education.