By. Dina Sorensen and Maria Burke

This brief essay isn’t intended to reiterate the long history of design thinking as best expressed by the brilliant David Kelley, founder of IDEO and the Stanford d.school, as there are numerous resources readily available for educators. Instead, it’s meant to complement the growing use of the design thinking methodology in education by highlighting its transformative role as a co-creative process in the development of a learning community.

At its core, design thinking is all about using creativity and empathy to solve problems. Unlike the engineering design process, the first step in design thinking involves empathizing with the intended end users to better understand their needs and experiences. Once the problem is established, it’s further defined and refined before ideas are generated, prototyped, and tested. The ‘designing’ of solutions involves iteration, reflection, communication, and sharing of the knowledge that emerges from the process – all while strengthening effective collaboration skills. For the purpose of this essay, we step back and ask the following question: how might the design thinking method, as a human-centered approach to learning, inspire new ways for students to fully connect to a greater identity as a contributing member of their learning community?

Design thinking is making greater strides into K-12 and Higher Education – and with good reason. It has the power to transform traditional teacher-guided instruction into a student-led learning experience – one that is engaging and motivating for all people. As a learning environment project designer in the field of architecture, I collaborate with educators, researchers, and experts from a wide range of fields to facilitate grand design challenges using the design thinking method. I have seen how rewarding it is when traditional roles are reversed, when students become experts of their learning and teachers set the stage for interdisciplinary collaboration with outside experts. It’s from this point of view, as an ‘outside expert’ coming into schools to be part of a design challenge, that I know we can all contribute to the important shift in education from teacher-led to student-led learning and that design thinking becomes key in “…linking into society or an authentic purpose – giving the students a legitimate role (task) in society through community participation/membership and giving the to-be-learned content consequential value” (Land, 2012, pp. 58-59). When students engage in a design challenge, they shape the relevance and meaning of the project and define and propose solutions that make a positive impact in their community. This is the inherent power of leveraging the design thinking method – the participatory creation of usable knowledge fosters a school culture of creativity and agency as students and teachers live out and share meaningful learning experiences.

The design thinking method that allows designers and architects to realize complex, real-world projects is adaptable for K-12 education as “a systematic innovation process that prioritizes deep empathy for end-user desires, needs, and challenges to fully understand a problem in hopes of developing more comprehensive and effective solutions” (Roberts et al., 2016, p.12). In other words, a solution to a problem is not readily apparent but evolves by way of a co-creative process – a form of collaboration that directly involves an end user’s creative problem-solving skills – not just their insight. What we have translated most widely for K-12 student-led design challenges strives to capture 21st century learning competencies (creativity, communication, critical thinking, collaboration, citizenship/culture, character) by supporting educators with a design framework to identify and address the ‘grand challenges’ that live at the heart of their communities (Burke, 2019). What differentiates design thinking from test taking is the real need to challenge most assumptions when transforming a problem statement or need into a design challenge. By going through the iterative phases, it starts to awaken innovative problem-solving and critical thinking skills. The benefit for students is what we know from neuroscience and learning, as well as in the design profession: the iterative process promotes a growth mindset as ‘failure’ is no longer stoking fear of having the wrong answer but rather is a function of developing deeper learning skill sets. The phases of discovering and researching, re-framing problems and needs, developing and testing strategies, iterating (prototyping) ideas, communicating the value of proposed solutions, and then building as a community fosters a growth mindset culture. Why does this matter? Like the learning process, great design thinking inherently asks how something connects with the world around it and how the relationship between the design solution and its context changes over time. We know learning is not linear. It’s dynamic, and when “human-centered design offers problem solvers of any stripe a chance to design with communities, to deeply understand the people they’re looking to serve, to dream up scores of ideas, and to create innovative new solutions rooted in people’s actual needs” (IDEO.org, 2015, p. 9), it has the potential to strengthen the connection between students and their physical environments.

One example of how design thinking can influence learning at the community scale can be understood through Arlington, Virginia’s Discovery Elementary School Student Design Challenge. The challenge started in 2017 as a fifth-grade design challenge to reimagine a school space through the concept of furniture (Sorensen, 2017) and involved a diverse team of educators, designers, and researchers who brought design thinking into the school. In the course of three years, the challenge has evolved to become the all school Mastery Project for all grade levels. In its most recent rendition, a teacher’s guide has been created for each grade level to scaffold student learning through the design thinking method, tied to the National Wildlife Federation’s Pathways to Sustainability, to solve place-based and local challenges. As an example, second-grade students audited the stormwater pathway to sustainability. Through their research, they decided to solve a place-based problem around the school facility’s stormwater outlets. The students also noticed trash around the school grounds and wondered what would happen if it wasn’t picked up. In conversations with invited guests from the Arlington Department of Environmental Services, they learned more about the county’s stormwater system and brainstormed how to raise community awareness of trash ending up in the local watershed during the coming rainy season. Students then learned that RainWorks was an invisible paint product that only becomes visible when it gets wet. They were able to select one of Arlington County’s approved designs to paint on each storm drain while also designing their own stencils based on what they researched and thought would be most impactful.

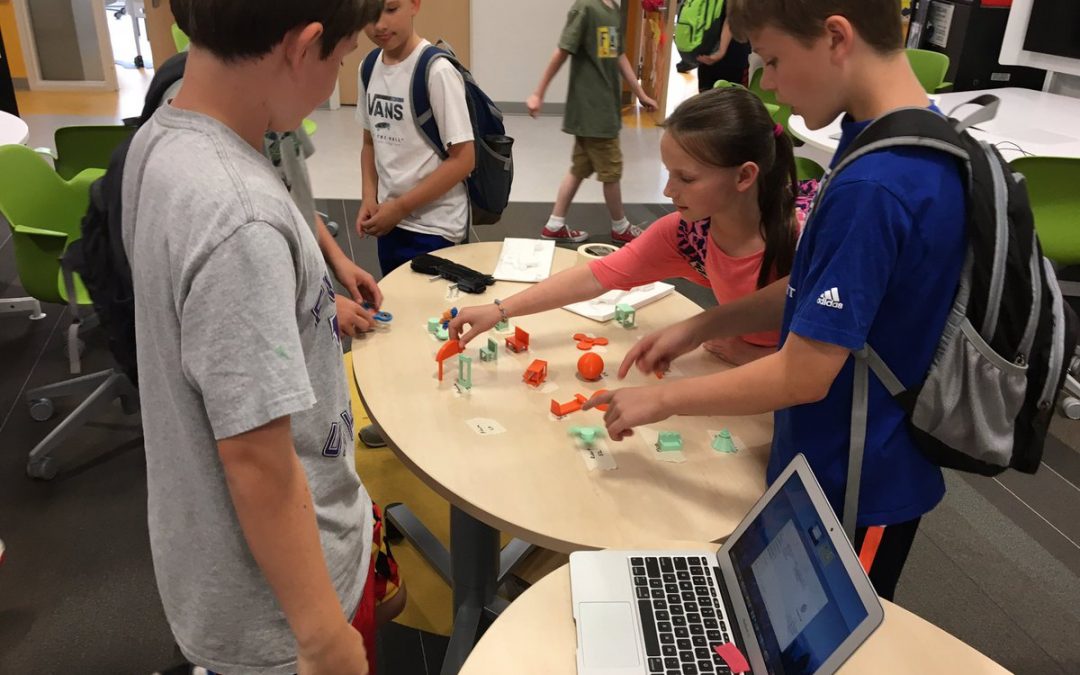

Creative and innovative problem-solving using the design thinking method as demonstrated in Discovery’s Student Design Challenge points to the heart of the design experience – giving students the ability to engage in and modify their environment (Burke, 2018). It requires empathizing through research; discovering through interviews with students, staff, and others about their needs; and then coming up with concepts that require investigation, experimentation, and making (or modifying) the environment to initiate positive change. As such, the whole of the physical environment begins to function more as a teaching tool. Curriculum that embeds design thinking as a way of engaging with the environment gets back to the root of creativity and imagination where learning is a form of experiential play or gaming. When students move from concept design to small-scale rapid prototyping to a full-scale mock-up of their designs, they experience what it means to first tackle a problem with novice skills and expand those skills by moving through the process. The learning outcomes are process-oriented as students interact with ideas that come to life with meaningful significance.

This depth of community learning through tinkering, building, and creative integrity was on full display when a small group of Discovery fifth-grade students rallied around the task of creating a swing seat – a seat base with a rope that could hold a person or two off the ground. I was told by teachers, who marveled at what they saw happening, that those same students had never talked to each other during the school year because of social differences. It was the sharing of ideas and potential solutions and working on problems together that made them excited to help each other foster even more ideas. They may not have known that before, but in the process of co-creating a solution they were motivated by the recognition that the outcome was going to be useful, much more so than if they were working on it alone. The swing seat ended up becoming the main innovative feature for the new design and was highly valued among the students. When one student had to focus on driving a screw, another one offered to hold her ponytail out of the way so she would be safe. These small relational breakthroughs are as much about the process as the outcome itself. The students succeeded in creating a swing seat that was well-designed, well-built, and worked!

Another benefit of using the design thinking method is an increase in design thinkers as engaged citizens able to tackle ‘grand challenges’ in the built and natural environments. This shift is a deep consideration for schools looking to create new traditions as the complex challenges our students will face in the world cannot be solved with traditional approaches. Modern challenges require interdisciplinary collaboration and call for a new kind of practitioner in any field with creative and specialized mastery. Globalization itself reinforces the importance of a community of learners to reflect, engage, and co-create meaningful solutions as a form of engaged citizenship. Providing students with the opportunity to use empathy as a strategy to connect to relevant issues in a visceral, hands-on way begins to build a collection of learning experiences that share the community’s goals and values. This is illustrated in another Discovery Student Design Challenge that focused on creating a new space for expeditionary learning in the woods. The small remnant wooded area was one of the few remaining in an increasingly urbanized site and had yet to be adopted by the school as an asset or teaching tool. Student research focused on what the learning community needed but also integrated the interdependent needs of other species. Students set up nightcams to observe what was happening at night and recorded animal activity much to their surprise and delight. In the process of this new biodiverse discovery, one student was so moved by seeing nocturnal animal activity that her small rapid prototype designs began to adapt and take on new features that would allow the end product to serve as an animal feeding habitat during the night and a reading bench for students during the day. The design innovation was astounding.

Fostering a design thinking mindset and helping students to engage in the power of a communal experience points to a broader responsibility to commit to authentic problem-solving, adaptability, resilience, and empathy as a visible embodiment of that commitment. Our students today will become compassionate citizens of our world tomorrow and design thinking is one method to help future fit this undertaking. It’s a work in progress, as teaching and learning practices evolve and students are afforded opportunities to truly engage in their creativity, imagination, and unique talents to make a difference in their communities and beyond. The real world awaits these creative, confident learners.

Works Cited

Burke, M. (2019). Art and Biomimicry Collide to Create Discover Elementary School’s “Nature’s Hideout” [Web post]. Retrieved from: https://greenschoolsnationalnetwork.org/art-and-biomimicry-collide-to-create-discovery-elementary-schools-natures-hideout/

Burke, M. (2018). It Takes Community to Create [Web post]. Retrieved from: https://medium.com/@burkefamily711/it-takes-community-to-create-ce606c77b238

IDEO.org. (2015). The Field Guide to Human-Centered Design. IDEO.org.

Land, S. (ed). (2012). Theoretical Foundations of Learning Environments. New York: Taylor & Francis. Routledge.

Roberts, J., Fisher, T., Trowbridge, M., and Bent, C. (2016). A design thinking framework for healthcare management and innovation. Healthc (Amst), 4(1): 11-4. doi: 10.1016/j.hjdsi.2015.12.002

Rosales, J. (2017, February). Education By Design: Challenging the Traditional Definition of a Learning Space [Web post]. Retrieved from: http://neatoday.org/2017/02/21/school-design/

Sorensen, D. (2017, December). Think. Make. Do: Students at Discovery Elementary School SHINE as Expert Designers! [Web post]. Retrieved from: https://webspm.com/articles/2017/12/06/design-challenge.aspx

Stanek, C. and Moran, P. (2019). Multidimensional Learning: Using School Grounds as a Tool for Learning Sustainability Concepts. Green Schools Catalyst Quarterly, VI (1), 86-99. Retrieved from: http://catalyst.greenschoolsnationalnetwork.org/gscatalyst/march_2019/MobilePagedReplica.action?pm=2&folio=86#pg86

Author Bios

Dina Sorensen, Associate AIA, LEED AP BD+C, brings her unique background in the arts, architecture, and interdisciplinary research to enrich the design of learning environments. As a designer, author, and speaker who spearheads interdisciplinary collaboration, she focuses attention on the human experience while aiming to co-create learning spaces that foster agency, creativity, diversity, and a symbiotic relationship with nature and technology. Her primary research investigates the influence of design on healthy behaviors and catalyzing connections between public health and architecture.

Maria Cuzzocrea Burke is a Visual Art Teacher at Whittle School & Studios in the Washington D.C. area. She is the mother of an Appalachian Trail thru-hiker and an active member and presenter at the Virginia Art Education Association and National Art Education Association’s conferences.