By. Dr. Kay Sturm

As I write this, teachers are preparing for the unknown landscape of virtual or hybrid education in the 2020 – 2021 school year. For many teachers, summer was cut short from an average two-month to a hopeful one-month reprieve, with preparations, training programs, personal research, creating new materials, and learning new technology consuming much of their time.

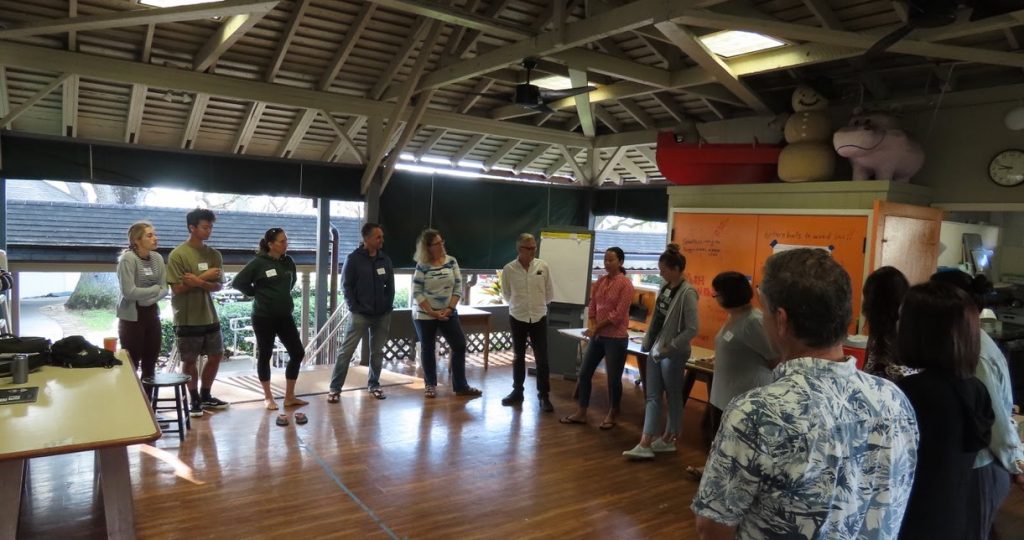

This summer, I spent a lot of time with these hard-working educators on their “summer breaks.” In June, with school barely over, I trained teachers from all over the world at the first online PBL World conference. Later that month, I trained teachers in Japan’s DoDEA system who wanted to learn more about integrating project-based learning into their pedagogy. In early July, I worked with teachers in Hawaii the day after they found out that they would be moving to a hybrid system, or a combination of asynchronous and in-person learning (this has since changed to 100% distance learning). In all these occurrences, teachers were not only asked to learn new content, they were also asked to apply new ideas to their teaching practices, develop resources for their students, and learn to navigate multiple online platforms that were the basis of the workshops – all at the same time. No matter where in the world the educators I train are from, there’s one undeniable fact – they will adapt. However, in all our efforts to support students and avoid cognitive overload, we cannot ignore the cognitive demand that is occurring for our teachers.

The Impact of Big Decisions

There’s been a lot of talk since March’s COVID-19 outbreak about how best to deal with the situation for the safety and well-being of students and staff. There are some who say that this is an opportunity to change the education landscape completely, while others, like parents, are taking the situation into their own hands and creating education pods or enrolling their kids in homeschool. There are others who are trying to revert to the most “normal” situation by making decisions that create the least impact.

So let’s consider the impact of the systemic decisions that are being made at higher levels:

When schools and school districts make the decision to go to 100% virtual learning, teachers have to:

- learn how the technology works

- learn how to create powerful learning experiences using the technology

- learn how to navigate the challenges their students will face using the technology

- create systems on how to support them so students don’t fall through the cracks

When schools and school districts make the decision to implement hybrid learning, teachers have to:

- learn all of the above, and

- implement safety precautions in their classrooms

- teach their students how to follow these new rules

- create multiple ways to access the work AND themselves since they’ll be teaching half the time and unavailable to answer questions

- build a classroom culture that can exist beyond the classroom walls so students feel they can manage and be independent when they are at home alone

- practice their own self-care and wellness

Adapting as Part of the Job

Teachers have been adapting to the constantly changing climate of education since beginning their careers. The adaptations they’re making for learning in the time of COVID-19 might feel like just another change. In the decade that I’ve spent in various classrooms and schools, I’ve seen the effects of No Child Left Behind come and go, massive overhauls to standardized tests and standards, changes in curriculum, the launch of Race to the Top, and adoption of new frameworks, one after another. Educators who’ve been teaching for multiple decades have adapted their practice countless times, and to many, learning a new technology or a new way of teaching is just part of the job. However, the adaptations that teachers are making in the wake of COVID-19 have immediate implications for students, forcing us to ask the following key questions:

- Adaptations to Technology – Is the new technology accessible to all students? Even if it’s accessible, does the use of the technology support equitable learning? Is the use of this technology sustainable over the course of time?

- Adaptations to Student Expectations – Have student expectations changed or been lowered given the new learning environment? Are we equitably focusing on rigorous learning, despite the changes in how learning is delivered? Do these expectations maintain fairness and consistency across districts and geographic regions?

- Adaptations to Place – How has the learning environment shifted for students? What are the implications for learning (i.e., safety, privacy, accessibility)? What advantages and disadvantages are there to the new environment that students are learning in, such as easier or more difficult access to the outdoors, to the Internet, and to support?

In Support of Teachers and Students

Many of the “big” decisions discussed here, such as whether a school will move to virtual or in-person learning this fall, will continue to be made by non-classroom teachers. As these decisions are made, leaders can consider the following to support the adaptations that teachers will make to their practice and to ensure that students have equitable access to learning this fall.

- Technology – Is technology the norm or is it the tool?

- Understand that many teachers do not use technology as the foundation of their teaching practice. Their students learn from them through stories, years of experience, and connection to the world that lives outside of technology.

- Just like with students, access to technology, such as 1-1 devices, doesn’t always equate to effective use of that technology. Provide training so that teachers have opportunities to practice using the tools, and in turn, teach their students to better use them.

- Provide other options. If technology is a tool, then there are other tools available. Options will level the playing field for teachers and students.

- Expectations – Adjust, but don’t lower.

- Zaretta Hammond’s Ready for Rigor Framework emphasizes the importance of supporting students toward becoming independent learners, not just through cultural awareness, relationships, and building a strong community, but also setting high expectations and “creating opportunities to stimulate brain growth and intellective capacity” (Hammond, 2014). In a virtual or a hybrid environment, leaders should consider how they can support their teachers in building powerful learning experiences.

- A changed environment doesn’t mean changing the rules, but it does mean adapting them so that all students can experience the learning fully.

- Place – Encourage place-based learning experiences.

- The one commonality is that we all have a place. Whether a student is learning from inside their home with multiple siblings surrounding one computer, or the comfort of their bedroom with the door closed until the school day is over, there’s much they can learn from their “place.”

- Encourage teachers to adapt curriculum and learning experiences so students can safely connect with the outside world, beyond their computer screens.

- If students are engaged in virtual learning, one of the benefits is they now have “place” at their fingertips. What was once a lengthy process of paperwork and waivers to take a field trip outside of school grounds, is now accessible by older students independently.

- Place-based learning is not just nature-based education, but a focus on the culture, identity, and history of a place. Encourage teachers to use this physically distanced time to learn about the identity of the communities that they work in.

Years back, I worked at a school where the permitting for a new structure was delayed. Meanwhile, the school year went on and the students needed a classroom, whether the new structure could be built or not. That year, the “Tent” was born – a standing tent structure, held down by cinder blocks and crossed-fingers during big storms. Sometimes, when it was really sunny, the glare was too strong on Chromebook screens. On rainy days, the noise was too loud for direct instruction. The Internet didn’t always work in the Tent, and students had to constantly move their seats around to avoid getting their belongings wet. Classes in the Tent were indeed different, but they were still part of the landscape of learning. Teachers and students adapted, but it didn’t alter the expectations of what rigorous and powerful learning could look like. When I look back on the workshops from this summer, I remember the Tent. In some ways, we recreated the Tent classroom online, adjusting to the technology, learning new platforms and new content, and supporting each other when it didn’t always work out the way we thought it would. There’s no doubt that teachers are resilient and adaptable. Let’s remember that, but also show grace in making decisions on behalf of them – because their experiences directly connect to the accessibility that our students will have toward equitable and powerful learning this school year.

References

Hammond, Z. (2014). Culturally responsive teaching and the brain: Promoting authentic engagement and rigor among culturally and linguistically diverse students. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin.

Author Bio

Based in Homer, Alaska, Kay Sturm is currently the lead consultant on school and curriculum design projects with The Umi Project, an organization that focuses on the intentional design of student-centered learning. She is also a National Faculty trainer for PBLWorks. Kay spent her time as a classroom teacher and school-level leader in Hawaii and holds a Doctorate in Education with a focus on facilitating authentic project-based learning. She was named Charter School Teacher of the Year in the State of Hawaii in 2016, while working at a project-based, sustainability-focused middle school.