By. Maria Cuzzocrea Burke, Discovery Elementary School

“If a child is to keep alive his inborn sense of wonder, he needs the companionship of at least one adult who can share it, rediscovering with him the joy, excitement, and mystery of the world we live in.” ― Rachel Carson (Carson, 1965, p. 55)

When one thinks of the woods, images of dark, dense forests, the Big Bad Wolf, or other sinister fairy tales like Hansel and Gretel or Into the Woods might come to mind. For others, the woods evoke visions of transcendental forest bathing and quotes from Thoreau or Emerson – solitude, a meditative thru-hike, or a Walk in the Woods. As a child, the woods were a place where I could use my imagination, climb trees, design imaginary floor plans in open spaces between towering trees, or assemble makeshift forts from found materials in the garage – it was a place where I could explore, dream, wonder, and envision my future. I never imagined that my dreaming and scheming as a child would one day play out in the creation of an outdoor space at my school, Discovery Elementary School, in Arlington, Virginia.

Over the past two years, Discovery teachers have partnered with outside experts in design, architecture, and building to create a fifth-grade design challenge. Just one of these experts is Dina Sorensen, Senior Associate of DLR Group and formerly of VMDO. Dina was instrumental in furnishing the spaces at Discovery to epitomize the school’s learning potential. Using educational evidence-based research as inspiration, including Nancy Wells’ research on children’s nature-deficit disorder and the late Edith Ackermann’s play-based research, the design challenge is a semester-long educational mastery project built around a maker curriculum. Our team worked with art teachers, fifth-grade teachers, the math coach, the technology coach, and the gifted coach to capitalize on a variety of professional perspectives and expert inspiration, empathizing with and synthesizing new vantage points. The collective goal was for Discovery students to experience design thinking modes including empathy, research, defining the challenge, prototyping, creating, refining, and reflecting. We also wanted to find ways to embed the core curriculum into this project, such as measuring design dimensions to scale or incorporating marketing pitches into persuasive writing lessons. Through experiential learning, students would tailor their learning based on interests by volunteering for various roles.

Discovery’s second annual design challenge engaged 125 curious and highly motivated fifth-graders. For this challenge, we wanted students to envision a ‘forest classroom’ and then transform a wooded area adjacent to the school playfield into a place where students and teachers could engage in ‘expeditionary’ learning. Nature would serve as the ultimate inspiration for this design thinking challenge. Through our team’s research we learned that “… environment-based (or place-based) education can surely be one of the antidotes to [the] nature-deficit disorder. The basic idea is to use the surrounding community, including nature, as the preferred classroom” (Louv, 2008, p. 201). With this in mind, we kicked off our efforts to create the Discovery Woods.

First, we needed to settle on the ideal location. Once we identified a feasible site, we obtained approval from our administrators and facilities office and set about cleaning the space with our students and the school community. Next, students researched the space using empathy to guide their efforts. Installing a night vision camera allowed them to observe the site’s visitors, including deer, fox, and raccoons. They observed, collected, identified, and analyzed their living and nonliving findings. They then began to conceive of ways to design their ‘classroom’ while protecting the wood’s inhabitants.

The students’ research continued as they explored cradle to cradle methodologies and how designers use biomimicry and sustainable measures when creating new products. This research informed how they formulated their design’s specs —what materials would they use, how many would the space seat, how would the space be used, and how could it be repurposed later. Then, students researched ways their design could evolve while leaving a net-positive impact on their environment. Although not a native species, students found bamboo growing in the woods and were inspired to use the resources found in the space to create their forest classroom.

The final phase of research was inspired by risk-taking in nature. Through a presentation shared by Nancy Wells of Cornell University, students learned that our working memory, focus, and attention are activated in nature. According to Wells, “By bolstering children’s attention resources, green spaces may enable children to think more clearly and cope more effectively with life stress” (Louv, 2008, p. 105). Students practiced creating ephemeral seat designs and playing with natural materials. They identified perceived natural dangers in the woods including ticks, animals, and poison ivy. They learned to trust one another through physical risk-taking games such as trust falls. Deep empathy and research enabled students to define their ideas and visualize their designs.

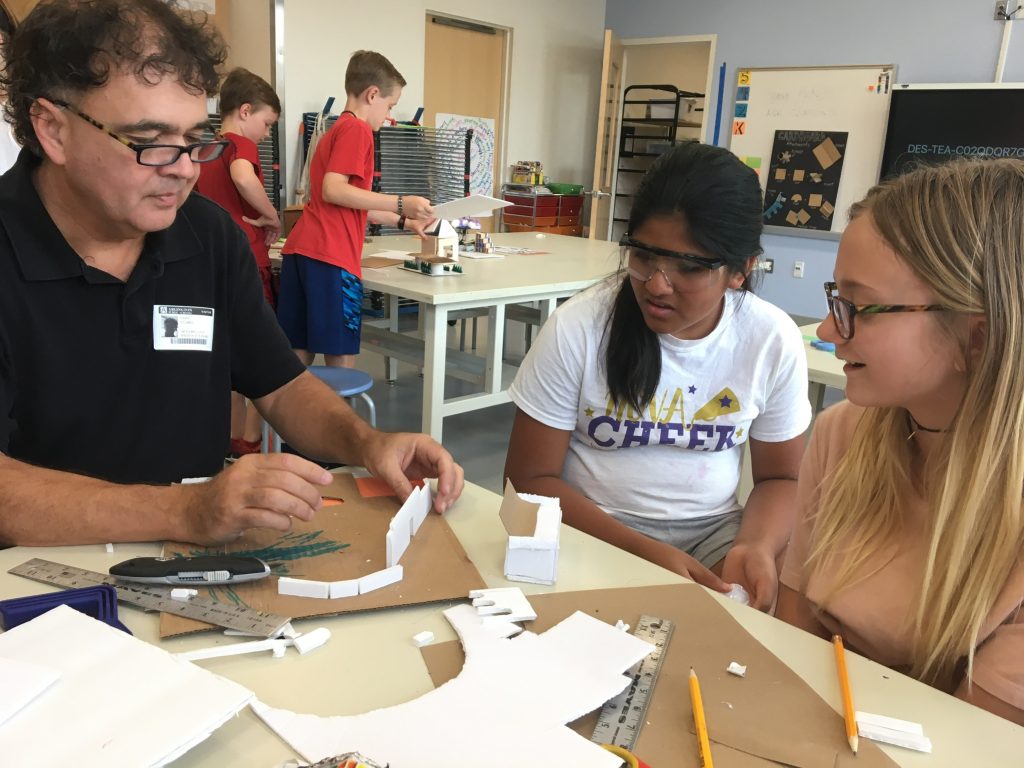

Following the research phase, students applied their understanding and collaboratively illustrated designs to the creation of their outdoor classroom spaces. Industrial Designer and Architect David Stubbs, founder of Culture-Shift, facilitated a two-day maker prototyping effort in the Art rooms. Here, students transformed their 2D sketches into 3D models. Working in teams or individually, they created prototypes using low-tech maker materials, hot glue, and, with the help of teachers, utility knives. A 3D printer was used to produce more robust models. During the prototyping phase, David stressed to students that “Failure is not a word.” Students reflected and refined their work with multiple iterations—living out David’s notion of failure. They composed persuasive pitches to their classmates and critiqued solutions to possible design problems.

Alex Gilliam, a building hero from Public Workshop, led the project’s building phase. With Alex’s creative guidance, students evaluated their designs and began to create and build using tools and materials that took risk-taking to another level. They painted, sawed, and drilled to bring their dream outdoor classroom to life. The final days and late evenings spent creating the classroom ended up building much more than a structure to sit upon. It built a community, as parents, students, and staff worked together to complete the space.

To culminate this learning expedition, a “map” was created to tell the story of this project and help others navigate this new space. A documentary team photographed, edited, and produced a visual story of the design challenge process. A graphic design team created promotional posters of the challenge to inform other students of this venture. Yet another design team worked with Iconograph experiential graphic design staff to create wayfinding signs to entice teachers and students to use the outdoor learning space and to educate them about the inhabitants found there. Once complete, the students claimed their territory by naming it “Nature’s Hideout.”

Bridgett Luther, Founder of Good Causes Corporation, and Michelle Amt, Director of Sustainability at VMDO (both formerly of Cradle to Cradle), along with Dina Sorensen facilitated the challenge’s culminating reflection. They asked us to think about the materials we use when designing and how to create using a circular economy. “What if humans designed products and systems that celebrate an abundance of human creativity, culture and productivity? That are so intelligent and safe, our species leaves an ecological footprint to delight in, not lament” (McDonough and Braungart, 2002, pp. 15 – 16)? Using an age appropriate analogy, Michelle Amt compared the earth to a backpack. “If someone borrowed your backpack, and they took something out of it, you’d hope that they would return it or replace it—just like we should with the Earth’s resources.” Students learned to design by mimicking nature and to think about the environmental effects of the materials we choose. Students contemplated the biggest challenges they faced and how they could improve upon them. They learned that unfinished work was just as valuable as completed work – they “learned by doing” through the entire design thinking process.

In mid-February 2019, the outdoor classroom’s wayfinding signage was installed using neon posts, beckoning teachers outside to “Nature’s Hideout.” First-grade, Art, and fifth-grade teams have started to bring their students out to gather and learn in this natural setting. Community support and involvement was vital to the success of this place-based challenge. Through commitments from design and sustainability partners, parents, students, and faculty, the Discovery Design Challenge fostered a hunger to tinker and make, an admiration for nature’s engineering, a longing to make a net-positive impact in our school, and a sense of wonder.

“I am a designer!” the Discovery fifth-graders cheered.

References

Carson, R. (1965). The Sense of Wonder. New York, NY: Harper Collins Publishing.

Louv, R. (2008). Last Child in the Woods: Saving Our Children from Nature-Deficit Disorder. Chapel Hill, NC: Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill.

McDonough, W. and Braungart, M. (2002). Cradle to Cradle. New York, NY: North Point Press.

Author Bio

Maria Cuzzocrea Burke teaches Art at Discovery Elementary School in Arlington Public Schools (Virginia), where she has also served as a County Mentor and Lead Art Teacher. She is the mother of an Appalachian Trail thru-hiker and an active member and presenter at the Virginia Art Education Association and National Art Education Association’s conferences.