By. Tracy Washington Enger and Mary Jo Errico, Ph.D.

Children spend much of their time in schools, which, on average, are more crowded than many other indoor spaces. In fact, schools often have four times the population density of a typical office, which can have a major impact on the indoor environment. Good indoor air quality (IAQ) is an important component of a healthy indoor environment in schools and can contribute to improving student health. However, schools face numerous challenges to maintaining good IAQ. Deferred preventive and regular maintenance, postponement of minor and capital repairs, and delays in major system and component replacements can result in costly issues, including those related to poor IAQ. These challenges, combined with limited budgets, can make managing indoor air in schools difficult and prolong the amount of time students, faculty, and staff are exposed to poor IAQ.

According to the 2017 Harvard School of Public Health report Schools for Health, more than 40 years of scientific research has led to many insights about how the indoor environment influences student health, well-being, and productivity. IAQ and other school building conditions such as ventilation, thermal comfort, lighting and views, and acoustics and noise play an important role in a student’s ability to focus, process new information, and feel engaged at school. These indoor environmental quality (IEQ) issues can lead to short- and long-term health problems, such as coughing, eye irritation, headaches, allergic reactions, and in some cases, life-threatening conditions. IEQ issues can also impact cognitive function and mental well-being, including attention, comprehension, annoyance, and irritability, and can affect long-term academic performance of students. Continue reading to learn how the physical environment, occupant health, and student and staff performance are interconnected.

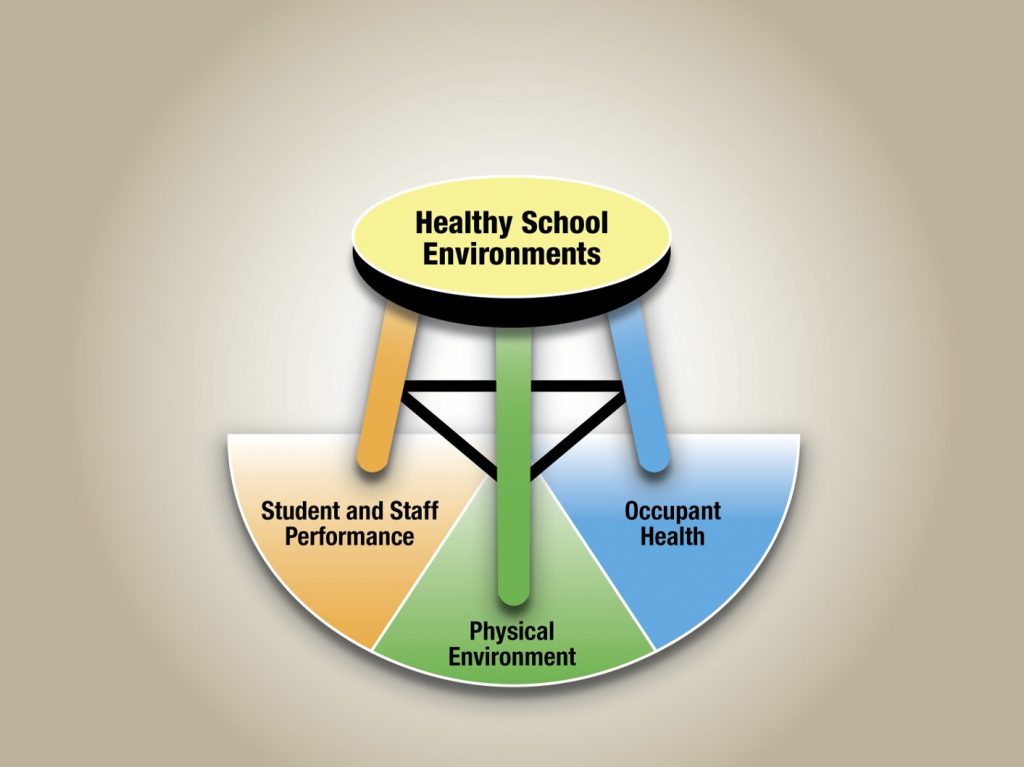

The Three-Legged Stool

It’s helpful to think of the benefits of IEQ management and healthy school environments as a three-legged stool. All three elements – the physical environment, occupant health, and student and staff performance – are equally important, and when combined, support a balanced and healthy school environment.

Physical Environment

Data from the National Center of Education Statistics indicate the average school building in the United States is 44 years old. One quarter of school buildings need extensive repair, and half of all schools are reported to have occupant complaints related to IAQ. The age of a building affects its physical environment, as older buildings are likely to need more frequent repairs. The physical environment of a building also determines the building’s mechanical systems and the methods used to maintain the building and its systems, such as the chemicals used for cleaning and pest control and the handling of pollutants. All these factors influence the quality of the indoor environment.

Occupant Health

Indoor air pollution, like outdoor air pollution, can negatively affect health if not properly addressed. In fact, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and its scientific advisory board consider poor IAQ to be one of the top five environmental threats to health. A host of pollutants, allergens, and asthma triggers may be found indoors, including mold, volatile organic compounds (VOCs), radon, lead, asbestos, pesticides, second-hand smoke from tobacco products, and more. Studies of human exposure to air pollutants conducted by EPA indicate indoor levels of pollutants may be two to five times – and occasionally more than 100 times – higher than outdoor levels. These levels of indoor air pollutants are of particular concern because most people spend about 90% of their time indoors. Additionally, children often are more susceptible to pollutants because they breathe proportionately more air than adults. The state of a school’s physical environment can significantly influence student health and exacerbate asthma, which is a major health concern in schools and can negatively affect student attendance. Nearly one-in-13 school-aged children has asthma, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reports that asthma is a leading cause of school absenteeism. In some states, school funding is tied to student attendance, and absenteeism caused by asthma can cost districts significant amounts of money. By improving IAQ and acting quickly if an IAQ issue arises, it’s possible to protect the health of students and staff, thereby saving the school district money.

Student and Staff Performance

Health directly relates to the ability to think, learn, and work. Studies have consistently shown that healthier indoor air helps students achieve higher test scores and helps both adults and children improve in their performance of mental tasks, such as concentration and recall. Schools for Health details how nine foundations of healthy buildings directly affect students’ thinking and performance. IAQ, ventilation, thermal health, lighting and views, moisture, dust and pests, noise, water quality, and safety and security have all been found to directly impact concentration, comprehension, attention, attendance, and performance on standardized tests.

The Critical Role of Preventive Maintenance

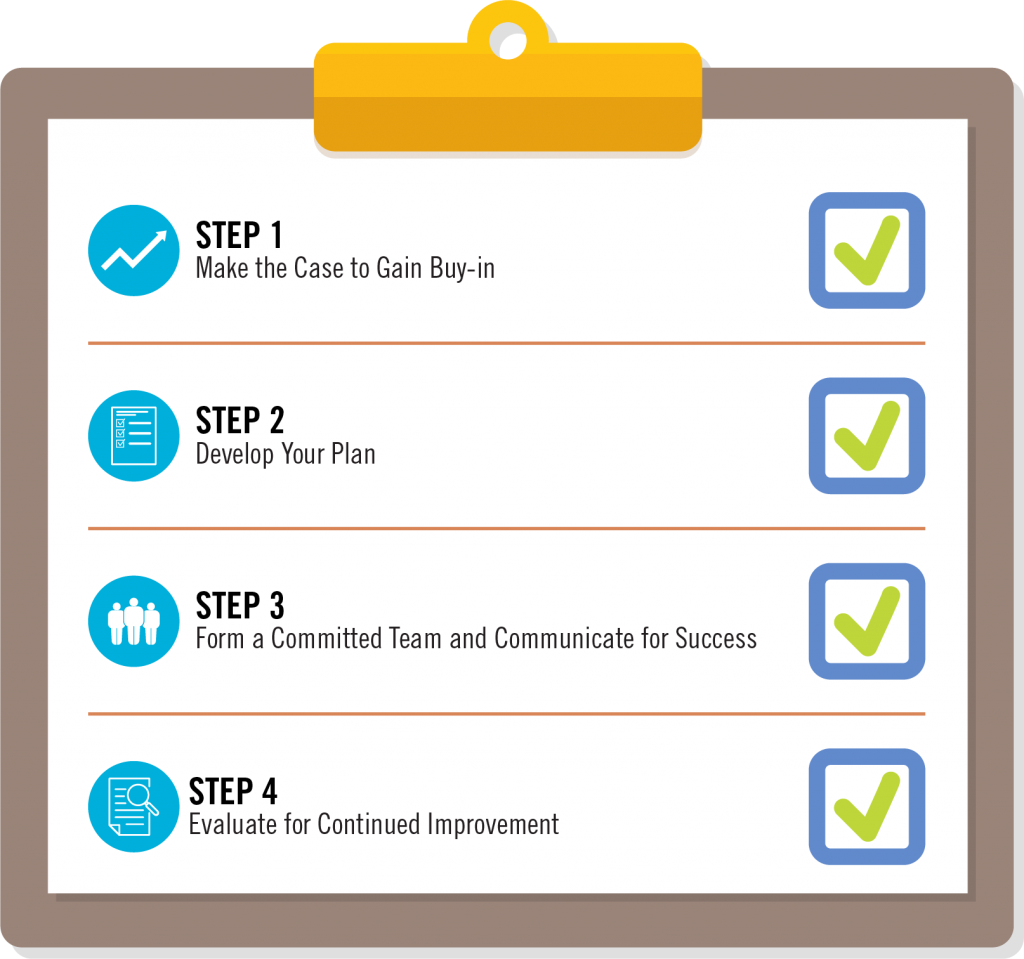

Schools can prevent IEQ issues from becoming costly problems through preventive maintenance. Saving money while keeping buildings safe and reliable is a top priority in most schools across the nation. EPA’s IAQ Tools for Schools: Preventive Maintenance Guidance and associated materials can help school districts take a holistic approach to preventive maintenance, IAQ management, and IEQ improvements. Including preventive maintenance as part of IAQ management in schools can result in opportunities to elevate current practices to become more proactive and predictive, achieve better facility performance, extend equipment longevity, and avoid costly repairs. By acting quickly to address IAQ issues as they arise, school districts can save money while protecting the health of students and staff. Sections of the guidance translate into four distinct and actionable steps that coordinate with EPA’s IAQ Tools for Schools Framework for Effective IAQ Management in Schools.

Step 1: Make the Case to Gain Buy-In

Making the case to various funders, decision-makers, and stakeholders is an important step to an IAQ management program’s effectiveness and longevity. By defining clear goals and objectives early on and utilizing financing tools mentioned in the guidance to make a solid business case for cost savings, schools can demonstrate that IAQ management is critical to the district’s mission and worth funding and supporting.

Step 2: Develop a Plan

Developing an IAQ preventive maintenance plan is the next step in achieving good IAQ. The guidance describes methods to track equipment inventory, conduct walkthroughs and assessments, maintain and service equipment, and manage processes and procedures effectively. EPA’s IAQ Preventive Maintenance Model Plan and IAQ Preventive Maintenance Checklist can be used as a starting point. There is also a mobile app that can support assessment efforts.

Step 3: Form a Committed Team and Communicate for Success

Building a committed team is critical for achieving success. The guidance outlines strategies for designating an IAQ Preventive Maintenance Coordinator, training staff, creating reports, and recognizing success. A committed interdisciplinary team of valued professionals is necessary every step of the way – from creation of the plan through its execution, review, and refinement.

Step 4: Evaluate for Continued Improvement

Continuous evaluation will help to ensure IAQ management practices are improving student health and performance. The guidance provides strategies for assessing a program’s success, as well as sample equipment inventory lists and tracking sheet templates to measure, analyze, document, and communicate results and success to others. Results can be used to refine goals and redirect investments to acquire needed resources.

Facility Resources and Solutions

Cleaner, safer, and healthier learning environments for students and staff are achievable through effective preventive maintenance. EPA has the resources necessary to train, educate, and support school districts and their staff on IEQ management. The IAQ Tools for Schools Action Kit, IAQ Tools for Schools: Preventive Maintenance Guidance, School IAQ Assessment Mobile App, Framework for Effective IAQ Management, IAQ Master Class and IAQ Knowledge-to-Action Professional Training Webinar Series, and Energy Savings Plus Health guide are all offered at no cost on EPA’s website. These resources work together seamlessly and are tailored to help coordinate school IAQ assessments and management programs. Effective IEQ management will not only transform the school’s physical environment, but will directly and positively impact student health, thinking, and performance.

Author Bios

Tracy Washington Enger is a Community Leadership Development Facilitator at the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, where she applies her passion for improving public health to creating safe, healthy, and pristine school indoor environments. Ms. Washington Enger works with communities around the country and internationally, facilitating events which generate action to address critical health and environmental issues. She received her B.S. and M.S. in Journalism from Ohio University in Athens, Ohio. After graduate school, Ms. Washington Enger joined the Peace Corps where she taught English literature and language in Sierra Leone, West Africa. She is an alumnus of the Newfield Network international coaching program. Ms Washington Enger currently resides in Alexandria, Virginia with her husband and two sons.

Mary Jo Errico, Ph.D. works as a Biologist for the Indoor Environments Division of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). She is focused on translating scientific research surrounding indoor air quality in schools into actionable steps and guidance for school districts across the country. Prior to EPA, she worked as a civilian Industrial Hygienist for the Department of the Navy, conducting occupational exposure assessments and indoor air quality sampling. She received a B.S. in Honors Chemistry from Georgetown University and a M.S. in Chemistry and Ph.D. in Environmental Chemistry from Florida International University.