By. Winnie Litten, Oak Park High School

I first fell in love with biomimicry while attending a county-wide science leadership meeting in February 2017. I was there in my capacity as science department chair at Oak Park High School in California’s Oak Park Unified School District. It was toward the end of the first session when Nathan Inouye, Ventura County Office of Education Science Coordinator, asked us to watch a short biomimicry video from Janine Benyus. Janine is known as the “Biologist-at-the-Design-Table” and is co-founder of Biomimicry 3.8, the world’s first bio-inspired consultancy. The video was just a few minutes long, but I was hooked and my motivational fire was lit. I was transfixed by the simplicity, practicality, beauty, and scientific reasoning that underlies biomimicry – using nature as inspiration to solve our human problems by mimicking the evolved and sustainable strategies of living organisms. I knew that I needed to develop and implement a curriculum that supported the ideals of biomimicry. I also knew that students would love it.

Getting Started

The first step I took, within minutes of watching the video, was to draft an email to Superintendent Dr. Tony Knight, District Director of Curriculum and Instruction Jay Greenlinger, my principal Kevin Buchanan, and my two biology colleagues. I first explained the concept of biomimicry to them and then shared some thoughts on how it could be incorporated into our curriculum at Oak Park High School. My email read in part:

“Just throwing this out there…possibilities…a senior capstone class perhaps or part of the Foundations course (or at the very least integrated as part of EP&Cs in Biology curriculum)? There are links to Common Core, NGSS, California Science Framework, and California’s Environmental Principles and Concepts (part of the California Science Framework that students will be assessed on) – which has an emphasis in outdoor experiences.”

I included a screenshot of a cool biomimicry phrase, three links that described and defined biomimicry, and a link to the curriculum I wanted to purchase. I wrote, “Long story short, would we be able to purchase this curriculum – apx $250? I have already signed up for free engineering curriculum from “asknature” site. Seems very exciting, relevant, and standards-based!” In that one email I involved all the critical stakeholders, I provided evidence that it would meet multiple district imperatives and expectations and could be used in multiple courses, and that I was passionate to make sure it was implemented. Jay Greenlinger responded five minutes later – “We can definitely do this.”

Implementation

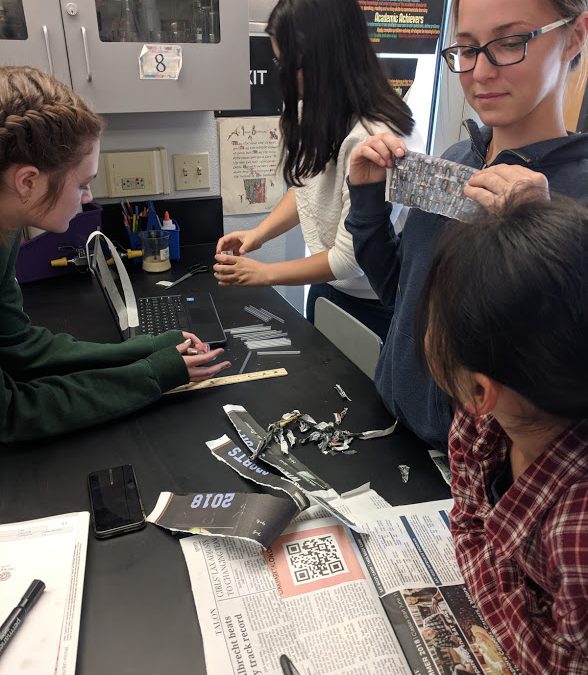

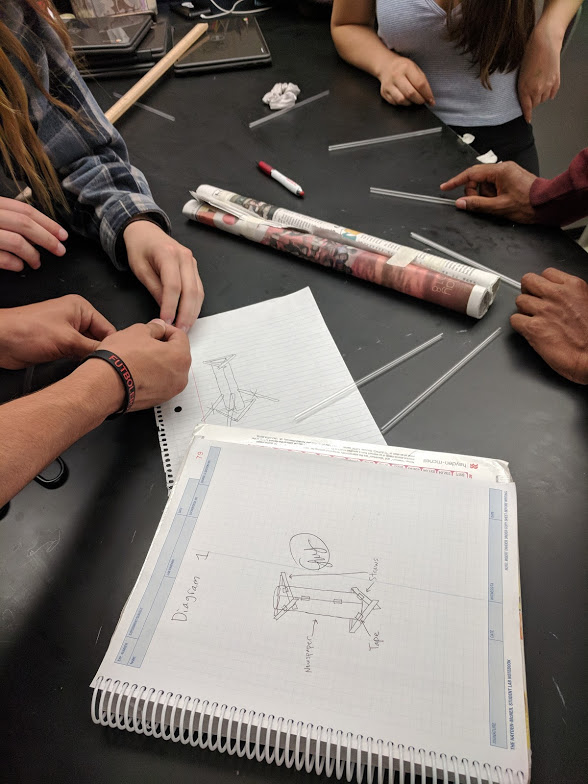

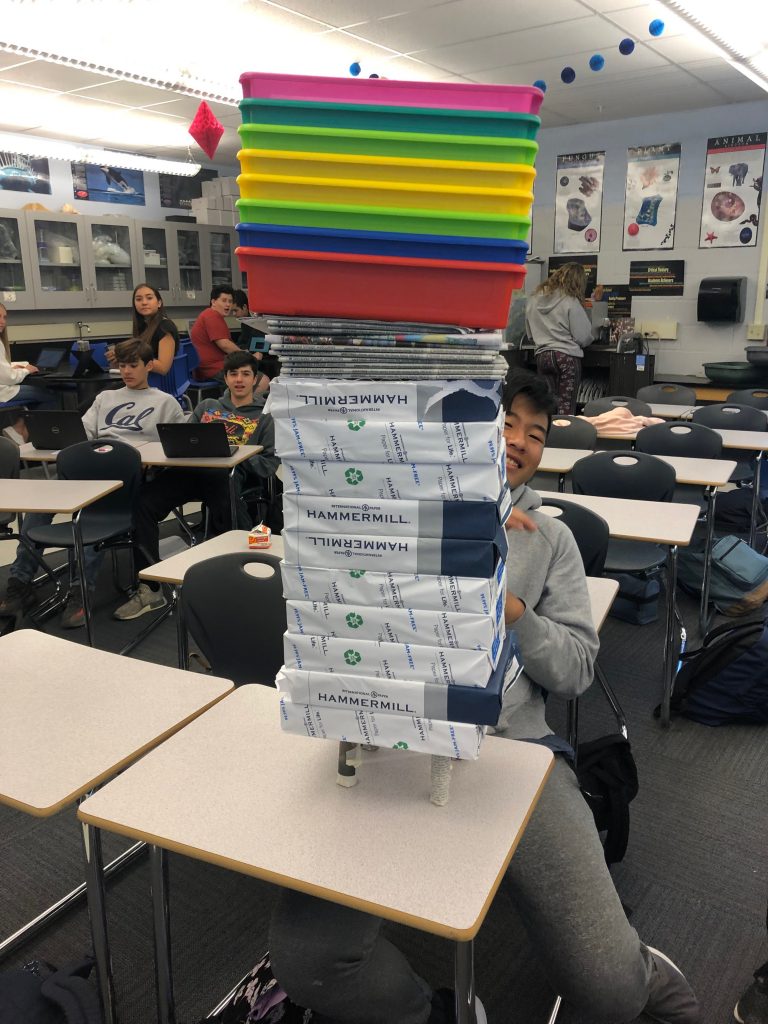

Next, I needed to start weaving biomimicry into the science curriculum. I teach three courses at Oak Park High School: Honors Biology, AP Biology (both of which are usually taken in tenth-grade), and Foundations of Science (a predominantly ninth-grade introductory course). The Foundations of Science course consists of two semesters, which can occur in any order: Earth & Physics and Earth & Chemistry. The intent of this course is to introduce students to the science practices and crosscutting concepts identified in the Next Generation Science Standards while incorporating technology. My colleague, Ellen Chevalier, and I developed the Earth & Physics semester from scratch. One of our key educational strategies involves using HyperDocs, a digital curricular pathway of instruction, collaboration, and interaction. Each HyperDoc is filled with current events and content focused on real-world applications. Ellen and I redesigned the course’s final capstone project so that students focus on the ideals of biomimicry. The project is called “Biomimicry – Inspirational Bones” and it’s an adaptation of resources from EcoRise. (EcoRise has given us permission to share this curriculum with other educators). Students start by analyzing the structure of the Eiffel Tower and learn that its design was inspired by femurs. The class then reviews the anatomy of compact bone so they can relate it to other architecture and building design. Next, students use newspaper, tape, and straws to build the lightest structure that can hold the most reams of paper. This involves designing, constructing, testing, and revising the structure. They realize that to succeed they need to mimic the structure of osteons, rings within rings of compact bone. They love it. This is a simple, practical application of the efficiency of those structures that have evolved over millions of years. As a final task, students examine companies that use biomimicry principles to inform their products and services. As a class, they look at a company called Bone Structure, whose aim is to build ‘net-zero’ energy homes. Then, students analyze other companies such as Sharklet Technologies, which makes a “skin” that mimics a shark’s micropatterns to inhibit bacteria from attaching, colonizing, and forming biofilms on things like hospital beds. Students are asked to identify:

- What problem is the company trying to solve?

- What is the inspiration for their product?

- How does their solution contribute to a sustainable future? Is it eco-friendly?

- How is this an example of biomimicry?

Students strengthen their understanding of biomimicry in AP and Honors Biology courses through the use of two guiding HyperDocs. The first HyperDoc reintroduces students to biomimicry through comparing and contrasting our “built world” to natural structures such as coral reefs or termite mounds. They look at the ways in which humans consume resources and pollute the environment using “heat, beat, and treat” strategies as opposed to recycling and upcycling strategies used by healthy ecosystems. Classes close the first HyperDoc by looking at several examples of biomimicry and attempting to see the world through the sustainable eyes of a biomimic. In the second HyperDoc, “Industry and Ecology, A Natural Fit” students learn about Industrial Ecology, which strives to:

- Reduce dependence on external resources (e.g., new materials and energy).

- Reduce or eliminate waste products, often by forming partnerships with other industries to increase the recycling of by-products.

- Ensure that interactions with natural ecosystems are limited and beneficial to all systems.

Students then study the dynamics of prairie ecosystems and apply this knowledge to city structures using the example of the industrial symbiosis project at Kalundborg, Denmark, whose Asnaes coal-fired electric power station is the center of a resource exchange system that includes an oil refinery, a plasterboard manufacturer, farmers, and municipal offices. Once again, students are able to appreciate the simplicity and wisdom of employing the sustainable practices of biomimicry.

We are just beginning to discuss and obtain buy-in to incorporate biomimicry into our third-year courses, Chemistry and upper-level Physics.

Growth Outside of Oak Park and Within

Once Ellen and I had introduced biomimicry into our curricula, we sought opportunities to present at conferences and share what we were doing in our classrooms at Oak Park High School with other educators. At each event we attend, we start our presentation with a “gallery walk” around a room where participants look at several images of biomimicry (backpacks, prosthetics, buildings, solar, cars, etc.) and pause at one they are most interested in. Participants try to identify the organism that inspired that product, and this starts the wheels turning. (The gallery walk is also a great way to introduce biomimicry to your students.) We then discuss what their ideas of biomimicry are and introduce them to the HyperDocs that we developed to use with our students. Biomimicry is a natural topic to discuss at science conferences; however, if we find ourselves presenting at a technology conference, we discuss our strategies for 1:1 technology in the classroom using our biomimicry curriculum as the example. The short-term view is that we are providing teachers with free resources and ideas to assist them in meeting their instructional goals. In the big picture, we are educating others about the sustainability practices surrounding biomimicry. This link provides access to all the information that we share during our presentations.

As Ellen and I were beginning to make the rounds at various conferences, our district administration was simultaneously pulling together a team to address these ideas districtwide. Our first “Biomimicry Cohort” meeting was held on June 13, 2018 and included approximately 10 teachers and administrators. At the meeting, we developed a Big idea of how Oak Park schools could promote sustainability of the environment. We asked ourselves three questions:

- What role will I have at home and school in promoting sustainability of the environment?

- What role will I have in our community in mitigating and restoring the environment?

- What role will I have as a global citizen in mitigating anthropogenic impacts and restoring and preserving the environment?

Our district is still developing K-12 curriculum that incorporates biomimicry principles, and our original cohort has become part of a district directive under the umbrella of sustainability. We now have stakeholder representation from students, parents, teachers, community members, and administrators.

Lessons Learned

I believe the reason Oak Park has been successful in developing and implementing its biomimicry curriculum is that we demonstrated to administrators from the start the ways in which teaching the tenets of biomimicry supports multiple goals, directives, and standards. If you are toying with the idea of incorporating biomimicry into your curriculum, a good place to start is to research your own district goals and see which can be supported. Within the Next Generation Science Standards you can identify LS2: Ecosystems: Interactions, Energy, and Dynamics, ESS3: Earth and Human Activity, and the engineering, technology, and applications of science and science practices while identifying various crosscutting concepts such as Cause and Effect, Systems and System Models, and Stability and Change. If you are in California, there are multiple connections with the state’s Environmental Principles & Concepts. Keep your administrators apprised of your development, use social media to advertise your students’ understandings and accomplishments, and be willing to revise your curriculum as needed.

Nobel Peace Prize winner Desmond Tutu said: “Do your little bit of good where you are; it’s those little bits of good put together that overwhelm the world.” You can start with your own “little bit of good” by introducing biomimicry to your students and plant the proverbial seeds of how to solve our problems using solutions inspired by all the evolved life that came before us. I encourage you to find your biomimicry path.

Author Bio

Winnie Litten is a science teacher, technology coach, and department chair at Oak Park High School. She is a leader for Ventura County’s Next Generation Science Standards implementation and has presented at local, state, and national levels on biomimicry, biotechnology, and authentic technology integration.