By. Skylar Primm, High Marq Environmental Charter School

I teach at High Marq Environmental Charter School in Montello, Wisconsin, an area surrounded by lakes and rivers. As an outdoor educator, I am quite used to adapting my practice to whatever Wisconsin’s weather brings. Typically, this involves actions like bringing adequate layers or changing plans on the fly when our school start is delayed. This year, the circumstances we faced were a bit more extreme.

Last September, the Montello School District took the unprecedented step of delaying the start of school by a full week due to catastrophic flooding in and around the city. Instead of welcoming new students and setting classroom expectations, teachers were helping fill sandbags and a Red Cross evacuation site was set up in our elementary gym. When school finally opened, buses were forced to take extended routes around our lakes to avoid a bridge that was not safe for heavy traffic. Many families were still living behind sandbags.

It was, in short, a very unusual way to start the school year. Nonetheless, we all pressed on and tried to provide as much normalcy as possible. High Marq’s curriculum is largely defined through student-driven, project-based learning, and all high school students are expected to complete a year-long capstone project that connects in some way to the theme of sustainability. This year, my students came up with some amazing environmental capstone projects. Some of them were inspired by the community’s experiences, and all of them were deeply meaningful to the student researchers.

Local Inspiration

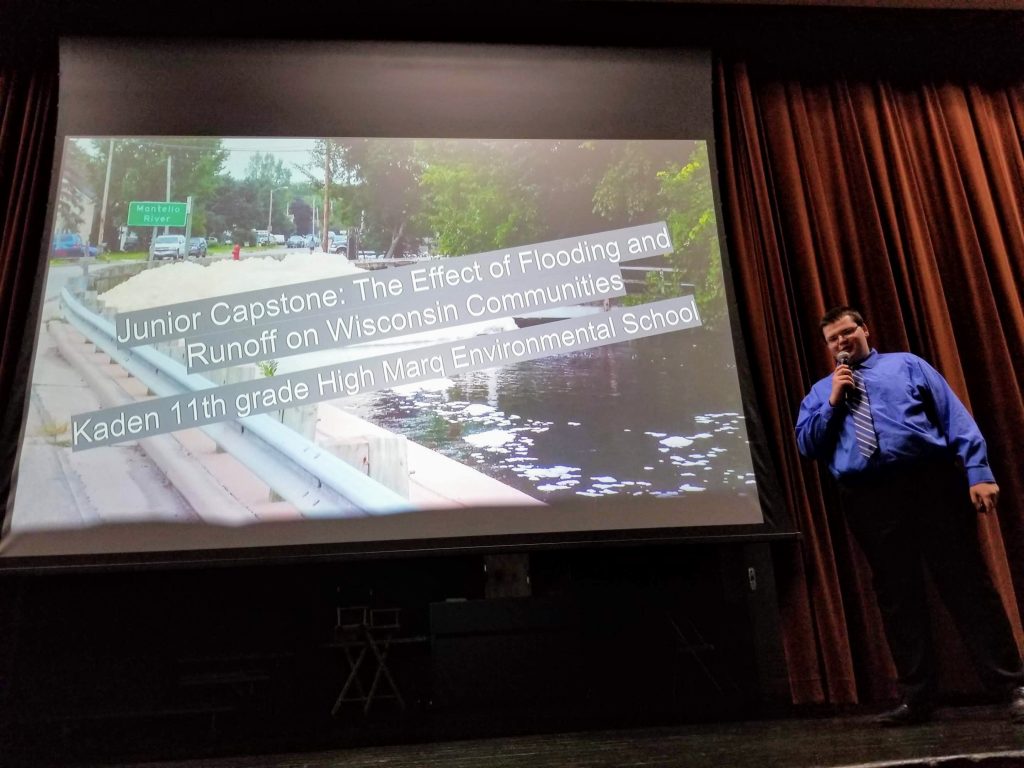

Kaden, who lives in a neighboring district along the Fox River that runs through Montello on its way to Green Bay, was inspired to explore the effect of flooding and runoff on Wisconsin communities, with the driving question, “What impact has the flooding in August had on our local community?” An avid fisherman, he observed first-hand both the impact of the recent floods and the ongoing problem of agricultural runoff in his local waterways and wished to learn more.

From this initial kernel, Kaden’s project grew to include an email interview with a local government official, an in-person interview with a long-time resident and naturalist, and research into Wisconsin’s major historical flooding events. He shared his work at a few public showcases throughout the school year and continued to revise it right up until the end. By the time he was finished, Kaden had demonstrated a thorough understanding of how phosphorus runoff impacts aquatic environments and what last year’s flooding looked like in context with historical events.

source: High Marq Environmental Charter School

Ultimately, the project held Kaden’s interest on a daily basis and throughout the year because of the personal connection he had to the material. In his end-of-project reflection, Kaden wrote, “I think I grew as a learner during this capstone because I was able to actually just sit down and research and read up on something for an extended amount of time!”

Mixing Social Studies and Science

While Kaden’s project focused directly on the local environment, other students took different research paths. Project-based learning lends itself very well to the interdisciplinary research required when learning about environmental issues and developing solutions to the complex problems involved therein. With that in mind, four of my students pursued projects that blended social studies and science in various combinations.

Nic struggled at first to come up with a topic this year, but he knew he wanted to learn about something big. He eventually settled on the Deepwater Horizon, an event that happened when he was very young and about which he knew very little. (Working with young people is great for reminding you that “historical” is relative!) Nic’s project was initially driven by the question, “How did the Deepwater Horizon spill affect the people around the Gulf of Mexico?”, but his focus shifted over the year to the human causes and environmental impacts. The thoroughness with which he can explain the disaster’s unfolding is striking. About the project, Nic wrote, “I hope that oil and drilling companies like BP and Transocean, respectively, have learned from these mistakes. I think that this is a perfect reference of what not to do when drilling for oil; drill fast, dangle incentives for meeting deadlines, and have executives who don’t know the first thing about oil tell rig workers how to do their jobs.”

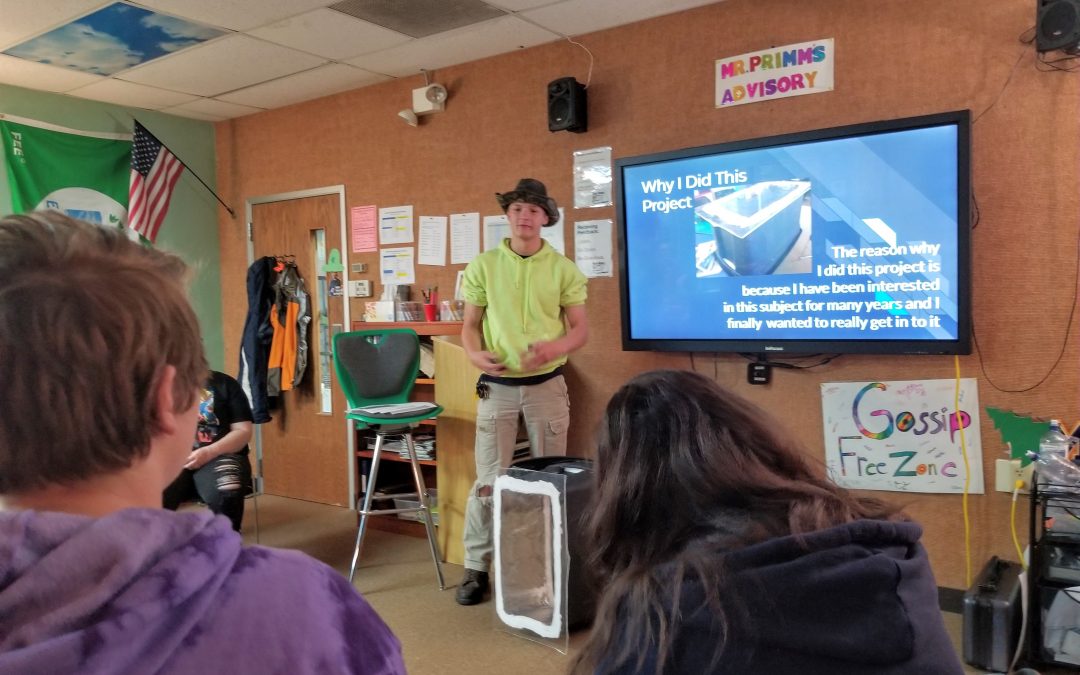

On the other hand, Elliott knew as early as the previous spring that he wanted to learn about zero waste lifestyles with a project cleverly titled Don’t Be Trashy and driven by the question, “How can we live more environmentally sustainable lives?” Elliott learned about best practices for waste reduction, sustainable food choices, and practical steps to lower one’s carbon footprint. One of the most powerful outcomes of his project was a zero waste support group led by Elliott that involved students and staff monitoring their waste for a week and sharing ideas for how to reduce it. Perhaps most importantly, they learned that a zero waste lifestyle is aspirational and perfection is not a realistic goal. As Elliott wrote in his reflection, “What I’ve been telling people in my presentations and one-on-one discussions is that just because you have the information to change the world, doesn’t mean it’s all on you, and it doesn’t mean you can’t make mistakes.”

source: High Marq Environmental Charter School

Similarly, David’s capstone was also designed to solve a practical problem—how he could fix a fresh, hot lunch on a construction job site. To that end, he got curious about solar ovens and the question, “What is the best design for a solar oven?” Through his research, David developed a clear understanding for the principles of solar heating, ultimately writing a cookbook of basic solar oven recipes and building his own solar oven out of materials he found at home. He tested it on a couple of school days with mixed results but intends to continue working with it this summer, writing: “Something I accomplished that I am really proud of is the solar oven that really did work. It takes a lot to keep it on track with the sun, but I was really happy with how the pizza tasted and I can’t wait to use this all summer.”

Finally, Abby’s capstone obliquely addressed the issues raised at the start of this article, with the driving question, “How can we as communities prepare for natural disasters before they cause too much harm?” Focusing on wildfires, earthquakes, hurricanes, and volcanoes, she researched the causes and effects of each, major historical examples, and even the benefits to nature that might arise from these “disasters.” Her project took a well-rounded approach to the issue, culminating in a clever, hand-drawn animation summarizing all that she learned about disaster preparation in an easy-to-digest format. As Abby put it in a reflection, “I found that being able to do something that I love while working on school assignments was a great thing. I noticed that it really made this project a lot less stressful.”

Conclusion

It is vital that we provide our students with opportunities to follow their passions and explore their world, particularly in times of uncertainty. These five capstone projects, representing over 350 hours of student learning time, are a small sample of the work my students have completed this year. Allowing students to pursue their individual interests within the broader contexts of sustainability and environmental education opens the door to deep, authentic learning and a sense of connection and rootedness that they simply would not have received from a traditional lesson or assigned project.

Author Bio

Skylar L. Primm has only taught in project-based schools. Since 2011, he has served as co-lead teacher at High Marq Environmental Charter School in Montello, Wisconsin, where students in grades 7-12 co-create their curriculum through project-based learning, weekly environmental field experiences, and student democracy. Skylar also works with the Greater Madison Writing Project, and in 2017 he was honored with a Herb Kohl Educational Foundation Fellowship. As of 2018, he serves on the board of the Wisconsin Association for Environmental Education. An erstwhile geologist, he much prefers teaching. He writes at medium.com/@skylarp.