By. Tom Harten

What do a cypress swamp, a historical museum, and the local landfill have in common? They all serve as field trip sites for students in the Calvert County Public Schools (CCPS) system. Through the CHESPAX environmental education program, students and teachers use these local resources and many others as venues for hands-on learning. Located on Maryland’s western shore of the Chesapeake Bay about 30 miles south of Washington, D.C., Calvert County is the state’s smallest county by area. Despite its small size, the county is home to a variety of museums, parks, and nature centers and two university biological laboratories that provide rich opportunities for learning about the natural world.

The name CHESPAX is a mash-up of the names of the two bodies of water that border this peninsular county, the Chesapeake Bay and the Patuxent River. CHESPAX operates through CCPS’s Department of Instruction, but the program’s success derives largely from partnerships formed with local natural and cultural resource agencies over the program’s 33-year history. Many of these agencies are charged with educating the public as a part of their organizational goals. Their affiliation with CCPS provides an opportunity for these organizations to fulfill their mission for public outreach and target their message to best meet student needs. The relationship with CCPS also helps district educators stay up-to-date with relevant educational practices and frameworks, such as the Next Generation Science Standards. According to Andy Brown, Senior Naturalist with the Calvert County Natural Resources Division (CCNRD), “The partnership between the Calvert County Natural Resources Division and CHESPAX dates to its inception in 1988. The ability to instruct CHESPAX lessons at CCNRD sites enables the division to further its mission of preserving the natural resources of Calvert County. Throughout this time, we have observed Calvert County Public School students develop a high level of environmental literacy and become stewards for our environment.”

CHESPAX field experiences are embedded within science and social studies instructional programs for students in grades K-8. Students develop content knowledge through classroom work prior to their field experiences. The trip provides an opportunity to apply their knowledge in an authentic setting, working alongside experts from partner agencies.

Each grade level completes a different unit with an accompanying field component. For example, fifth-grade students investigate the role of oysters in the Chesapeake Bay. In the classroom, students examine the history of the oysters’ decline in the bay, largely due to overharvesting and disease, and complete a variety of activities. One activity has students assume the role of citizens who hold differing perspectives on whether oysters are an economic or an environmental resource for the region. A field experience at a Chesapeake tributary engages students with measuring young oysters, collecting data on water quality, and investigating the organisms that inhabit an oyster reef community. The field program is taught by CCNRD educators with support from the Chesapeake Beach Oyster Cultivation Society, a local volunteer group.

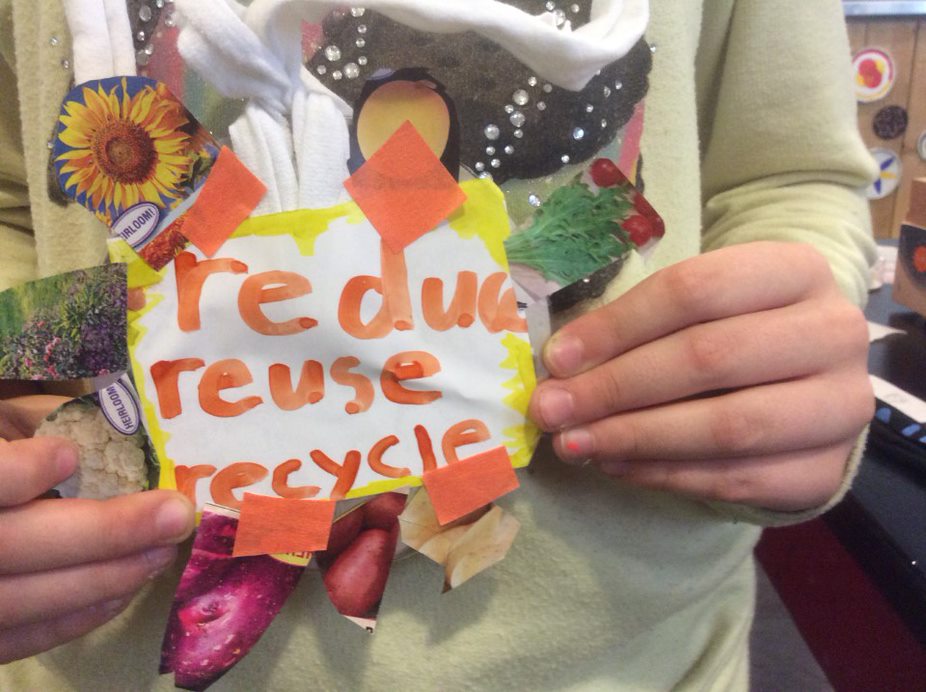

The proximity of the Chesapeake Bay, the Patuxent River, and surrounding natural areas makes it easy for CHESPAX to use these resources as living laboratories for nature-oriented field experiences. However, not all field trips involve a walk in the park. Second-grade students learn about natural resource conservation through a visit to the local landfill. After the classroom component, where students learn that virtually every product they use can be traced back to something that came from the Earth, they visit the local landfill to find out what happens to these items once they are thrown away. A trip to the recycling center helps them generate a list of items that can be recycled locally. Students are inspired to act when they visit the transfer station and witness the vast amount of potentially recyclable material being loaded up for a one-way trip to the landfill. Beach Elementary School teacher, Jenn Seibert shares, “The second-grade field trip designed and led by our staff at CHESPAX has certainly ignited the importance of caring for our environment among our students and their families. I have seen first-hand how this field trip experience motivates students to reduce, reuse, and recycle to prevent trash from having to go to our local landfill and preserve our natural resources. Whether it’s students reminding each other to bring a waste-free lunch to school or encouraging their parents to get a recycle bin for their homes, the message is heard, and students step up to make change. Students discover that by working together they can help to save our Earth, one community at a time.”

A second component of the second-grade field trip is a visit to the Annmarie Sculpture Garden and Arts Center, where students learn to craft a persuasive message using art as a medium and complete a creative reuse project to apply their skills. Following the field trip, students complete a community outreach project where they decorate re-usable grocery bags with persuasive messages about conserving natural resources. These bags are collected from each class and given to local grocery stores to distribute to the public on Earth Day.

CHESPAX programming isn’t just for younger students. High school students with an interest in the environment can join their school’s Envirothon team and work with partner agencies to learn about relevant natural resource conservation careers. Students work with professionals from agencies such as the local soil conservation district and forestry and wildlife organizations and explore techniques employed by professional scientists working in these occupations. They then use what they learn during a county-wide Envirothon competition. Winners advance to state and even national competitions.

CHESPAX also partners with the Prince Frederick Flyers UAS Team (student drone club) to conduct aerial surveys of wetlands in a local park. Students map out their mission plan prior to the visit and assume specific roles to collect and process the imagery with their drones in a safe and efficient manner. The resulting photographs and video clips are used to assess change within the ecosystem.

While most CHESPAX activities occur at off-site locations, the program also brings community partners to school campuses for on-site field experiences and to provide support for on-going classroom projects. For example, third-grade students raise hatchling diamondback terrapins as part of a “head-start” project through a partnership with Ohio University and the National Aquarium. The terrapins are released onto a Chesapeake Bay island after spending most of the school year in the classroom. Students learn about the terrapins’ habitat needs as well as natural and manmade threats to their survival. Classroom terrapins serve as Chesapeake Bay “ambassadors,” helping students form a personal connection to the species. Seventh-grade students raise native mosquitofish (Gambusia), which are made available to county residents interested in a natural mosquito control method. This project takes place in coordination with Calvert County’s mosquito control program.

The longevity of the CHESPAX program has yielded some enduring results. Middle school students have accrued roughly 25 years of data regarding the distribution of underwater grasses from a local creek. The data from the project is shared with the Virginia Institute of Marine Sciences (VIMS) and other agencies that are collecting bay-wide surveys of these plants. According to Bob Orth, a retired VIMS scientist, “Our monitoring of bay grasses is conducted with aerial photography at 13,000 feet. We are unable to identify specific species of underwater grasses. Having data from these students that tell us what species they find complements our data and provides critical information on population trends of different species. Their data set is unique for how long they have been conducting this work and we include their observations in our web-based reports available to the public.”

Costs for CHESPAX staff members (two teachers, an instructional assistant, and a secretary) come from the CCPS budget. Expenses for instructional materials, buses, and substitute teachers also are funded through the district. For most field experiences, partner organizations absorb the costs for naturalists and educators who provide the field programming. CHESPAX staff also seek out grant funding to support new initiatives or for specialized tools that are used during some of the field programs and projects.

CHESPAX staff also coordinate with local partners to provide professional development for district teachers. These sessions help teachers develop content knowledge and build confidence in teaching natural science to their students. Educators from partner agencies may also participate in training from CCPS staff to learn about new initiatives in the education field or about curricular changes that could impact the grade-level programs they teach as a part of the CHESPAX program.

CHESPAX staff work with program partners, classroom teachers, and building and district administration to develop a schedule for all CHESPAX programming. The centralization of this process ensures the necessary components for a successful trip are in place and relieves classroom teachers of the burden of organizing elements such as scheduling a bus, arranging for a substitute teacher, etc.

For generations of students who have passed through the CHESPAX program since the late 1980s, environmental education has been a constant thread running through their school experience. Today, parents attend field trips as chaperones at the very same places they visited as students. Classroom teachers who were raised in the county use their background to enrich environmental learning with their students. It’s common for CHESPAX staff to encounter former students at professional conferences and learn they were inspired to pursue a career in environmental conservation by those experiences during their grade-school years!

Many thanks to CHESPAX partner agencies: Calvert County Natural Resources Division, Calvert County Solid Waste Division, Annmarie Gardens and Arts Center, National Aquarium, Dr. Willem Rosenburg, Ohio University, Calvert Marine Museum, Prince Frederick Flyers UAS Team, Chesapeake Beach Oyster Cultivation Society, Jefferson Patterson Park and Museum, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Virginia Institute of Marine Sciences, Coastal Conservation Association Maryland, Patuxent Estuarine and Aquatic Research Laboratory (Morgan State University), Calvert Soil Conservation District, Calvert County Forestry Board, American Chestnut Land Trust, Calvert Mosquito Control Program, Friends of St. Clements Bay, St. Mary’s River Watershed Association

Author Bio

Tom Harten has been a teacher with Calvert County Public Schools’ CHESPAX program since 1992. Tom received his BS in Education at SUNY Cortland and his MA in Teaching from the University of Memphis. Prior to his tenure in Calvert County, Tom worked at environmental education centers in Georgia, New York, and Massachusetts. Tom is an avid birder and natural history enthusiast and has been able to apply many of these interests to instructional programming at CHESPAX. Tom has traveled to India and Japan as part of teacher exchange programs with those countries and spent a summer in Alaska’s Pribilof Islands as a PolarTREC teacher.