By. Phoebe Beierle

The novel coronavirus has disrupted business as usual across the globe, and the disruption of the K-12 education system is having ripple effects throughout the economy. School buildings were abruptly abandoned in mid-March as staff and students were required to remain at home and transition to a virtual teaching and learning environment. This left tens of thousands of school buildings closed with systems powered down or shut off to save energy and water. As school systems consider how to reopen for in-person instruction, leaders are turning their focus to the physical building, especially the health of the indoor environment.

Organizations studying COVID-19 and providing guidance on how to manage the disease, such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), World Health Organization, and ASHRAE, agree that properly operating ventilation systems, increased circulation of outdoor air, and improved filtration are important in reducing the risk of the virus spreading in buildings. Additionally, schools are developing plans that meet U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and CDC guidance around cleaning and disinfecting surfaces, including high touch points within the building, on buses, on playgrounds, and more. Air quality and the need for healthy, green operational policies and procedures in schools have never been more important. As the U.S. Green Building Council’s (USGBC) CEO, Mahesh Ramanujam, states in the organization’s new vision, “Unlike any other moment in [our history], this crisis will require us to fully re-imagine the spaces where we live, learn, work, and play.” Joseph Allen, assistant professor of exposure and assessment science at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health and director of the school’s Healthy Buildings Program, reflected this sentiment in his recent address at the U.S. Department of Energy’s Better Buildings Summit, saying, “Maybe for the first time in history, all of us recognize the primary importance that the built environment is having or playing on our health.” He added that, “We have many examples of where buildings prevent the spread of a disease. We’ve lost our way about what we know about keeping people healthy and safe and we need to return to that.”

Because of USGBC’s history in working with schools for two decades, we know the health of students and teachers is a stated priority of nearly every school system. We also know how health and sustainability can often be an afterthought when an institution is making decisions in a crisis. In anticipation of the hard choices and nationwide confusion that’s on the horizon, we started reaching out early to leading organizations that are working on indoor air quality (IAQ) guidance for schools, as well as the 200+ members of our School District Sustainability Leadership Network (SLN), many of whom are responsible for their district’s energy management, waste management, and healthy school programs.

National Guidance for Facilities and Health

In early May, the Center for Green Schools began a biweekly, informal email update to school health organizations and researchers, sharing what we heard about guidance in development around school facilities and health. As resources are finalized and become available, our plan is to add them to USGBC’s COVID-19 resource page. Currently, we are aware of separate, K-12-focused efforts led by several federal agencies, Healthy Schools Campaign, 21st Century School Fund and the National Council on School Facilities, Perkins + Will, Healthy Schools Network, the Collaborative for High Performance Schools, and the National Academies of Science. If you would like to receive email updates about the progress of this guidance, please write schools@usgbc.org to be added.

Survey

In early April, we surveyed SLN members, primarily from medium and large school districts across the U.S., to understand their response to COVID-19 and their top concerns about how the pandemic would impact their work. The survey was sent to approximately 235 individuals representing 165 schools or school districts. Forty-three complete responses were submitted, representing 36 school districts, 5,847 schools, and over 3.5 million students.

COVID Community Conversations

At the close of the survey, respondents told us they were interested in hearing from experts about best practices around sustainability and health, as well as holding “support group” calls to talk about the challenges they were facing. In response, we organized twelve different COVID Community Conversations on topics ranging from school gardens to green cleaning and energy management. Fifty school sustainability staff participated, many joining multiple calls.

Summarized below are some of the major challenges regarding IAQ and green cleaning brought up during these conversations.

Lack of Direction

At every level – federal, state, and local – folks are looking for guidance on what to expect in the coming months and how to proceed with school reopening. Since scientists are still working to understand exactly how to live with the virus safely, and budgeting is delayed, decision-makers have been hesitant to establish firm plans until they know more. It’s very challenging to proactively plan and advocate for best practices with so many unknowns.

Efficacy of Products and Technologies

Facilities departments are seeing an increase in sales pitches for air cleaning and purification systems, filtration medium, new cleaning products, and more. Without expertise or school-based case studies for these products and technologies, it’s difficult for facilities staff to navigate what will work and where, and what they should get in line to purchase.

Critically Limited Resources

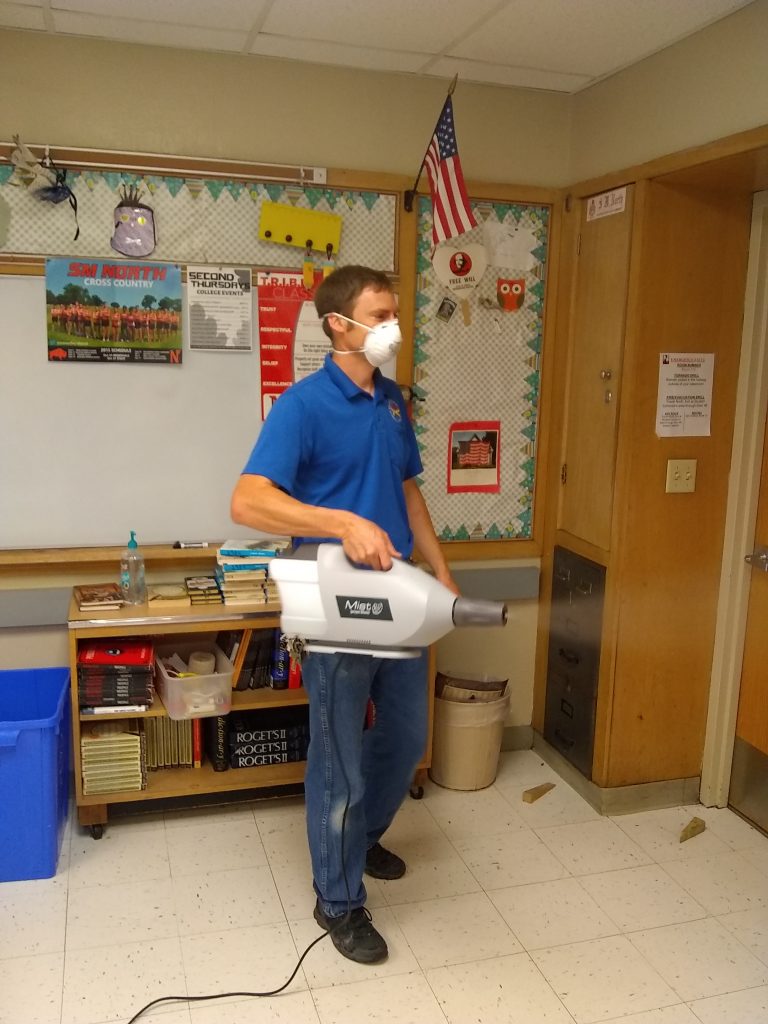

Organizations like ASHRAE are suggesting schools commission HVAC systems, upgrade to better filtration (MERV 13 or higher or HEPA), and clean more frequently and with more robust disinfection systems. Many of these recommendations are best practice in normal conditions but haven’t been implemented in schools due to lack of funding or staff capacity. Now, in a climate with budget deficits at the state and local levels, schools are scrambling to respond to meet these healthy school guidelines with even less money than they had before.

Conflicting Guidance

Guidance that is coming out from some states and localities conflicts with science or needs to be applied with regional climate considerations in mind. For example, the recommendation to increase the relative humidity in schools to 40 – 60% is just not feasible in a climate like Colorado’s. Additionally, much of the guidance doesn’t take into consideration district sustainability goals for green cleaning, reducing waste from packaging, and using less energy. Most school reopening guidance points to students eating meals in the classroom, which, for years, has been a challenge for sustainability staff who advocate for greener waste management, pest management, and cleaning practices.

Getting Building Occupants Onboard

Many sustainability and environmental health staff have always advocated for keeping clutter to a minimum and avoiding food in the classroom as ways to prevent pests and dust and promote good IAQ. While there may be an increased focus at this time on requiring building occupants to clean up and declutter their spaces to make it easier to keep schools clean, getting people to change habits long-term is hard. Sustainability staff raised concerns, based on past experience, about all that is being asked of building occupants.

At the Center for Green Schools, we know that we must act urgently to ensure schools and school districts have as much clarity as possible about how to keep students and teachers safe. We know that specific aspects of IAQ – such as the amount of CO2, VOCs, particulates, and humidity in the air – have demonstrable impacts on student learning, and on human health more generally (Baker and Bernstein, 2012; Eitland et al., 2017). For decades, USGBC has been advocating for healthy indoor environmental practices as part of the LEED rating system, Green Classroom Professional Certificate, and our public policy advocacy to call attention to the need to adequately and equitably fund school construction and maintenance. As students and teachers head back into school buildings over the coming school year, never has more been asked of the buildings themselves and of the men and women who operate them. The challenges are steep, and to meet them will require all the resources, creativity, and assistance possible – our families, communities, and economy depend on it.

References

Baker, L. and Bernstein, H. (2012). The impact of school buildings on student health and performance. McGraw-Hill Research Foundation and The Center for Green Schools. Retrieved from: http://www.centerforgreenschools.org/sites/default/files/resource-files/McGrawHill_ImpactOnHealth.pdf

Eitland, E., Klingensmith, L., MacNaughton, P., Laurent, J., Spengler, J., Bernstein, A., and Allen, J. (2017). Schools for health: Foundations for student success. Harvard T.H Chan School of Public Health. Retrieved from: https://forhealth.org/Harvard.Schools_For_Health.Foundations_for_Student_Success.pdf

Author Bio

Phoebe Beierle is the School District Sustainability Manager with the Center for Green Schools at the U.S. Green Building Council. She supports the Center’s mission by providing resources, tools, and research to a growing number of sustainability staff at school districts across the country. Phoebe comes to the Center from Boston Public Schools where she managed sustainability programs out of the district’s facilities department for five years. In past roles, her work has influenced Massachusetts school construction policy, resulting in statewide green building standards and millions of dollars in reduced operating expenses for communities across the Commonwealth.