By. Shannon Oliver and Justin Price

Between July 31 and mid-November 2020, the Pine Gulch Fire, the Cameron Peak Fire, and the East Troublesome Fire consumed 541,732 acres of grassland and forest in Colorado. Individually, they are the three largest fires in state history. Over the course of several months, these fires have transformed the landscape of an area slightly smaller than the state of Rhode Island. They have destroyed wildlife habit, contaminated the air for more than four million people living along the north-central Front Range, and will negatively impact the water quality of the Colorado River, which serves some 30 million people downstream. While many will call for forest management reform, it can’t be ignored that the entirety of the state is experiencing some level of drought, with many of the areas where these fires occurred falling in the Extreme or Exceptional Drought category.

Droughts have obvious impacts on a region’s natural ecology and can influence the severity of wildfires, much like those Colorado is currently experiencing. They also have an effect on people, their lifestyles, and the economy. As Colorado’s population increased over the past 20 years, so too did water use. These trends are not expected to change in the coming years. Just as Colorado’s population is projected to roughly double by 2050 from 2008 levels, water use is also projected to increase 50 – 75% over the same period. In fact, the 2015 Colorado Water Plan projected a 390,000 acre-feet/year gap between supply and demand by 2050, a roughly 22% shortfall in water need.

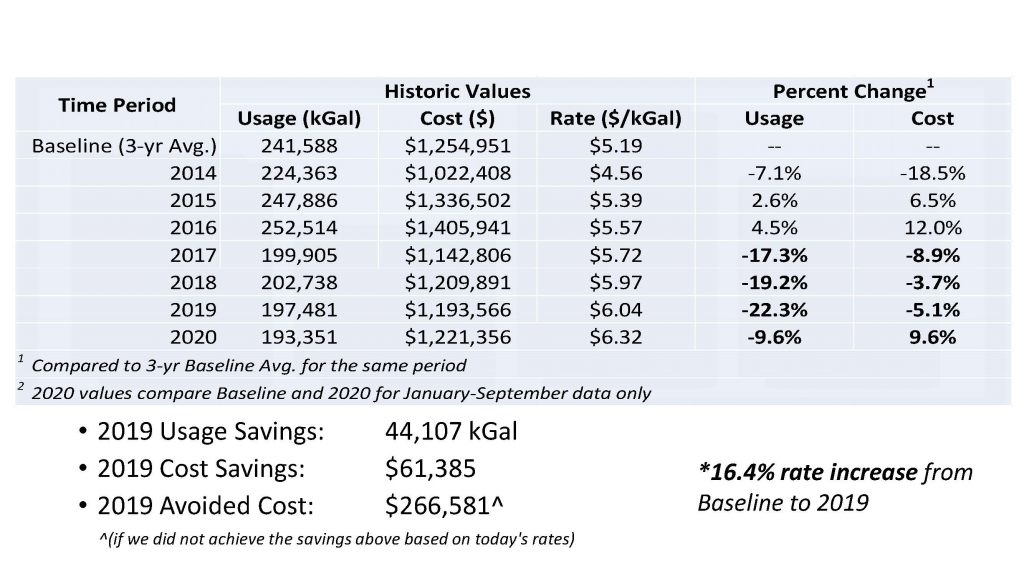

As a public school district serving roughly 37,000 students and 4,700 employees, Adams 12 Five Star Schools has seen water costs move into second place on its utility budget, with only electricity being a more costly line item. The district comprises 5.2 million square feet of building space and covers just under 60 square miles in the north-metro Denver area of Colorado. Of this acreage, roughly 475 acres are irrigated landscapes that comprise 80 – 90% of districtwide water usage. When the district’s sustainability department began setting utility and sustainability baselines in 2016, the team noticed an alarming trend: water costs had jumped from $1 million in 2014 to $1.4 million in 2016, a 40% increase. Reviewing water usage for that time period, it was noted that usage had only increased 13%. Digging deeper revealed that water rates ($/kGal) had increased more 22% over those same three calendar years. With local water providers announcing further rate increases in the coming years to address projected shortages in supply, it was clear irrigation water management was needed to protect our environmental and economic resources.

Utilizing trend data from 2014 – 2016, it was projected that a $1.9 million water budget request would be needed for 2017 if our irrigation practices weren’t adjusted. Historically, irrigation systems have been managed by the landscape team within the maintenance department. At the time, the district was sectored up with three irrigation technicians managing physical and virtual systems for their locations. The result was inconsistent irrigation programming and clock management, based on the particular irrigation technician’s level of experience. Working with the maintenance department, a new position was developed to support the irrigation technicians and act as a single point of contact for irrigation programming and clock management needs. Based on the knowledge of the maintenance manager, a 10% reduction in water use was a very realistic goal for a new role, which would easily cover a new FTE. Thus, the Water Resource Specialist role was born, with work commencing in January 2017.

Beginning with start-up in spring of 2017, one of the first activities the Water Resource Specialist focused on was updating the central irrigation control system. The latest version allows the system to incorporate zip code-based evapotranspiration rates into pre-programmed run times for each location. Other efforts included updating clock hardware where needed, ensuring adequate communication between individual clocks and central irrigation, incorporating weather center data for utilization of the rain shutdown feature, and communicating daily with irrigation and mowing staff to ensure no water waste was occurring while providing adequate water volumes to playfields and other high use areas. Success was immediately apparent when reviewing 2017 water use and cost data and continued through the current water season. These data can be seen in the table and chart below, with over 17% usage reductions and documented cost reductions through the 2019 calendar year. Data for 2020 is current through September and demonstrates challenges in usage tied to an incredibly dry summer, as well as the impact of costs tied to rate increases.

Of paramount importance in considering the success of this work is avoided cost. The gross cost savings detailed in the table and chart above are excellent wins to share with our community; however, you can’t ignore the costs the district would be paying had our baseline usage stayed unchanged while our rates increased. By that metric, the Water Resource Specialist role has avoided nearly $615,000 in unnecessary water costs.

Lessons Learned

While it’s clear the Water Resource Specialist role has helped reduce water consumption and stabilize water costs, developing this role hasn’t come without some hiccups and key lessons learned. For districts looking to follow suit, the first and most important thing to do is set a baseline and conduct a water cost analysis. As many energy managers tout, you can’t manage what you don’t measure. When completing this analysis, it’s important to consider what the intent of a new or reassigned FTE will be and ensure that role aligns with projected savings. During our baseline analysis and role proposal to district leadership, we included line item costs such as indoor water costs, stormwater fees, and sewage costs. These are important items to track, but ultimately they won’t be impacted by the Water Resource Specialist role as it’s structured for Adams 12 Five Star Schools.

Another important piece to consider is who will be involved in developing a role of this nature. Obviously, grounds or landscape personnel and those in maintenance or operations leadership positions should be included. They will have the insight to know how to structure the new position, or if a new position is the best first step. Adams 12 Five Star Schools already had a fairly extensive and robust irrigation control system in place; it just needed direct management and oversight from an experienced individual. Other districts may not have an extensive (or any) system in place, and a good starting point for them may be to get the hardware and software necessary to manage irrigation from a central location.

Finally, think about the reporting hierarchy of your district, how this role will be funded, and any external resources that will be needed to ensure success. In the case of Adams 12 Five Star Schools, the Water Resource Specialist role was initially funded through the utility budget, which is managed by the sustainability department, and reported to the maintenance manager. This structure ultimately created a divide between the Water Resource Specialist and the irrigation technician and mowers in the field. A perception developed that the Water Resource Specialist was not “part” of the maintenance team due to the reporting hierarchy and the goal of the role to find water waste problems. This can be addressed by considering the existing culture and ensuring that all team members impacted by or expected to work with a new role have a common understanding of the expectations for that role, as well as expectations for their position.

Perhaps the largest hurdles to overcome in managing water waste are the cultural norm that landscapes should be verdant green throughout the entire growing season, and the history of designing and installing easy-to-maintain, but often water-thirsty, landscapes. As our operations team planted more native species and embraced a ‘browner’ appearance during the hottest part of the year when school isn’t in session, our community was quick to let us know that our landscapes were unappealing in appearance. Thus, a stronger outreach component is needed when making operational changes that can be directly seen by the community. As water scarcity in our region has become a more concrete reality, the municipalities in which we operate have started transitioning to more water-wise landscapes and higher rates to motivate their (and ultimately our) community members to consider and appreciate a less water intensive landscape. There are ample opportunities to partner on pilot projects, test plots, and communication efforts with your water providers and some municipalities are starting to offer rebates for converting higher water use turf to more native landscapes.

As the Water Resource Specialist role evolves at Adams 12 Five Star Schools and resources shift, so too will the focus and activities of this position. New technologies continue to emerge in the realm of smart water management. Whether at the utility meter, within the irrigation clock, or out on individual watering zones, data are becoming more readily available to manage water use for landscapes. As the “low hanging fruit” of managing the system we have dry up, a move to landscape conversion will facilitate further reductions in unnecessary water use. While many playfields and sports fields will continue to need hardier and higher water use turf varieties, areas that lie dormant for most of the summer and low traffic areas intended as beautification landscapes can become much more water conscious. Finally, and perhaps most importantly, a future goal is to foster internal culture change around what Adams 12 Five Star Schools’ landscapes should and could look like. Current staff are well versed in the water and maintenance needs of Kentucky Bluegrass and other common turf types but are less familiar with maintaining native grasses that can quickly look unruly if not tended to properly. Ultimately, we all have a part in reducing water use in an area classified as high desert with a growing population. If we want to have adequate water resources for agriculture and maintain some level of green space in this arid environment for future generations, it’s crucial for behaviors and management practices to change, starting today.

Author Bios

Shannon Oliver has a BS degree in Environmental Health from Colorado State University and a Master of Public Health degree in Global Environmental Health from Emory University. His professional experience includes eight years of environmental and regulatory compliance for the oil and gas industry and nearly five years as an Energy and Sustainability Manager in the K-12 sector in Colorado. Recent focus of Shannon’s work has included student engagement on energy conservation and waste reduction, as well as district-level water use reduction efforts.

Justin Price is the Water Resource Specialist at Adams 12 Five Star Schools. He has prior grounds experience with several school districts and cities, served with the U.S. Navy and on the grounds crew at Camp David, and has architectural, engineering, and landscape design experience. Justin’s focus is managing one of Colorado’s most precious resources by ensuring the district’s irrigation systems are watering adequately while moving toward more sustainable and low-water use landscapes.