By. Jennifer Crandall

Sometimes the best things are right in your own backyard.

I took over the Family and Consumer Science position at Mount Desert Island High School in Bar Harbor, Maine a few years ago after spending 20 years teaching in alternative education. My principal is committed to improving the health and well-being of our high school community and asked me to grow the program. While many of our district’s elementary schools have greenhouses or school gardens, the growing season occurs mostly when school isn’t in session, so focusing an entire course on growing our own food seemed impractical. Instead, I decided to focus on accessing healthy food that can be grown or harvested right in our region.

Maine is a state of two halves: the northern part of the state is quite rural and has loamy soil that’s perfect for farming. The short growing season means that cold-hardy vegetables like potatoes and broccoli do best. In the southern and coastal parts of the state, retreating glaciers left a rocky soil that’s difficult to till. Here, there’s more of a “living off the fat of the land” ethic. Blueberries grow wild in abundance and are coaxed along by burning back the undergrowth that attempts to creep in. Cranberries and fiddleheads grow along the creeks and in the bogs and are harvested and sold on the side of the road by enterprising folks. And of course lobsters, mussels, and clams are harvested from the sea. It is a world of wild plenty. Along with the wild catch, lots of seafood is being grown in aquaculture facilities. Seaweed is another wild food that’s being harvested responsibly and farmed as well.

This agricultural abundance inspired me to develop a class called Farm to Table, which I teach to a mix of ninth- through twelfth-graders. The goal of the course is to give students a sense of what foods are locally available to them, who grows and harvests them, and what those foods taste like. The more locally sourced foods they consume, the more money stays in their community and the smaller their impact is on the environment. The class takes field trips to local farms, learns about their farming methods, and brings back samples of their products to cook in my teaching kitchen. We even plant some greens, radishes, and garlic in raised beds in the school courtyard.

Only 10% of the food consumed in Maine is grown or harvested here, so showing students what they have access to locally, and promoting those sources, is really important to me. Most of our food comes from 2,000 miles away and has a huge carbon footprint. It’s so important for my students to understand that they can get much of their food right here. Many of them have no idea. Last year, one my students was thrilled to see how broccoli grows as she had never seen it in the field before. Students beam with pride when they pull a radish out of the ground that they planted just a few weeks earlier, or when they pull a casserole out of the oven and everyone says it smells so good. Many of my students join the class with few, if any, cooking skills. Many have busy lives outside of school and don’t enjoy sit-down meals at home very often. Fast food, take-out, and grab-n-go meals are the staples of a busy teenager’s life. Giving them the time and tools to cook and eat healthy food fresh from the farm is a wonderful benefit of my job. My favorite is when a student asks me for a copy of a recipe because they want to make it for their family. They learn that what they eat impacts their community and their world. As one student wrote, “I think it’s important to be aware of and know the whole process of how produce gets from the farms to our kitchen tables, and the waste and expenses, so you can buy produce that will have less of an impact.”

There are a number of experiences my students look forward to each year in my Farm to Table class. There’s the cooking aspect, of course, but just as important are the field trips and communal experiences we have with farmers, producers, and the school community. In a normal year, my students would visit a mussel aquaculture operation and then cook with their product. We would enjoy guest speakers like the outreach coordinator of Maine Coast Sea Vegetables, who would bring their Kelp Crunch and other seaweed products for students to try. We would glean imperfect carrots at a vegetable farm to contribute to the Downeast Gleaning Initiative’s efforts to stock food pantries with fresh vegetables. We would’ve ended the term with a feast of all the foods we grew and purchased, sharing with others in the building.

However, COVID-19 necessitated I take a different approach to Farm to Table for the 2020 – 2021 academic year. For starters, I implemented extra precautions: students worked in small teams of two or three; wore masks, gloves, and aprons; and packed their creations in to-go containers to take home and eat. We opened the windows for more ventilation and sanitized surfaces before and after cooking. We learned to be flexible and change plans at a moment’s notice. Many farms and facilities weren’t able to host us because of their need for caution.

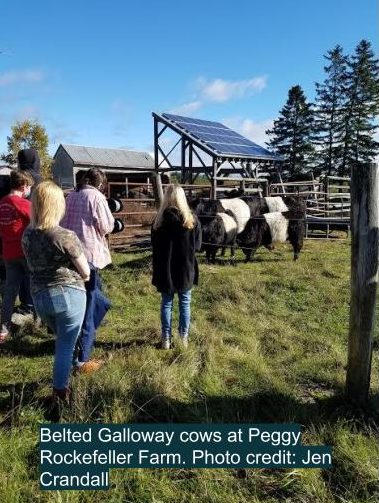

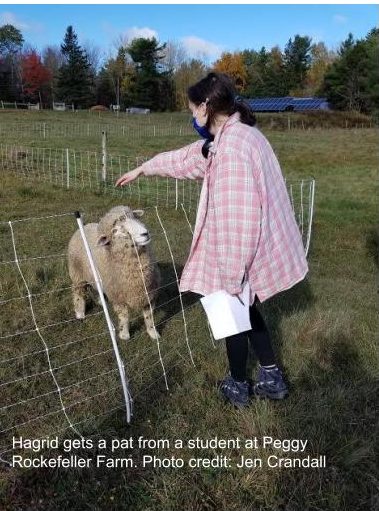

Despite these changes and limitations, we were able to make the best of the situation. We hiked to a bog on campus to pick wild cranberries and then baked muffins and scones. We visited an organic vegetable farm to help gather seaweed at the shore for mulch for their garlic beds. A guest speaker joined our class via Google Meet to talk with students about food insecurity and food waste in our region and what solutions are available. And we cooked some tasty dishes! Some of my students’ favorites were creamy cauliflower soup, roasted Brussel sprouts, and spring rolls made with organically grown vegetables from Bar Harbor Farm. Meat and eggs from Peggy Rockefeller Farm inspired students to make quiches, lamb meatballs, and vegetable beef soup.

One thing we learned as class was that COVID-19 had an interesting impact on our local food system. More people were interested in knowing where their food comes from and were frequenting farmers’ markets, CSAs (community supported agriculture), and the Farm Drop website to support our local food economy. While grocery stores struggled to keep their shelves stocked, farmers were working hard to keep up with demand. But as C.J. Walke, Farm Manager at Peggy Rockefeller Farm, told us, working faster to keep up with demand didn’t ensure more product. It just meant the animals they butchered for meat were sold faster. Once they were gone, there was no more until next year.

We may never get back to the way things used to be. We’ve learned that some of the new ways work better. Even as life returns to something a little more familiar, my students have a new understanding of what foods are available in their community and what they can grow themselves. They also appreciate that farm-fresh food tastes much better than food that has been trucked 2,000 miles to get to them. I hope they will carry those lessons with them as they become more independent and in control of what foods they buy, cook, and consume.

Author Bio

Jennifer Crandall is a Family and Consumer Science teacher at Mount Desert Island High School in Bar Harbor, Maine. She believes students learn best by doing and knows that access to healthy food doesn’t go very far without some basic cooking skills. A graduate of the College of the Atlantic, Jennifer approaches all her courses from the perspective of a human ecologist.