By. Kristen Mueller, Director of Communications, Earth Force

With a focus on engaging youth as environmental citizens, international nonprofit Earth Force is constantly looking for ways to encourage young people to improve the environment and their communities, now and in the future. One such effort is the Caring for Our Watersheds (CFW) competition, funded by agricultural company Agrium, which has been held in Northern Virginia and the Washington DC area (Metro-DC) for the past six years. CFW challenges participants to answer the question “what can I do to improve my watershed?” Students investigate their local watershed, identify pressing environmental issues, and develop an innovative and sustainable solution. They submit formal proposals detailing their project for a chance to win $10,000 in cash prizes. The program empowers students to imagine, develop, and create solutions in their local watersheds, while honing problem-solving, budgeting, community involvement, and presentation skills.

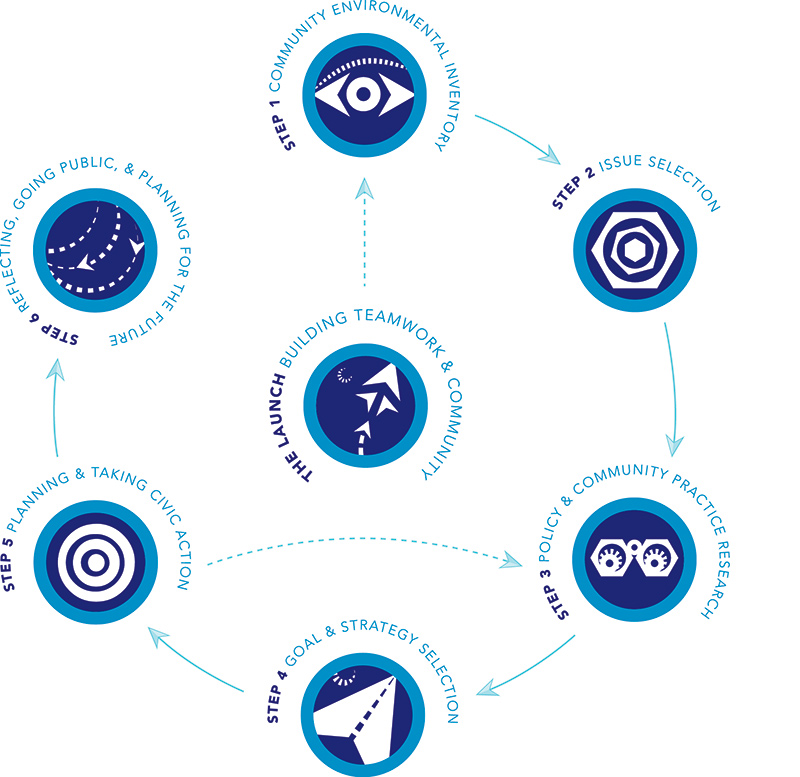

The cornerstone of CFW is inquiry-based learning, using the Community Action and Problem-Solving Process, a six-step model that combines the best of civic engagement, environmental education, and STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics). Using this model, youth are challenged to bring forth environmental issues that they care about in their local watershed. They then work together to design and implement a project that explores root causes and addresses a policy or practice related to the environmental issue that they identified in their community. The process’s focus on civic engagement helps learners become active participants in their communities by conducting balanced research, building strong community partnerships, and making decisions as a democratic group.

Earth Force provides professional development around the Community Action and Problem-Solving Process for formal and informal educators who want to integrate civic and environmental action into their classroom. (Reprinted with permission from Earth Force)

CFW is implemented through in-school and out-of-school programming in an effort to connect the benefits of the competition to classroom curricula. Educators reinforce science concepts through water quality monitoring and data analysis. Math is supported through site analysis, like calculating the slope of the schoolyard or the area of a parking lot, and budget creation, which is a mandatory part of each proposal. Reading and writing are taught through proposal writing, which includes an overview of the project, background on the watershed, an explanation of the issue they are trying to solve, and a description of their solution.

“Much of the curriculum is going to be project-based learning, so Caring for Our Watersheds fits nicely into the classroom,” said Faiza Alam, a 7th grade science educator at Lanier Middle School. “I overlay the program with the 7th grade science curriculum, Understanding Our Environment.”

Sharing Environmental Success

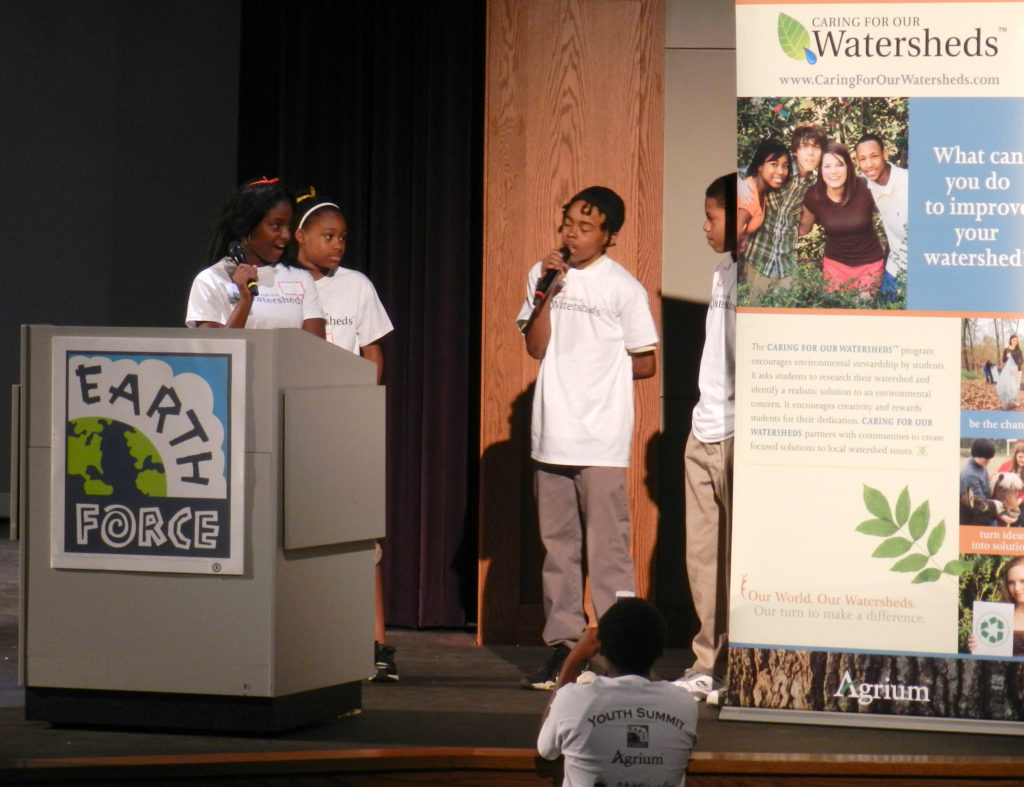

One of the most rewarding aspects of the competition is the presentation. After all of the students’ hard work, the presentations are an opportunity to reflect and celebrate their success. Each proposal is scored by a team of judges, and the top ten proposals are selected to present live to their peers, the community, and a panel of experts.

CFW in Virginia and Washington DC is unique, as it is the only competition that is combined with a larger environmental youth summit. Both events draw over 500 students and hundreds of additional community partners, and create an exciting and prestigious environment for the student presenters.

Not only do the CFW students present to much larger crowds compared to other programs across the globe, they also connect with other students from across the region who are doing environmental work at their school and in their communities. Over two-dozen partner organizations such as federal, state, and local agencies and NGOs run hands-on learning activities for the students and talk to them about career opportunities.

During the presentation, each group is given five minutes to deliver a clear and concise overview of their project to the appointed panel of judges. In the past, judges have included state representatives and employees from the Environmental Protection Agency, Office of the State Superintendent of Education, CH2M, Metropolitan Council of Governments, and the Virginia Cooperative Extension, among other organizations. The students are then ranked on their ability to articulate their issue, the feasibility of their solution, innovation, and their communications skills. Winners are selected by combining the written proposal score and the in-person presentation score. Each top ten group receives some level of prize money, ranging from $300 to $1,000.

Students from Jefferson Middle School in Washington DC present their CFW project.

Photo|Earth Force

Developing Environmental Problem-Solvers

A student from Lanier Middle School said, “It feels really good to be considered an environmental problem-solver because you are quite literally changing the world that we live in in a positive way. Caring for Our Watersheds has helped us with our communications and presenting skills, and has been a really good experience.”

CFW works to reinforce academic and civic skills, both of which are key to creating lifelong environmental problem-solvers:

- 91% demonstrate increases in 21st century skills such as problem-solving, civic action, and decision-making.

- 74% of students increase their ability to meet academic standards.

- 72% of educators notice an increase in their students’ interest in science.

- 56% of students show an increase in the ability to identify and use the skills needed to make a team work well together.

- 62% of students show an increase in the ability to “talk to people you don’t know about an issue you think is important.”

The program also has a considerable impact on conservation, as each group must be able to measure the environmental impact of their project. In the examples below, students have stopped 18,000 plastic bottles from entering landfills and potentially the Chesapeake Bay, are eliminating algal blooms in two local water bodies, and will filter 66 gallons of rainwater per storm before it enters Rock Creek and ultimately the Chesapeake Bay.

Caring for Our Watersheds in Action

Students throughout Northern Virginia and Metro-DC are doing big things to improve their environment. In 2015 alone, CFW reached over 500 students who took local environmental action.

Students at Lanier Middle School in Fairfax, Virginia are working to ban bottled water in their school. Last year, students proposed installing water bottle filling stations to reduce bottled water use, recognizing that water bottles often end up as plastic pollution, which eventually makes its way into the Chesapeake Bay.

After informing their community about the dangers of bottled water at the 2015 CFW competition, the students received over $9,000 to install six water bottle filling stations in the lower halls of their school. This year, they want to install two additional water bottle filling stations on the upper floor, impacting an additional 500 students.

Overall, data from the water bottle filling machines shows that roughly 18,000 bottles have been refilled in only half a school year. The students estimate that is the equivalent of 392 pounds of plastic saved from landfills. Through the 2016 CFW competition, they won an additional $800 to go toward two extra filling stations, which they believe can stop an additional 20,000 bottles from entering the bay. The fountains will be installed before the 2016-2017 school year begins.

“I joined this cause because I had noticed lots of my friends and family using bottled water. I had heard about the harmful effects of this, but not in depth until taking part in this project,” said Ryan Phillips, an 8th grade student at Lanier Middle School. “I think I have helped many students and teachers change their use of plastic, much like I have changed mine. I hope that by continuing this project I can affect the lives of many more students and teachers.”

In Reston, Virginia, students at Dogwood Elementary School are concerned about the rise of algal blooms in the Sugarland Run Headwaters watershed and want to lead the charge in cleaning up existing blooms and preventing future blooms from occurring.

The school’s eco-school club has monitored the growth of algal blooms in a local pond for about two years and believes the blooms may be having an adverse effect on the aquatic environment. They learned that one of the causes of algal blooms is when humans add nutrients to their lawns. When it rains, the water runoff moves these nutrients to lakes and ponds, causing algal blooms.

Dogwood students want to start doing routine water quality monitoring of two local water bodies, Stratton Woods Pond and Lake Audubon, with the aid of the Reston Association Watershed Management team and the Northern Virginia Soil and Water Conservation team. Their goal is to determine whether or not these are harmful algal blooms and to prevent them from growing in their local watershed. The students have already raised over $1,200 for this project. With the $900 prize from the 2016 CFW competition, they will be able to cover the costs for transportation and testing kits.

The members of the Student Sustainability Corps (SSC), an inclusive enrichment club at School Without Walls at Francis Stevens in Washington DC, are working to protect Rock Creek, which feeds into the Chesapeake Bay, from stormwater runoff. Their plan includes creating a rain garden and a retention wall to trap the urban runoff, which carries pollution from their field and the school parking lot into Rock Creek. They worked with experts from Casey Trees and students from Engineers Without Borders at George Washington University to learn how to create a retention wall and rain garden. When complete, the rain garden will filter roughly 66 gallons of rainfall per storm, preventing pollution from entering Rock Creek.

Developing Lifelong Environmental Citizens

Earth Force believes if young people are engaged as environmental problem-solvers today, they will become lifelong environmental citizens. Through CFW, students get the opportunity to create solutions to real-world issues that are affecting their community. They are invested in the process because the issue they select is something they care about. Creating a knowledgeable populace that has the skills and motivations to address pressing environmental issues is the key to combating the challenges our environment currently faces. And that starts with young people.

About the Author

Kristen Mueller leads national communications for Earth Force, creating engagement and excitement around the nonprofit’s mission and its partners’ hands-on, minds-on programming. Specializing in traditional media and social media relations, Kristen brings youth voice and leadership to the forefront of the environmental education field.