By. Katie Rogers, Strategic Energy Innovations

At a school where some students aren’t even guaranteed their next meal, one teacher is creating a sustainable future for students and the planet alike.

Kahri Boykin teaches Green Technology and Energy Conservation (GTEC) at Yosemite High School in Merced, 150 miles southeast of San Francisco. He faces obstacles above and beyond the multitude of challenges an average high school teacher faces. Ninety-eight percent of his students are “severely disadvantaged,” with circumstances that hinder their ability to learn at school. Some of Boykin’s students are homeless, live well below the poverty line, exhibit behavioral issues, or don’t have a way to get to and from school.

“These obstacles ripple throughout all of public education and it comes to a head in high school,” says Boykin. “How do you prepare [students] fast enough for no longer being supported by the public system? It’s a challenge. I think it’s a challenge that the green economy can help address.”

When students first arrive in Boykin’s class, they don’t know the green economy exists. In GTEC, students define sustainability, quantify lifestyle changes, gain technical expertise, and get real-world work experience. “I think it’s enlightening for students. I think it actually begins to plant seeds of hope that this new industry is something that was birthed and accelerated in their era, in their generation, and it’s something they can participate in,” Boykin says.

Although he teaches his students hard skills like solar installation and energy auditing, Boykin is more interested in teaching critical thinking and creative problem-solving for a rapidly changing innovation economy. “How do you give [students] experience in a technological industry sector where the profile of the job doesn’t really exist?” asks Boykin. “It’s just getting started, it’s just being developed, the technology is advancing so fast. The way you do that is you focus on the core concepts, and that’s energy, environment, and utilities. These are the core concepts we can really extract critical thinking out of and help them solve real-world problems.”

Boykin knows, from experience, that these core concepts aren’t absorbed well when taught from a book. The Journal of Learning Studies backs him up: research shows project-based learning results in increased content retention, better problem-solving skills, and improved attitudes toward learning.

For GTEC, Boykin relies on project-based curriculum that is aligned to Next Generation Science Standards and Common Core State Standards: “We focus on defining sustainability, defining green technology, renewable energy, energy auditing, lifestyle changes, policy, cost. We really dive into the curriculum. But it doesn’t end there, because if we structure the classroom just from a book perspective – just from an instructional perspective – it doesn’t quite sink in. The concepts get missed often. So, we follow them up will multiple project-based learning opportunities.” Boykin does an annual school energy audit and his students participate in the SEI energy competition, where schools throughout California compete to reduce their electric bill and carbon footprint.

The project-based learning doesn’t stop there. “We do everything from kayaking on our local lake reservoir, to invertebrae testing, to solar installs, to campus energy audits, to mentoring fourth-graders, and building solar cars,” Boykin shares. “I’m at a point where I’m doing a project-based learning opportunity every two weeks. And that’s my whole focus. That’s what stimulates innovation from my perspective. Projects, projects, projects. Projects is where the innovation comes from.”

Earlier this school year, Boykin’s students developed an interest in water consumption on campus. They surveyed their peers and found fellow students weren’t drinking water while at school. Boykin prompted them to begin the critical thinking process: Why aren’t students drinking water? Why is drinking water important? Is water consumption connected to learning? Students’ research revealed that proper hydration is, in fact, connected to cognitive functioning. This served as a foundation for administrative support when the class decided to raise money to replace all water fountains on campus with filtered and chilled bottle fillers and to purchase stainless steel water bottles for every student.

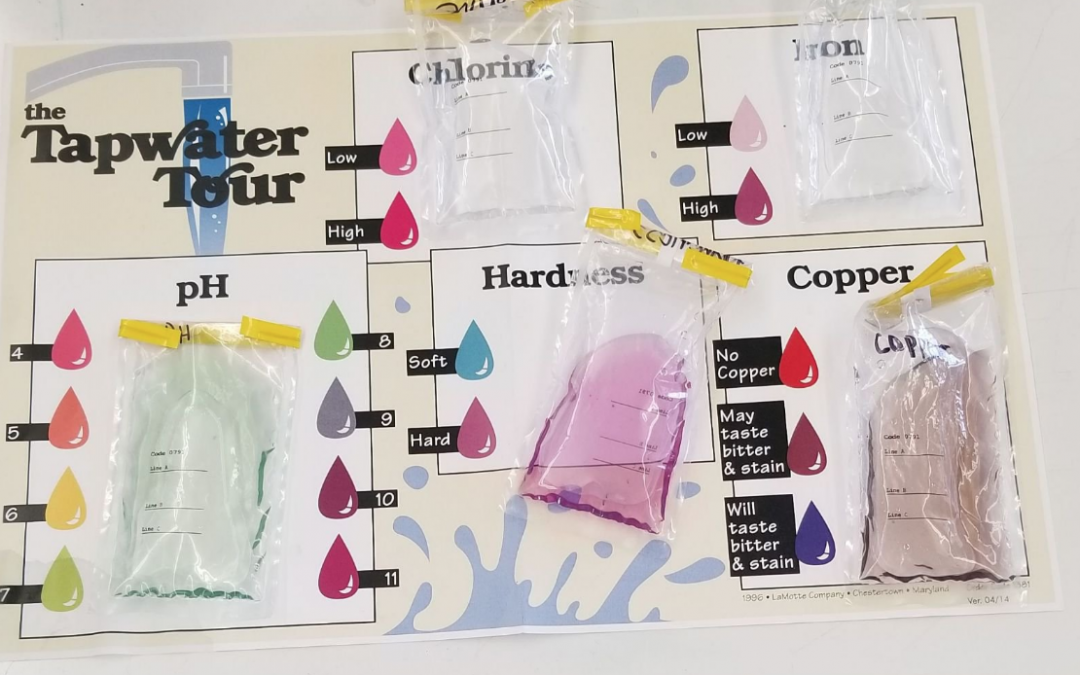

Boykin let the students lead with their newfound curiosity, and that campus water project spilled over into their surrounding environment. Students wanted to know where their water came from, so Boykin took them to Yosemite National Park. They collected samples and tested water from the Tuolumne and Merced Rivers, the major water sources for their community. What turned out to be a year-long Water Campaign was the result of students’ own creativity and critical thinking. Boykin marvels, “Once they understood that the water in their faucet came from this source, they started to get innovative: ‘Let’s go test it, let’s go see what’s affecting it, is it clean, is it drinkable, how is policy related, how is economics related, are there businesses involved?’”

GTEC students are already scheming about next year’s project. Their curiosity is currently piqued by their campus’ ground-mounted solar array. They have plans to design a tiny house-like structure with a hydroponic vertical garden inside, all powered by electricity from existing solar power. “This is all their innovation. It’s kind of crazy!” exclaims Boykin.

This is Boykin’s fifth year teaching, and he can now “totally understand why teachers need summers off.” His summer plans include taking a long nap, and attending a week-long Innovations in Green Technology teacher training.

Boykin and his GTEC students are @gtecdragons on Twitter.

Author Bio

Katie Rogers leads communications and marketing efforts for Strategic Energy Innovations (SEI), a nonprofit organization that builds leaders to drive climate solutions through environmental education and green workforce development. Katie supports SEI’s program teams that work on a variety of environmental education and sustainability capacity-building projects. Prior to joining SEI, she worked in marketing and advertising in California, New York City, and Seattle. Katie holds a Masters of the Environment degree in Sustainability Planning and Management from the University of Colorado, Boulder, and a Bachelor of Arts in Communications and Anthropology from the University of California, Santa Barbara.