By. Tashanda Giles-Jones, Environmental Charter Schools

Defining environmental literacy is crucial when you are cultivating a curriculum that fosters a sustainable school culture. According to California’s Blueprint for Environmental Literacy, “An environmentally literate person has the capacity to act individually and with others to support ecologically sound, economically prosperous, and equitable communities for present and future generations. Through lived experiences and education programs that include classroom based lessons, experiential education, and outdoor learning, students will become environmentally literate, developing the knowledge, skills, and understanding of environmental principles to analyze environmental issues and make informed decisions.” This is the definition of environmental literacy that we abide by at Environmental Charter Schools (ECS).

ECS is a network of three campuses: our high school (ECHS) located in Lawndale, California, Gardena Middle School located in Gardena, and Inglewood Middle School, located in Inglewood. Each school site was established to serve its immediate community. A primary focus of ECS is to provide students with real-world access to their communities and beyond, and to use these spaces to explore their history, be grounded in environmental principles and concepts, and think and act with scientific principles as guides. To use communities as living labs, we must arm our students with the knowledge they need to observe with focus, identify issues that matter to them, research those issues with skilled practices and procedures, and find solutions using innovative thinking.

At ECS, we challenge our students to act while providing them with a scope and sequence of learning experiences that are content specific, yet interdisciplinary in delivery. Through varied frameworks, perspectives, and civic action, we engage the entire school population in relevant, ecological, and solution-based practices. The framework from California’s Blueprint for Environmental Literacy outlines six specific practices that we adhere to: Equity of Access; Sustainability and Scalability of Systems; Collaborative Solutions; Commitment to Quality; Cultural Relevance and Competence; and Variety of Learning Experiences.

Building interdisciplinary understanding around environmental literacy among teachers is essential for changemaking curriculum. If the goal is to implement education in K-12 schools to achieve environmental literacy, then students must have quality access to environmental vocabulary, content, and experiences at each grade level. In addition, teachers must be comfortable integrating a significant level of environmental knowledge into their content specialty, whether they teach core or elective classes, and identifying topics that speak to each discipline. At our middle school campuses that would include Games and Movement, Art, College Readiness, ELA, History, Math, and Science. Grade and content level teams need to plan lessons together that share the same theme across all disciplines and create environmental storylines that promote student-centered civic action projects.

Yet, this kind of collaboration and curriculum design can be a challenge when core subject teachers haven’t been given appropriate training that would help them integrate environmental content into their lessons. When teachers don’t possess a comfortable understanding of environmental content, this can lead to disconnected learning for students (e.g., the absence of a deep connection to the content) and fewer opportunities for interdisciplinary collaboration between teachers. At ECS, we built in solutions to provide teachers access to environmental content knowledge that makes sense for their core subject area through targeted professional development. Together, we work on ways for students to access their core discipline learning through an environmental perspective. An example of such learning happens during our Interdisciplinary Benchmark Assessments (IBM), our version of a midterm or summative final.

Collaboration plays a big role in ECS’ success in providing environmental literacy for all our students, especially during IBMs. For example, one IBM had our students look at gentrification in Inglewood and the impact of building a renewable energy facility. They were challenged to look at the economic makeup of the residents, the income advantages and disadvantages of the city, development and its environmental impacts, and the cultural impact of gentrification. The eighth-grade team – consisting of two ELA/History teachers, one Math teacher, one Science teacher, and a variety of specialty teachers – spent months planning an integrated performance task and unit exam that included all four disciplines in addition to specialty classes. Each core class taught an aspect outlined in the learning targets while specialty classes focused on various outputs of knowledge.

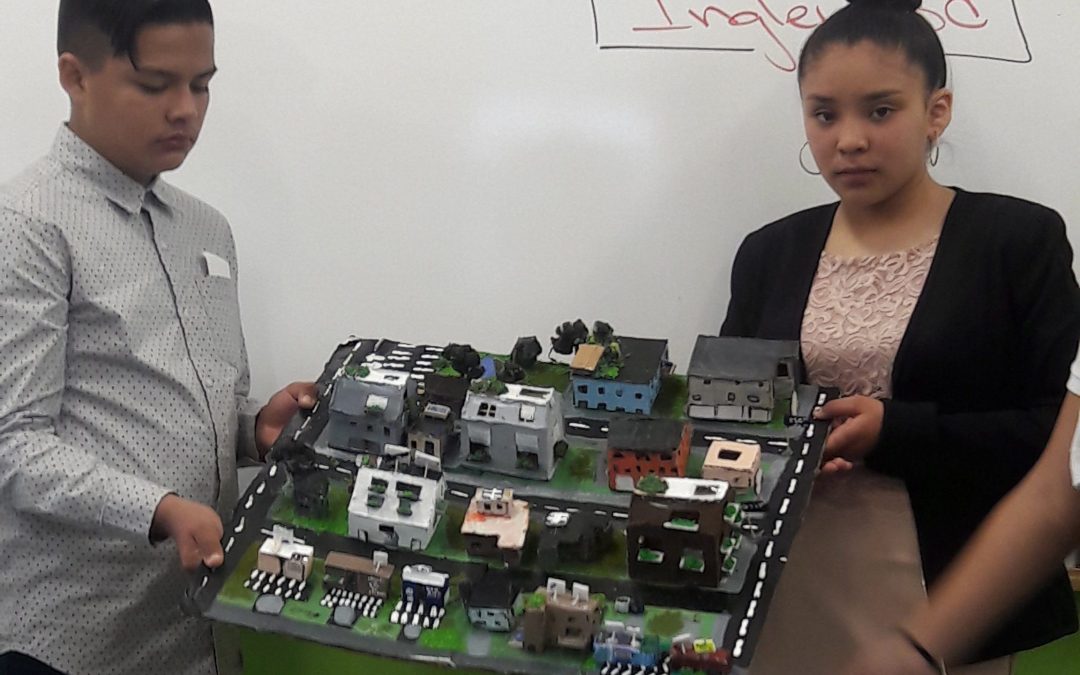

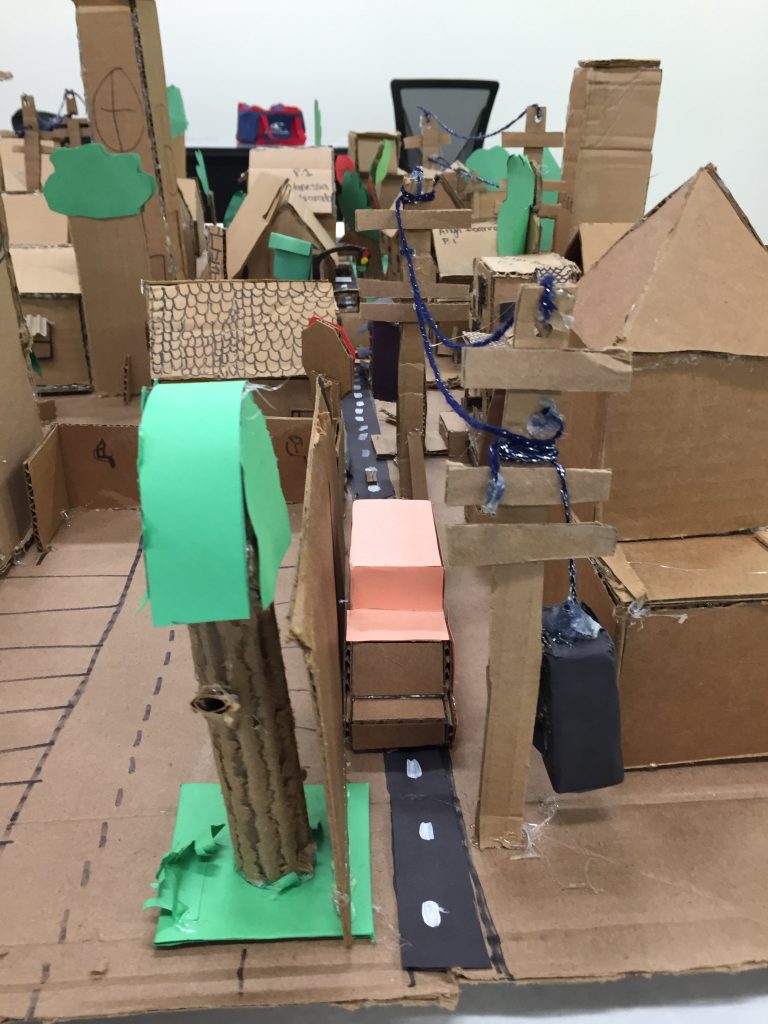

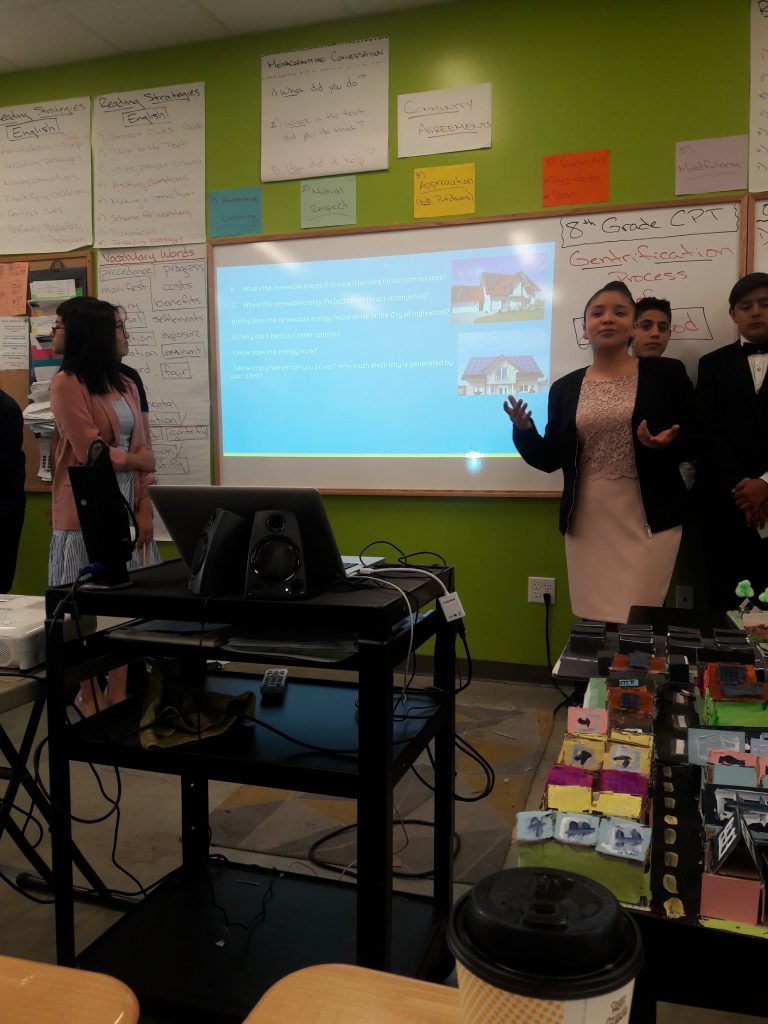

As teachers were planning out this IBM, they identified specific expectations for assessing learning and made sure to plan with an environmental literacy lens that followed the California Blueprint’s six principles. The classes were divided into teams who worked together to create a three dimensional blueprint of a new sustainable Inglewood community. In their communities, they had to provide all the essential elements required in a city, along with environmental aspects to make it sustainable. Additionally, the teams created brochures providing justification for gentrification and relocation, as well as presentations that explained the functions of their city. The teams then presented their proposals to a committee of decision-makers (school administrators, academic coaches, teachers, and staff).

Core subject areas were woven in throughout this project. Students used math to calculate the amount of land needed for new residential development and to determine what additional resources a growing population would need while trying to sustain the current population living in Inglewood. In ELA, students learned about effective communication and were challenged to come up with collaborative, sustainable solutions for urban development that were detailed in written proposals. In science, students identified the environmental impacts associated with gentrification and the local practices a community can adopt to develop with those impacts in mind. Students also looked at energy outputs and determined how many homes they would have to power with renewable energy, paying close attention to the quality of utilities they could offer their community.

History took students on a journey through civil and human rights that highlighted times where change was needed for the sake of all people and the commons. It is through the lens of cultural relevance and competency that students were challenged to sustain the existing population of residents while paying attention to their cultural needs, preserving their way of life, providing better access to healthier options, and decreasing the negative impact of environmental degradation as a result of development.

Equity of access played a role throughout this project as students had to identify the city’s most vulnerable populations, development happening due to gentrification, and the impact of renewable energy on residents. Students had to inform community residents about their plans for a new renewable energy facility and relocation. They had to convince residents of the benefits of gentrification and how the relocation would be handled fairly. This course of learning provided teachers the opportunity to utilize some equity strategies provided during implicit bias training, while including an environmental storyline that addressed renewable energy.

For the culminating project assessments, students had to create a 3D map of Inglewood and provide additional graphs and/or charts to help present their proposal. They developed a Google Slide presentation of their plans, blueprints, and processes, as well as a brochure for residents that detailed the problems they wanted to solve and why. The brochure also included their plan and a map for relocation, discussing what made their relocation plan fair and the benefits residents would receive during the relocation process.

Overall, the IBM planning process allowed for an integrated approach to teaching, while introducing a variety of perspectives from developers, residents, city officials, and environmental agencies. Through these perspectives, teachers were mindful of developing an environmental storyline that cultivated the environmental literacy that students required to determine the need for a new energy economy and understand system demands, limitations, and what’s required in urban development. It is this level of teaching that challenges our teachers to become knowledgeable in environmental content that is integrated into their core subject. Interdisciplinary planning and assessing boosted the teachers’ specific content strengths while providing them with the support needed to achieve performance expectations, such as constructing an argument supported by evidence for how increases in human population and per-capita consumption of natural resources impact Earth’s systems.

The more literate in the environment, both natural and man-made, students were, the more successful they were at achieving the IBM’s specific performance expectations. As we adapt and modify these projects each year and use student outcomes in our reflection process, we identify points of access where we can explicitly frame the work around environmental literacy better and cultivate a deeper understanding that will engage students beyond an IBM project.

Author Bio

Tashanda Giles-Jones is a Green Ambassadors teacher at Environmental Charter Middle School Inglewood located in Inglewood, California. Green Ambassadors is a specialty class where sixth- through eighth- grade students learn about environmental issues through innovative, place-based projects and action-focused learning. Tashanda develops lessons that teach the importance of, and the processes that lead to, environmental and human impact. With a student-centered and interdisciplinary approach, lessons are adapted to the student’s reality while providing engaging learning activities through garden-based education.