By. Abby Randall, EcoRise

To foster environmental literacy for every student, at every grade level, sustainability education cannot be limited to after school programs and summer camps. It must be deeply embedded into the school day, in every classroom, in every subject. Schools that are most successful at fostering environmental literacy leverage their school buildings and grounds as laboratories for applied, problem-based learning. This allows students to develop a deep understanding of sustainability concepts on a global level while applying these complex topics at a hyper-local scale.

In the spring of 2015, my sixth-grade students at Lamar Middle School in the Austin Independent School District (ISD) in Austin, Texas were engaged in a comprehensive air quality audit as part of a science unit on the atmosphere. Students explored the school campus in small teams, collecting data on indoor and outdoor air quality. They recorded the ingredients and chemical formulas of cleaning supplies, made notes about the presence of mold and mildew, interviewed the school nurse about rates of asthma and related student absences, and surveyed staff about odors and perceived air quality.

During their audit, one student group stumbled across the parent pick-up zone about 30 minutes before the end of the school day. They observed a long line of minivans, idling in the hot, humid weather characteristic of May in Central Texas. Armed with clipboards and curiosity, the students recorded the number of vehicles and the smell of the exhaust building up around the school’s front entrance. They quickly returned to the classroom to report their observations and hopped on a computer to research idling’s impact on air quality. Afterward, I helped my students calculate the carbon footprint of a range of idling vehicles and uncovered the relationship between exhaust, air quality, and respiratory illness. Convinced that idling was bad for their health and the environment, they begged me to take action.

“Ms. Randall, can you please tell the parents to stop idling?” I imagined a crowd of indignant parents complaining to my principal about the tree-hugging science teacher who asked them to turn off their engines while their small children melted in the back seat. I encouraged my students to come up with a different approach.

After doing some brainstorming, my students created signs with poster board and markers that read “No Idling in the Pick-Up Zone!” and were replete with images of sick children and wildlife. The posters seemed to have a small impact as a few sympathetic parents turned off their engines. And then a colossal Texas thunderstorm rolled through, soaking the posters until they were illegible. Not to be deterred, my students created flyers to educate parents about the effects of idling on human health and the climate, as well as the amount of gas and money being wasted. These innovative sixth-graders came up with a slogan – “Turn Your Engine Off So the Earth Doesn’t Cough” – and applied for – and received! – a micro-grant to purchase bumper stickers.

Armed with informational flyers and bumper stickers, my students visited the pickup zone, knocked on windows and educated – often pleading – with parents to turn off their engines. Within a week, there was not an idling vehicle in sight. My students calculated the impact of their project, estimating the tons of carbon saved through their no-idling campaign, as well as dollars saved. One parent called to tell me that her daughter was enforcing a strict no-idling policy for their family and even reached over to turn off the engine herself while stopped outside a convenience store in a grandparent’s car!

Empowered by their experience, these students went on to design an art installation of used plastic water bottles to educate the school community about the environmental destruction being caused by plastic waste. They erected a vertical garden in the cafeteria to grow greens for the school salad bar. They ran an outdoor learning competition to encourage teachers to take their students outside more often.

Now, as the Director of Programs for EcoRise – a social enterprise focused on igniting a new generation of green leaders – I oversee programs designed to foster environmental literacy and 21st century skills at 80 Austin ISD campuses and over 1,000 schools nationwide. Through standards-aligned curriculum, teacher professional development, and a Student Innovation Fund to make student green ideas a reality, EcoRise is creating an army of innovative youth with the knowledge and tools to tackle both local and global sustainability challenges.

EcoRise’s flagship K-12 curriculum is aptly named Sustainable Intelligence as it strives to build a foundation of environmental literacy and sustainability knowledge. Students are introduced to the concept of sustainability through a hands-on lesson that models the distribution and consumption of resources in a fishing simulation. Students quickly discover that if they take more fish than can be sustained through the replenishment rate, there aren’t enough fish left to feed any of the participants’ families. Subsequent lessons – there are over 160 lessons in English and Spanish – help students understand global issues, from climate change and the availability of potable water to the pros and cons of electric vehicles, and provide them with the skills they need to tackle the issues that have the greatest impact on their local community.

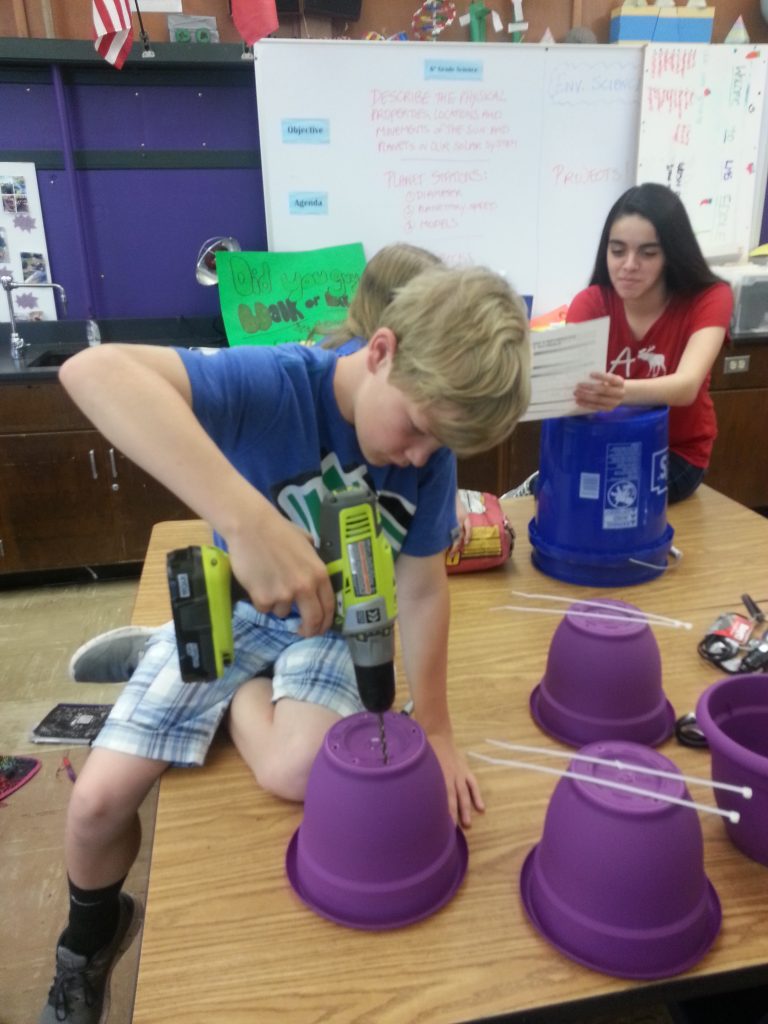

Through personal and school-based eco-audit activities, EcoRise students collect data related to one of seven themes – water, waste, energy, food, air quality, public transportation, and public spaces – and use it to identify a specific sustainability challenge at their school. Then, through EcoRise’s Design Studio curriculum, students harness the power of the engineering design process to work together to come up with specific, measurable solutions and submit grant applications to EcoRise to fund their solutions.

In addition to environmental literacy, the process develops students’ financial literacy as they create itemized budgets; scientific literacy through inquiry, data collection, and analysis; and myriad 21st century skills as they collaborate and leverage technology to collect, analyze, and communicate their data and ideas. These experiences also foster literacy in the traditional sense of the word, as students research, read articles, record observations, formulate conclusions, engage in persuasive writing and speech, and gain grant writing experience.

In 2019, environmental literacy is deeply embedded in classrooms throughout Austin ISD. At TA Brown Elementary School, students are preparing to move into a new, LEED© certified campus complete with a nature loop, water cisterns, nature play area, low-flow faucets, and dark-sky compliant lighting. EcoRise is working closely with TA Brown Principal Veronica Sharp and her staff, as well as Austin ISD’s Sustainability Manager Darien Clary and Outdoor Learning Specialist Anne Muller, to ensure that all staff and students have a deep understanding and appreciation of the different green features of their campus so that they can maximize their new building’s potential.

Through this form of place-based education, students not only develop a deep understanding of environmental concepts such a renewable energy, water quality and conservation, and greenhouse gas emissions, they also have the opportunity to apply this knowledge to increase the sustainability of their school building, their homes, and their community.

To prepare for their move, TA Brown students have been auditing their current learning spaces – their classrooms are housed in portables at a neighboring elementary school – to better understand how they are using public spaces and design solutions to increase green space and outdoor learning, regardless of location. Students had an opportunity to present their work to Austin Mayor Steven Adler at the Fifth Annual Student Innovation Showcase, hosted by EcoRise and the City of Austin Office of Sustainability. For each adult that stopped to chat with these creative young students, their knowledge of and passion for sustainable outdoor spaces was evident.

Three miles north at McBee Elementary School, teacher Alma Schell and her pre-K students read the book Up in the Garden and Down in the Dirt and then conducted a public space audit to find organisms – such as pollinators and decomposers – on their campus that are necessary for a thriving garden. Schell wrote in their grant application, “as we walked around the campus the students realized that the hunt was unsuccessful.” They applied for a grant to purchase supplies to create, tend, and observe a thriving, biodiverse school garden. “This project is important to the social-emotional, cognitive, and physical development of each of my students,” Schell explained. “The ability to have students access an outdoor learning environment that will help develop language, problem-solving skills, as well as social skills is necessary to create lifelong learners who feel connected to their campus and community.” While many preK-12 teachers share the misconception that sustainability is best taught in science class, Schell had no problem creating a cross-curricular unit to develop their language skills and environmental literacy.

For myself, Austin ISD teachers, and the EcoRise team, the question remains: how do we effectively measure environmental literacy? The Cambridge Dictionary defines literacy as “the ability to read and write; literacy is also a basic skill or knowledge of a subject.” If environmental literacy is defined as a basic skill or knowledge of environmental sustainability, then environmentally literate students – or those with a sustainable intelligence – are able to comprehend and communicate complex information about environmental challenges on a global scale and have the motivation and skills necessary to tackle these challenges at the local level.

Through end-of-year surveys, 91% of EcoRise teachers reported that EcoRise resources have had an impact on student environmental literacy and 82% of EcoRise teachers reported that their students adopted one or more sustainable behaviors such as composting, recycling, conserving water and energy, carpooling, eating healthier and more sustainable food, and/or using reusable water bottles and utensils. Forty-six percent of EcoRise students reported that they have started discussing how to protect their natural environment with friends and family and 78% of EcoRise students agreed that their actions and choices have a direct impact on the world around them.

One Austin ISD middle school student explained, “Eco-Audits really made me think about my energy and product usage and made me environmentally conscious,” while a classmate reported, “I appreciated learning about our school’s carbon footprint and being able to find out some easy ways to conserve energy and reduce carbon emissions. I like that we got to have a ‘real life experience’ that can actually help us make a difference in our community.”

To learn more about EcoRise and access free pre-K-12 sustainability and design lessons from five leading-edge curriculum suites, visit www.ecorise.org.

Author Bio

Abby Randall is Director of Programs for EcoRise, where she oversees implementation of leading-edge educational resources at over 1,000 schools across the United States, including sustainability and design curriculum, professional development, and a K-12 grant program that brings students’ green innovations to life. Abby has spent the last 13 years teaching, facilitating professional learning experiences, and designing curriculum for K-12 science courses and alternative education programs. She holds a B.A. in Anthropology from Trinity College and an M.S. in Agriculture, Food, and Environment from Tufts University Friedman School of Nutrition.