By. Carolyn Kolstad, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s Schoolyard Habitat Program Coordinator

A voice that pulls at your heartstrings can move you into action.

“When a child gets to eat a fresh tomato that they’ve grown, a kid who’s never had a tomato, and they bite into it, and they like it. It just makes your heart pound!” Holding her hands close to her chest, as if to contain her heart, a very emotional teacher, Becky Brunger of Environmental Charter School, describes what it is like to watch students learn and grow in their school garden.

As we celebrate “Greening Schoolyards Month” this May, it is important that we recognize the partnerships and the value they bring to students, schools, and communities. Whether you are planting native plants in a Schoolyard Habitat, reading Henry David Thoreau, or creating inspirational art from recycled materials, ALL experiences contribute to a student’s knowledge and eventual attitudes and actions. This compilation of experiences is how a synergy is formed and the child begins to grow. The collaborations bring action to the words “One Voice, One Movement,” a slogan that was created at the 2015 Green Schools National Conference.

Photo | Carolyn Kolstad

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s Schoolyard Habitat Program was founded in an effort to facilitate outdoor experiences for students. The building and nurturing of a green schoolyard, whether it is a forest, wetland, meadow, or garden, is an interdisciplinary learning opportunity for teachers and students alike. Outdoor habitats open a door of possibility for teachers looking to complement classroom lessons in not just math and science, but English, social studies, art, and music. Beyond the four walls of the classroom, these spaces afford students an opportunity to become stewards of the land by using hands-on learning to develop an appreciation for their environment and the role they play in keeping it healthy and sustainable.

This spring in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, I was able to see for myself how green schoolyards are having an impact on teaching and learning in our school’s classrooms. As an attendee of the 2016 Green Schools Conference and Expo, I participated in several sessions that illustrated the impact that ecological literacy and green schoolyards are having on our students, as well as the powerful role that partnerships can play in making green, healthy, and sustainable schools a reality.

Ecological Literacy at the Environmental Charter School at Frick Park

I kicked off the conference by attending one of the pre-conference workshops. The workshop I chose was “An Immersive Experience at the Environmental Charter School,” a field trip to Pittsburgh’s Environmental Charter School at Frick Park (ECS), a K-8 urban charter school that uses ecological literacy as a basis for curriculum and student development. Our group was met by a trio of school administrators who would be our tour guides for the remainder of the day. The core of this school is strong, built by individuals who harnessed their love of nature and education and connected them by creating ECS.

“The administration needs to be behind you. We feel really strongly about this and we have that here.”

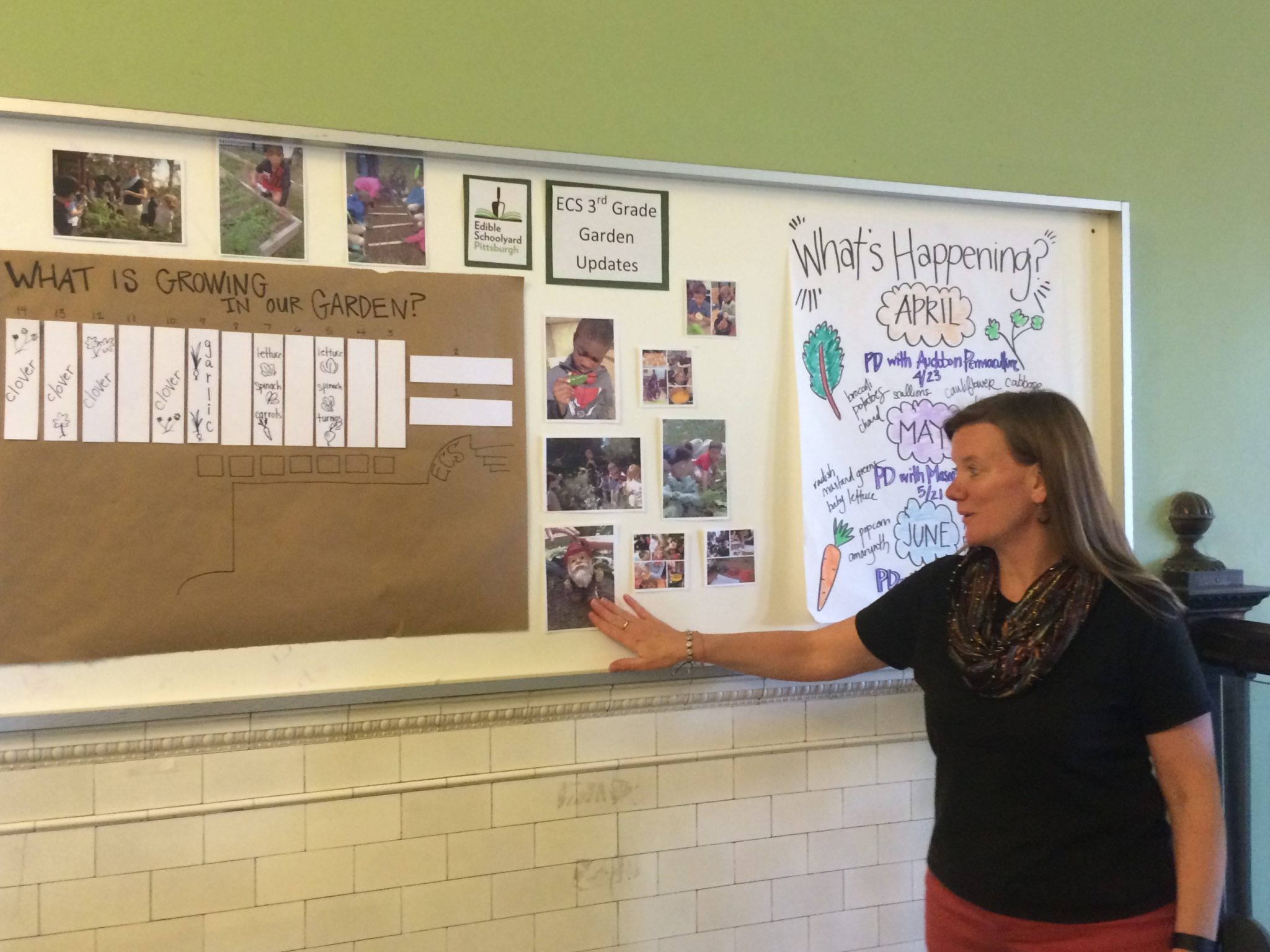

This sentiment could be felt throughout the day as we met with various students and teachers at ECS. We were able to witness the creative teaching and learning that was taking place in the Learning Lab, where students are taught different subjects together, seamlessly as one. Today, students were sharing their knowledge about rocks and minerals, which they captured eloquently with photographs and writing. We also met with the math, literacy, and social studies teaching group who had recently been to Berkeley, California to be trained at the “Edible Schoolyard.” On this day, their second and third grade students were learning to use knives, set a table, and celebrate African American culture by creating a soul-food inspired lunch. What I found especially inspiring about this part of the tour was how well connected the teachers were with the other “less education focused” benefits of being outside.

“Students need creative free play time outdoors, extra time to unwind, to be able to recharge their systems, to just be outside, to play with sticks.”

One of the best parts of this workshop was being able to engage in an outdoor activity with ECS students. Our group was split up and paired with 4th graders for a fossil tour through Frick Park. This was not just any tour. It was a tour that the students had created using Google Maps, uploading photos of fossils and writing the scientifically appropriate descriptions of them. Two students, Clemy (short for Clementine) and Abe, explained how the ocean was in that very spot more than 300 million years ago, and when we arrive at the ancient lakebed, now a stream, we will see for ourselves the fossils left behind. Notably, Clemy reminded us that “we need to respect the animals’ homes and be quiet, we are guests here.” We explored the ancient ocean fossils for nearly an hour as the students used toothbrushes to brush away debris so we could see them more clearly embedded in the rocks.

Communities as Outdoor Classrooms

“I see, I think, I wonder.” These words were written on a scratch pad of paper given out during the field trip, and compelled me to attend Friday’s session entitled “Outdoor Classroom: Connecting Learners and Community through Environmental Science and Service Learning” presented by Shakopee High School’s Science and Social Studies teachers William Koenig and Edward Loiselle. Mr. Koenig and Mr. Loiselle use a co-teaching model to engage their students in environmental science learning experiences. Following the steps of the scientific method, their students examine environmental and sustainability issues through project-based, service-learning activities. Both teachers guide their students throughout the year along their chosen project paths, serving as the conduit for student engagement within the larger community. At the end of the school year, Junior and Senior level students present their project results to a diverse audience including parents, teachers, students, and school board members.

“Let the students be leaders, let the students do the work. Sometimes they fail, but most of the time they blow us away! Giving students the responsibility to go out and experience real life situations can be scary, but most of the time it’s the most rewarding thing you can see them do. You see the students just grow right in front of you.”

Mr. Koenig’s and Mr. Loiselle’s passion for teaching, their willingness to take chances, and their faith in students has propelled their program from humble beginnings into a model community program. They demonstrated that by working together and making a concerted effort to involve the community, students are able to create more authentic, influential, and meaningful projects. Their presentation reminded me that outdoor classrooms do not have to be limited to the school grounds. Our communities can be classrooms too.

Partnerships Drive Success

The third presentation I attended was entitled “A Tale of Three States: Different Approaches to Successful Outcomes.” At the outset, the audience was asked to provide some examples of when the whole is greater than the sum of its parts. After a few silent moments the presenter provided some examples: “Peanut butter and jelly, Simon and Garfunkel” he mused. A quiet audience still. He went on to explain the ins and outs of the multi-state, multi-agency partnership his organization has been involved in to create healthy schools that foster learning and energy efficiency. He concluded that we must look to how others in our regions are succeeding and build from there. His beginning question about the whole being greater than the sum of its parts came together for me. When we work together, we accomplish more and what we accomplish is better and stronger.

So, how does this relate to green schoolyards? I have always said “you can’t be everything to everyone, but you can be great at what you’re good at.” The vision of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s Schoolyard Habitat program is that all of America’s children will have enjoyable and meaningful experiences in the out-of-doors, that they will understand the value of our fish and wildlife resources and their habitat, and will actively participate in habitat protection, conservation, and enhancement. This is our piece of educating the whole child. We teach the voice of stewardship. However, we cannot do our work alone. Organizations like the Green Schools National Network help connect us to educators, schools, districts, and other outdoor classroom/green schoolyard champions who can benefit from our program, and who have stories and best practices to share and learn from. When our voices join together to become a network of thought leaders, we are providing an example to our students that demonstrates the potential of true, meaningful collaboration. Together, we are empowering students to discover what is important to them and to use their voices to lead the next generation on the journey of “One Voice, One Movement” to transform schools for a sustainable future.

About Carolyn Kolstad

Carolyn Kolstad is the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s Schoolyard Habitat Program Coordinator. The program aims to provide opportunities for children to experience and learn about natural resources, and to enhance teachers’ environmental teaching methods through training and the planning and implementation of Schoolyard Habitat and Outdoor Classroom projects. In 2011, Carolyn co-authored the publication “Schoolyard Habitat Project Guide: A planning guide for creating schoolyard habitat and outdoor classroom projects.” She is on the advisory board for the Green Schools National Network.