By Anne Vilen, EL Education

Educators and policymakers alike acknowledge that sustainability education is good for the planet, but there is less consensus on how developing informed environmental advocates impacts achievement. EL Education schools—a network of 150 schools across the country, many of them serving urban and or low-income families—are answering that question with enviable academic results and equally stellar stewardship. EL Education’s portfolio includes three national Green Ribbon award winners, and many more schools that ensure kids develop both the aptitude and attitude to address the sticky problems of our global future. Leaders at EL Education schools share three common practices that get kids on the green way to getting smart.

Teach the Science (and history, and math, and language arts) of Sustainability

EL Education schools base their instruction on rigorous state and national standards in all subject areas, and research shows that students in these schools outpace their non-EL Education peers in math and reading (see demographic and achievement results from EL Education schools on their website eleducation.org). Behind these results is a unique approach that integrates multiple subjects into learning expeditions that investigate global environmental issues through the lens of local case studies. At Evergreen Community Charter School, a Green Ribbon school in Asheville, North Carolina, for example, fifth grade students learn about agricultural practices in history by interviewing local farmers and farm workers. Then they write letters, filled with evidence from their learning, to federal and state officials lobbying for changes in laws that impact migrant farm workers’ working conditions, how food is labeled, or how local food competes in the economy. You can learn more about how environmental education is woven through learning expeditions and school culture from their environmental stewardship blog.

Although learning expeditions always combine hands-on fieldwork and partnerships with local experts, they are first and foremost rigorous school experiences that develop students’ critical thinking capacities. In the video below, eighth graders at King Middle School in Portland, ME are reading a professional scientific article in preparation for investigating the viability of alternative energies in Maine’s energy economy. The science teacher, Peter Hill, spends several lessons teaching students to analyze this complex text and mine it for information. He notes, “I was talking to a scientist once and he said, my job is 10% experimenting, 40% writing, and 50% reading.”

Reading and Thinking Like Scientists—Day 1: Strategies for Making Meaning from Complex Scientific Text from EL Education on Vimeo.

Video | David Grant

To further connect the dots between academic standards and time studying sustainability both in and outside of the classroom, some EL Education green schools have aligned their science and social studies curricula with standards from the North American Association of Environmental Education (NAAEE) or the Education for Sustainability Standards and Performance Indicators. Such standards focus on academic skills like conducting research, data analysis, and evidence-based thinking alongside ecological citizenship and a sense of place. “Making environmental education standards-based is an organic process with lots of entry points. When we create a learning expedition, we ask what’s happening locally, regionally, nationally, internationally. Then we identify a science or social studies theme that illuminates the state standards and the NAAEE standards. All those parts are connected to make it come to life for kids,” says Susan Mertz, executive director of Evergreen Community Charter School. Notably, Evergreen boasts one of the highest science proficiency rates in the state.

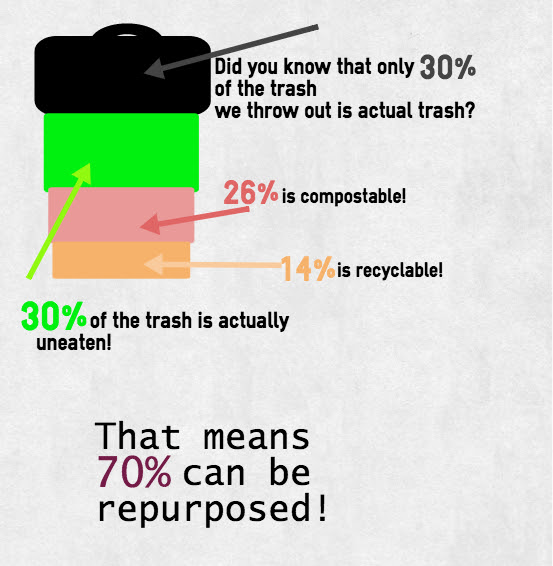

At Capital City Public Charter School, a Green Ribbon school in the heart of Washington DC, fifth graders stretch their literacy muscles by reading and writing about the impact of pollution in the Chesapeake Bay. They analyze water samples and learn from experts how to grow native plants in the classroom that they will later transplant into the Anacostia River. Based on their new understanding of the impact of pollution, students last year decided to teach others how to protect the watershed and Bay. For three days, students rummaged through trash in the cafeteria and separated the trash among recyclables, unused food, compostables, and waste. The students found that only thirty percent of the trash was actual waste, but much more was making its way into the bins, and eventually into the Bay.

Assign Authentic and Meaningful Work

Once students have a deep understanding of an environmental issue, they create the same kinds of products that professional scientists and historians create—ones that inform decision-makers or advocate for sustainability. The fifth graders who sorted trash at Capital City came to understand the difference people make—positive or negative—in the sustainability equation. So they worked to change their peers’ behavior by creating infographics for the cafeteria, like this one below.

Often students use the data they have collected and analyzed to make recommendations or build an argument that will be judged by stakeholders in the real world. At Casco Bay High School in Maine, students studied the chemistry of air and connected it to policy. They saw how even relatively small changes in the amounts of certain gases can impact their world in dramatic ways. Then in English class, guided by teacher Susan McCray, they learned to read policy documents and conduct research. They put the pieces together in a “white paper” on an environmental policy related to all of their learning. In a gathering not unlike a doctoral thesis defense, students presented their proposals before a panel of experts including environmentalists, legislators, lawyers, and government agency representatives. Students had to present the science and defend their proposals.

Often students use the data they have collected and analyzed to make recommendations or build an argument that will be judged by stakeholders in the real world. At Casco Bay High School in Maine, students studied the chemistry of air and connected it to policy. They saw how even relatively small changes in the amounts of certain gases can impact their world in dramatic ways. Then in English class, guided by teacher Susan McCray, they learned to read policy documents and conduct research. They put the pieces together in a “white paper” on an environmental policy related to all of their learning. In a gathering not unlike a doctoral thesis defense, students presented their proposals before a panel of experts including environmentalists, legislators, lawyers, and government agency representatives. Students had to present the science and defend their proposals.

The experts asked probing questions about how environmental factors interact, the accuracy of their research, and the details of their argument that made students defend their thinking with evidence. Many students stepped up the rigor of their thinking when a real audience challenged them with questions. Afterward, experts invited students to apply for internships, partner with them on doing further research, or to present to their own stakeholders. “They are always so moved by seeing young people who are this committed and knowledgeable. They always say our future is in better hands because these students will be lifelong active citizens,” said McCray.

Presenting their own work to an authentic audience both motivates and educates students. Many other examples of student work demonstrating deep understanding of and service in environmental issues can be found at Models of Excellence: The Center for High Quality Student Work, a collection of student project work curated by EL Education and the Harvard Graduate School for Education.

Photo|Evergreen Community Charter School

Foster Citizenship, Service, and Leadership

EL Education has its roots in Outward Bound and retains the value proposition of the outdoor education organization’s Design Principles, including

- Service and Compassion

- The Natural World

- Responsibility for Learning

In green schools, students embody these design principles through sophisticated ongoing service learning initiatives that go well beyond the occasional fundraiser or litter pick up. Students at the Metropolitan Expeditionary Learning School in New York City funded and built a community garden near their urban school. Now they are harvesting food to support their own their own learning and providing a space for their inner city neighbors to see how food is grown. The project was made possible with a variety of community partnerships, including one with the Queens Trust for Public Land, which is now working with the school on a multi-year project to design and build a greenway on an old railway bed that will serve the school and its neighbors.

Service learning projects like this require students to apply their academic skills and knowledge, but also build the habits of character that research has shown often make a bigger difference in students’ lifelong success (see, e.g., Paul Tough, Helping Children Succeed: What Works and Why, Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2016). “We learned how to come together as a community to help each other and accomplish a task, and also how to transform something useless into something better,” said a 6th grader who spearheaded the garden project. Collaboration, perseverance, vision, and problem-solving are exactly the qualities students will need to tackle the environmental problems of the future.

EL Education’s framework for achievement includes not only the mastery of knowledge and skills, but high quality work, and character creates a solid foundation for good education and for green education. Students learn the science of sustainability. They learn how to communicate their understanding through compelling images, words, and presentations. And they learn to lead transformational initiatives that improve the communities around them. At several schools–Capital City Public Charter, the Greene School, in West Greenwich, Rhode Island, and in the coming year Genesee Community Charter School in Rochester New York–students themselves have spearheaded efforts to document their schools’ green practices, and write the application for a prestigious Green Ribbon.

But going green is not just about winning awards. It invites students of all ages to appreciate the natural world and inspires them to take meaningful action as citizens and leaders. It also empowers them with the knowledge and skills they will need to be the superheroes of Earth’s future. Capital City Director of Instruction Jake Fishbein sums it up this way, “Environmental education is really about our survival as a species. When we know scientifically that we live in an ecosystem and our behaviors change or sustain that system, then the part in the EL Education mission that says kids ‘contribute to building a better world’ is not just a nicety. It’s a critical component of being an educated person on a suffering planet.”

About the Author

Anne Vilen is a writer and school coach for EL Education. She is the author of Transformational Literacy: Making the Common Core Shift with Work that Matters (2014) and Learning that Lasts: Challenging, Engaging, and Empowering Students with Deeper Instruction (2016). Previously, she taught language arts in middle and high school and served as Director of Program and Professional Development at Evergreen Community Charter School, a high performing school in Asheville, North Carolina and a member of the Green Schools National Network.