By. Anne Vilen, EL Education

In Braiding Sweetgrass, plant ecologist Robin Wall Kimmerer asks this profound question: “Isn’t this the purpose of education, to learn the nature of your own gifts and how to use them for good in the world” (Kimmerer, 2013, p. 239)? For teachers, Kimmerer’s question is a provocation to help students discover and use their gifts in the name of environmental and social justice. Across the EL Education network of schools, many teachers integrate science and social studies content with the arts not just to make the world more beautiful, but also to explore issues of equity and fairness. The stories of students painting, sculpting, writing, singing, and performing to protect the planet and its people are inspiring. What’s more, any teacher in any school setting, can do these four things to engage students in artistic acts of consequential service.

Teach the Content Behind Local Issues

Every community has issues—environmental, social, economic, or historical problems that impact its citizens and call for innovative solutions. Almost always these complex questions can be better understood through multiple disciplinary lenses: social studies, science, literature, and art. Teaching the scientific principles or social and historical dynamics of a problem like “How can we produce enough energy to power our economy without damaging our environment?” can lead to a multi-layered, rich understanding that fosters meaningful art.

History teacher Alex Wilson at Four Rivers Public Charter School in Greenfield, Massachusetts saw the energy problem as an opportunity for students to get smart and do good. “If you solve the energy problem,” he says, “all of a sudden [other] problems on that list have a pathway toward a reasonable solution, so teaching about the energy issue is really important.” In pursuit of understanding the energy problem more deeply, seniors at Four Rivers mapped the connections between economic, political, social, and scientific perspectives on energy and turned that map into a film documentary on the future of energy. Learning the skills to plan, write, shoot, and edit a film presented an artistic and intellectual challenge, but the payoff for students was a new sense of purpose and power. They screened their film in a local theater for a community audience and since have been invited to show the film in bigger venues. “It’s a great feeling,” said one student, “to think that what we’ve done has the power to change people’s minds and the way they think about this issue.”

Involve Experts and Use Professional Models to Teach Artistic Skills and Standards

Combining science, social studies, and art works best when teachers also collaborate to combine their gifts in support of students’ efforts. Four Rivers teachers partnered with experts in engineering, regional planning, and filmmaking to teach, mentor, and critique their students’ work. Such collaboration requires a great deal of logistical planning and strategic communication to keep the academic and artistic work on track, but the final result is worth it. Professional artists bring expertise that content-area teachers may not have, and can convey the standards of artistic excellence that transform “making art” from personal to professional.

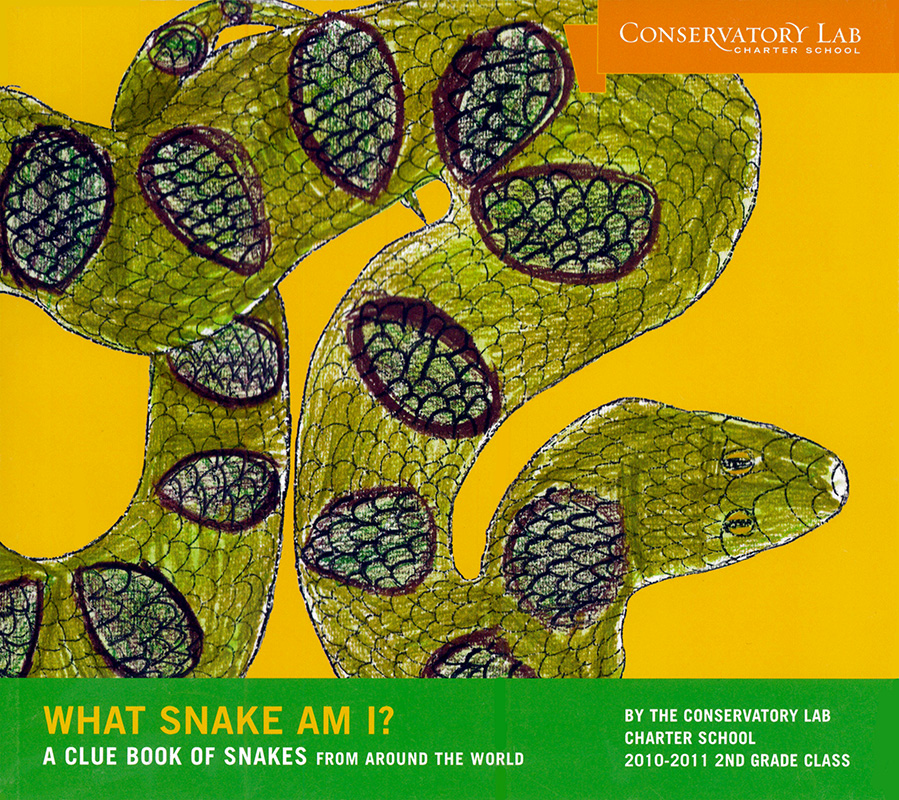

Be sure to plan for and preserve enough time for students to create and revise their work multiple times. Doing work that is accurate, detailed, and beautiful in conception and form takes time. Teach lessons in which teachers and students together critique professional and student-created models of high-quality work like those found on Models of Excellence, and give students kind, specific, and helpful feedback along the way that will help them do their best work.[1] You can see many of these teaching moves in this video, which features second-graders at the Conservatory Lab School in Boston, Massachusetts who created a music video and an illustrated e-book to teach viewers about snakes.

Watch the whole video series about this project to see how master teacher Jenna Gampel structures lessons to build students’ literacy skills and science knowledge while producing art with purpose and power.

Build a Bridge from Me and We

In schools, art is often seen as a means of self-expression. Students create art that reflects who they are, what they believe, and what they find beautiful. But art can also be an avenue to discovering and connecting with others—both the natural world and human “others” across town or across the world. Using art to understand others’ experience and perspective flexes students’ empathy muscles.

Genesee Community Charter School, housed in the Rochester Museum and Science Center in Rochester, New York, has a long history of using the arts to illuminate and address community concerns. Last year, curious about what some have called an “urban renaissance” in their city, Genesee sixth-graders asked the question, Whose Renaissance is it? To find out, they explored four different neighborhoods, looking for bridges and barriers to equity across the neighborhoods of Rochester. Investigating why some people in their community are poor and other are prosperous led them to ask: What is my responsibility as a citizen to stand up and challenge unfairness?

Students quickly pointed out that public art is one “bridge” that everyone in their city can appreciate. Teachers Alex Stubbe and Chris Dolgos then enlisted mural artist Shawn Dunwoody to work with students on their own public art project. Students painted murals honoring important African American figures and events in Rochester at four sites throughout the city. The mural project cultivated new friendships between city residents, and it also changed students. “The most important connections we made were with the people who live around the murals, because we needed to build bonds and listen to them to do what’s best for the community,” said one student. “I realized that the people I just met were not that different from me, I just have more privileges and opportunities,” said another.

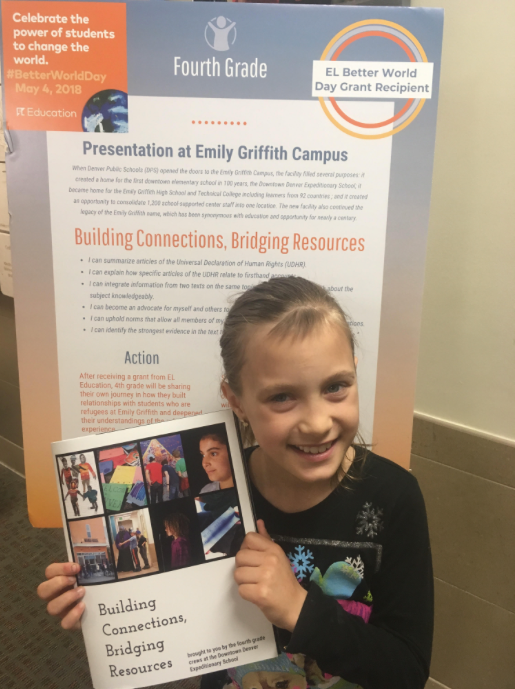

Fourth-grade students at the Downtown Denver Expeditionary Learning School similarly crossed the bridge from me to we by spending time with and interviewing refugees in their community. They turned the interviews into an illustrated book called Building Connections, Bridging Resources about how to be an advocate for refugees. The artwork for the book mirrors the paper-collage style of artist and social activist Romare Beardan. Students hosted a celebration to launch their book at a local refugee resource center, where they also volunteered and raised funds to support the refugees who had so generously shared their stories.

Make the World a Better Place

When students create art in the name of environmental and social justice for all, it has a lasting impact. Having an authentic audience with whom to share their art motivates students to change hearts and minds. In the process, students themselves become stewards of the planet and more engaged citizens. Each spring thousands of students in EL Education schools use art and action to celebrate Better World Day—a nationwide extravaganza of community service, learning, and student activism. While the showcase for these projects streams on Facebook Live and shows up in live tweets across the country on only one day each year, the learning and hard work of creating art for advocacy begins much earlier and makes a difference well into the future. This year Better World Day takes place on May 3; It will feature student-written books, student-created museum exhibits, and student performance art. You can see it in action here or follow the hashtag #BetterWorldDay across social media. Projects like these are meaningful and memorable to students. They matter most because they remind us all that thriving in a sustainable world is reciprocal and mutual. The trees, the soil, the water, and the diversity of our communities sustain humanity. And it’s our responsibility and our privilege—as teachers, students, and artists—to honor them and give back. As a powerful tool for advocacy, art is a gift that keeps on giving.

References

Kimmerer, R. (2013). Braiding Sweetgrass. Minneapolis, MN: Milkweed Editions.

Author Bio

Anne Vilen is Senior Writer for EL Education and co-author (with Ron Berger and Libby Woodfin) of Learning that Lasts: Challenging, Engaging, and Empowering Students with Deeper Instruction (Jossey-Bass, 2016). Previously, she served as Director of Program and Professional Development at Evergreen Community Charter School, a member of Green Schools National Network and an EL Education mentor school. Follow her on Twitter @ELEd_AnneVilen.

[1] My book, coauthored with Ron Berger and Libby Woodfin, Learning That Lasts: Challenging, Engaging, and Empowering Students with Deeper Instruction, provides tools, resources, and examples for teaching in and through the arts (pp. 226-274).