By. Jennifer Gaddis and Melissa Terry

John Dewey, the famed Progressive Era educator, was convinced that food held the potential to teach children about more than just nutrition. He saw school gardens as a pedagogically powerful platform for connecting children to nature and fostering a spirit of inquiry that cut across academic subjects. Likewise, home economist Emma Smedley, one of Dewey’s contemporaries, saw cafeterias as learning spaces with ties to art, health, domestic science, and vocational education. She oversaw Philadelphia’s school lunch program and believed it should be treated as “one of the arteries through which the active blood of co-operation runs,” not as “a mere appendage of the educational system” (Smedley, c.1930, pp. 191-192).

However, the idea that school lunch programs could be part of a comprehensive food- and garden-based curriculum, while popular in the early 1900s, enjoyed little traction during the first fifty years of the National School Lunch Program (NSLP), which was created in 1946. Fortunately, this has begun to change as the local food movement has gained momentum and concerns about high child obesity rates and young people’s lack of food literacy have attracted increased public attention. There are many ways to actively involve young people and the cafeteria workers who feed them in the process of improving their school food environments (and food systems more broadly).

In this article, we present two examples of participatory research done in collaboration with K-12 students and cafeteria workers to illustrate possible avenues of civic engagement within school food programs. What both examples—student-led food waste audits and worker-led campaigns for school food reform—share is the notion that students and workers can and should be treated as partners who are fully capable of collecting data, analyzing findings, and forming recommendations related to the environmental, economic, and educational aspects of NSLP and other federal child nutrition programs.

Cafeterias as Classrooms: Student-Led Food Waste Audits

Over the past two decades, the Edible Schoolyard, a nonprofit founded by Alice Waters, has helped to popularize the idea that cafeterias are classrooms. National nonprofits like FoodCorps, Slow Food USA, and the National Farm to School Network have further grown the movement for food- and farm-based experiential education. One of this article’s coauthors, Melissa Terry, a food policy researcher at the University of Arkansas, is among the many advocates within this movement who believe that identifying the educational aspects of school cafeterias can help reframe how we understand the potential for these spaces to function as important learning environments for our children. In collaboration with the World Wildlife Fund, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), and U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), she coordinates a national study of student plate waste. Unlike the vast majority of such studies—in which outside researchers visit a cafeteria to photograph and weigh meal components before and after the lunch period—Terry’s project engages K-12 students as researchers.

Through student-led food waste audits, young people gain hands-on experience measuring and analyzing what their peers are taking, eating, and throwing away. At the same time, they have the opportunity to acquire a deeper understanding of how the environmental, social, and economic context of NSLP shapes food waste and vice versa. More specifically, students learn to:

- Calculate food waste weights for meal components and graphically represent data.

- Understand and identify how individual choices impact our environment.

- Analyze the environmental impacts of food waste (e.g., 20% of all methane emissions are created by landfilled food waste).

- Estimate water and greenhouse gas resources embedded in wasted food.

- Contextualize the food waste in their cafeterias relative to the problem of food waste in the U.S., where 30 – 40% of the total food supply is wasted (63 million tons per year) and one in eight Americans live in a food insecure household.

- Design and implement innovative strategies to reduce the volume of food waste in their schools.

These learning activities provide educators with ample opportunities to begin treating school food as an integral part of the educational system through project-based learning, community engagement, and STEM cross-curricular connections. Moreover, these activities foster the development of 21st century skills (collaboration, creativity, critical thinking, and problem-solving) and environmental literacy. The eight states, nine cities, and 46 schools that have used this methodology in the World Wildlife Fund study —and others that subsequently use the toolkit that Terry’s team developed—are contributing to meeting the first-ever multi-agency (EPA, USDA, and Food and Drug Administration) national goal to reduce food waste.

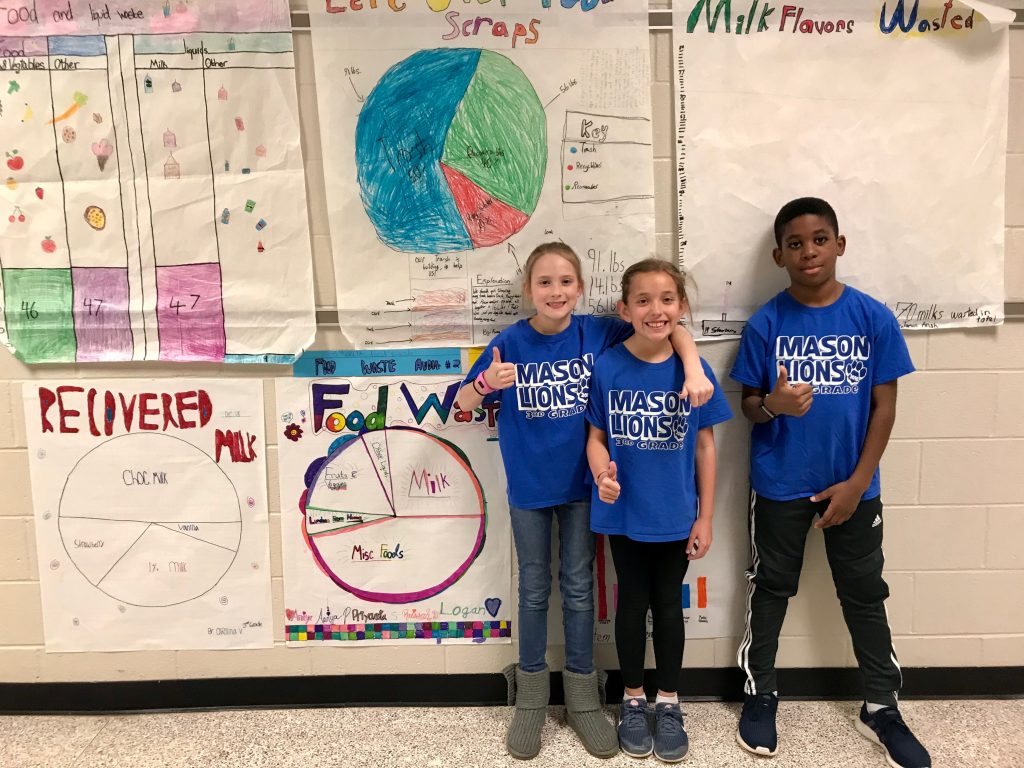

Gwinnett County Public School District Food Waste Audit

In the Gwinnett County Public School District (GCPS), located in the Atlanta metro area, the topic of engaging students in measuring cafeteria food waste aligned with curriculum objectives at many grade levels and across all subject areas. During the 2018 – 2019 school year, the district’s lead sustainability coordinator, Brenda McDaniels, worked with student-led Youth Advisory Councils to research, design, and implement food waste audit procedures. In the process, students learned about formal research methods, created data-based poster sessions, and presented their findings to a public audience that included the directors of their school nutrition program and members of the board of education.

The GCPS Nutrition Program’s leadership supported the students’ research findings and modified several key policies regarding packaging and waste. In addition, the district is starting to explore creative ways to increase student consumption of healthy food and is considering the reinstatement of reusable trays, utensils, and cups. “This kind of student-centered engagement provides a powerful opportunity for students of all ages to learn about and leverage their experiences in school cafeterias in a proactive manner that cultivates an ethic of civic leadership,” McDaniels told Terry.

While not all school districts have a dedicated sustainability coordinator, districts that would like to include this kind of position may find it helpful to use a performance-based contract model. For instance, by participating in the World Wildlife Fund student-led food waste audit, the Phoenix (Arizona) School District discovered that, with a few simple adjustments, they could reduce their solid waste hauling contract from a five-day-a-week service agreement to a two-day (Tuesdays and Thursdays) service agreement, which saved the district approximately $100,000. These kinds of savings can justify and fund additional staff positions that support scaling student-led cafeteria research into schools across an entire district.

Cafeteria Workers Organizing for “Real Food, Real Jobs”

While it’s important for students to learn these lessons, cafeterias can and should be spaces of civic engagement for all members of the school community. This includes the nation’s 420,000 school kitchen and cafeteria workers, who are not always treated as full and respected members of the school community. K-12 cafeteria workers provide for students’ physical and emotional needs, maintain the physical spaces where students eat, and engage in “community mothering” (i.e., weaving and reweaving the social fabric by fostering relationships and social connections) (Glenn, 2010, p. 5). As such, they are a vital part of the nation’s care infrastructure.

In her new book The Labor of Lunch: Why We Need Real Food and Real Jobs in American Public Schools, article coauthor Jennifer Gaddis, a professor of Civil Society and Community Studies at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, argues that initiatives to reform school lunch and treat cafeterias as classrooms will be limited in impact if frontline cafeteria workers are treated as a cost to minimize and aren’t adequately compensated or respected (Gaddis, 2019; Jacobs and Graham-Squire, 2010). Much of their work falls under the umbrella of “care,” which scholars Berenice Fisher and Joan Tronto define as a “species activity that includes everything we do to maintain, continue, and repair our world so that we may live in it as well as possible” (Fischer and Tronto, 1990, p. 40).

As she traveled the country from 2011 – 2016, visiting school districts at the leading edge of the real food movement, Gaddis met K-12 school staff in rural, suburban, small town, and urban school districts who taught her what’s possible when they become active participants in building and strengthening their communities. Some of the most striking examples were of labor activism—a form of civic engagement that is gaining steam with the #RedforEd movement and a new wave of teacher strikes that Los Angeles educators have dubbed a “fight for the soul of public education.”

Notably, however, the union density of school cafeteria workers is lower than K-12 teachers. While most unionized school cafeteria workers are part of public sector locals (often belonging to the American Federation of State, County, and Municipal Employees), they have less visibility in the national spotlight and their labor struggles are different because of their status as hourly workers. Moreover, the School Nutrition Association, the primary national professional organization that represents K-12 cafeteria workers, is a nonprofit association and not a labor union like the National Education Association or the American Federation of Teachers.

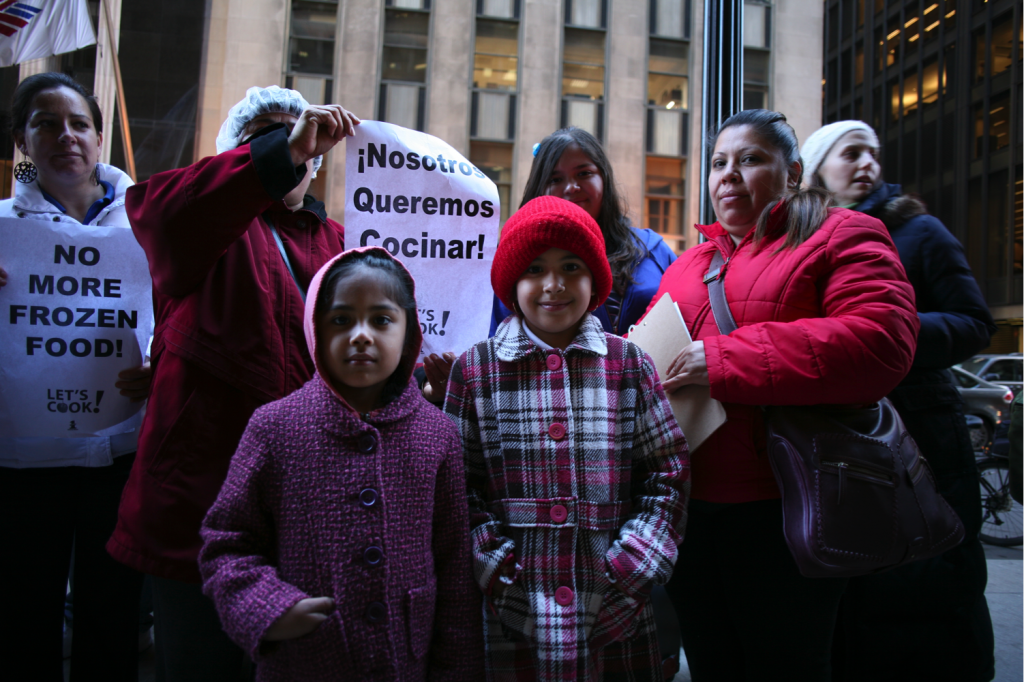

Despite their comparative lack of negotiating power, cafeteria workers belonging to Unite Here, the largest union representing foodservice workers in North America, have fought for the needs of their students and communities through Real Food, Real Jobs campaigns in Chicago Public Schools and New Haven Public Schools. In New Haven, an urban district where 62% of students qualify for free or reduced-price meals, this was just the latest in a series of forward-thinking campaigns.

As detailed in the introduction to The Labor of Lunch, in 2004, members of New Haven’s Local 217 organized to push the city to end its contract with Aramark, a multi-national foodservice management company that they believed had lowered both the quality of the food and jobs in their cafeterias. They gave public testimony at school board meetings, talked to friends and neighbors, and staged delegations of workers carrying signs and loudspeakers. The result—finally kicking out Aramark in 2008—was a victory for workers, who wanted, and won, a greater role in determining lunch policies and priorities. It was also a victory for the public, especially the tens of thousands of children who participate in the city’s breakfast and lunch programs, and the local farmers who stood to gain from a new focus on farm-to-school sourcing.

But the fight wasn’t over. New Haven’s two hundred cafeteria workers had suffered tremendous economic hardships during Aramark’s 14-year tenure, bringing home wages one worker said were “not keeping with the cost of even getting to work, let alone feeding our own families” (Gaddis, 2019, p. 1). Yet they refused to negotiate a new contract during the 2007 – 2009 financial crisis. They were terrified by all the givebacks that teachers and paraprofessionals were forced to make during their contract negotiations. So, they took a different track.

In late 2012, Cristina Cruz-Uribe, the Local 217 labor organizer, recruited a committee of workers who committed to lead the campaign. They surveyed their coworkers to determine what the negotiating priorities should be, which Gaddis and Cruz-Uribe analyzed and compiled into a report. The hundred-plus surveys told the same story: workers wanted to be able to care well for themselves and “their kids,” at home and at school. More specifically, they wanted full-time jobs that would allow them to prepare fresh, healthy, culturally appropriate meals in on-site school kitchens instead of part-time jobs reheating factory-made food shipped from Big Food companies and the district’s central production kitchen. They believed such a change would reduce food waste, improve child nutrition, and empower workers to play a greater role in the food system.

While the campaign has had peaks and valleys of activity over the past seven years, as Gaddis profiles in her book, Unite Here Local 217 has made some significant strides toward achieving this vision. The union’s 2013 labor contract expanded the number of full-time cook positions in the schools by thirty-two, while securing full labor rights for the most vulnerable group of substitute workers, raises across the board, and a commitment from the district to pilot new strategies for serving fresh and local food in the schools.

Conclusion

Democracy depends on our individual and collective willingness to leverage our education to improve the social world around us, as John Dewey reminded us more than a century ago (Dewey, 1916). Yet students and cafeteria workers rarely have the opportunity to participate in the type of civically engaged research projects described in this article. Our experiences as university-based researchers suggest that there is tremendous potential for institutions of higher education (especially those with an interest in community-based research and service-learning) to help facilitate these types of student- and worker-led research projects. We both became involved in such partnerships as graduate students and encourage other academics (at all career stages) to consider partnering with schools to make K-12 cafeterias spaces of meaningful civic engagement for kids and cooks.

Works Cited

Dewey, J. (1916). Democracy and education. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University.

Fischer, B. and Tronto, J. (1990). Toward a feminist theory of caring. In E. Abel and M. Nelson (Eds.), Circles of care: Work and identity in women’s lives. pp. 35–62. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

Gaddis, J. (2019). The labor of lunch: Why we need real food and real jobs in American public schools. Oakland, CA: University of California Press.

Glenn, E. (2010). Forced to care: Coercion and caregiving in America. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Jacobs, K. and Graham-Squire, D. (2010). Labor standards for school cafeteria workers, turnover and public program utilization. Berkeley J. Emp. & Lab. L., 31, 447.

Smedley, E. (c.1930). The school lunch: Its organization and management in Philadelphia. 2nd ed. Media, PA: self-published.

Author Bios

Melissa Terry is a mother, urban farmer, and food policy researcher at the University of Arkansas. The co-author of several publications, including the Student Food Waste Audit Guide and the World Wildlife Fund Food Waste Warriors student plate waste study, Terry loves writing logic models, working with schools, and researching case studies—so, basically, she’s a food policy nerd. Terry’s research goals are focused on researching and articulating the nexus of public policy, community engagement, social responsibility, food justice, and market-based approaches to healthy, prosperous regional food systems that nourish sustainable community wellness and economic vitality.

Jennifer Gaddis is assistant professor of Civil Society and Community Studies at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. She earned a Ph.D. in Environmental Studies from Yale University in 2014. Her research uses feminist and ecological lenses to examine the social, political, and economic organization of public school lunch programs and community-based food systems. As a transdisciplinary and action-oriented scholar, she uses ethnographic, archival, and participatory research methods to move beyond critique to envision and advocate for a politics of the possible. She is the author of The Labor of Lunch: Why We Need Real Food and Real Jobs in American Public Schools.