By. Suzie Boss, PBLWorks

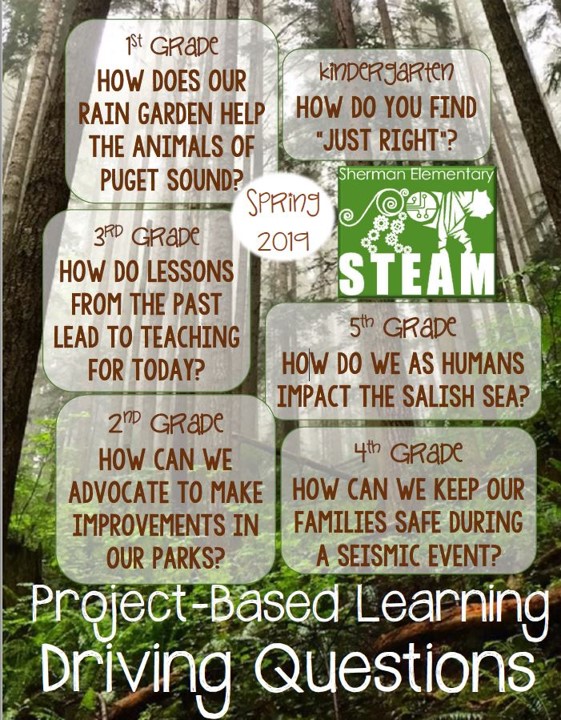

Across diverse contexts, I regularly meet students who are taking action to build a more sustainable future. Whether it’s first-graders designing a rain garden for their playground, middle schoolers educating adults about composting, or high school students advocating for investment in carbon offsets, these students aren’t waiting for “someday” to make a difference in their world.

Not so long ago, efforts like these might have been reserved for after school clubs or youth groups serving only a subset of students. That’s changing with the increasing adoption of project-based learning (PBL) as a core instructional strategy in schools around the world.

By designing sustainability projects that address academic goals, teachers are bringing real-world problem-solving right into the regular school day. As a result, more students are discovering how to use their knowledge and passion to have real impact on issues that matter to them.

Getting Started with Project-Based Learning

When teachers are new to PBL, I encourage them to learn from others who have been down this path. PBLWorks (formerly known as the Buck Institute for Education) maintains a searchable project library along with resources to help teachers design, manage, and assess high-quality PBL. EL Schools, a network of PBL schools, curates a project library called Models of Excellence. Edutopia produces video case studies that show projects from start to finish, along with blogs from PBL advocates (like me!) who share classroom-tested strategies.

For many teachers, PBL requires significant shifts in practice. It’s not the same as doing a hands-on activity like a diorama at the end of a traditional unit of study. Instead, projects that lead to deep learning challenge students to investigate open-ended questions. There’s no script or recipe. Instead, students exercise voice and choice as they apply their learning to develop solutions or products. At the end, they share evidence of their learning with an authentic audience. (Learn more in this Framework for High-Quality PBL.)

Meaning that Matters

When PBL works well, it’s often because students care about the issue or problem they are investigating. Starting with engagement is key, but students who are invested in a project also deserve to know whether their efforts have made an impact.

I remember talking with a teacher whose students tackled a water quality project in their community in Alabama. The issue was meaningful to them because it involved their favorite swimming spot. After heavy rains, runoff and trash made the water off-limits for recreation. Exploring that local problem gave students an entry point to understand the global issue of clean water, identified in the UN Sustainable Development Goals.

Students thought they were done with their project when they turned in their research reports, including an analysis of data they had collected. But their teacher challenged them to keep going by asking, “Has anything changed yet? Is the river safe for swimming after it rains? Are you just talkers,” she asked, “or doers?” That’s the push they needed to put forth an action plan and recruit community volunteers to help implement it.

To help students think about the impact of their efforts, think about these three “As” as possible outcomes: awareness, advocacy, and action. Any one of them can be a worthy end goal for a high-quality project.

Let’s consider some examples.

Awareness is about heightening understanding of an issue or a problem. In PBL, students develop expertise by investigating and researching. Once they acquire new knowledge about an issue, they are going to be motivated to enlighten others. Raising awareness might unfold through public speaking, social media campaigns, or educational events. For example, elementary students concerned about the health of fish populations created an awareness-raising campaign to keep people from dumping toxins into storm drains. They spoke to public audiences about the issue and stenciled a picture of a fish (and a “no dumping” message) next to every storm drain. Middle school students in Mumbai convinced hired drivers to stop washing their cars as a way to preserve precious water. One of their awareness-raising tools: a bumper sticker bragging about the beauty of dirty cars!

Advocacy happens when students argue for a specific solution or cause. They may speak up for the voiceless, such as an endangered species, a disenfranchised population, or a natural area that deserves protection. To be effective advocates, students must analyze issues from multiple perspectives, consider pros and cons, and make a convincing argument. High school students in my hometown of Portland, Oregon used their advocacy skills to lobby their state legislature to improve air quality near their campus, which borders an industrial area. Their argument focused on the high rates of asthma in young children—including students’ younger brothers and sisters.

Action projects enable students to put their well-researched ideas to work. I’ve watched students take action to restore watersheds, improve bike safety, start e-waste recycling programs, conduct energy audits, create habitat for bees on their school grounds, prevent food waste, and much more. Through these efforts, students not only roll up their sleeves and get to work, but often enlist others to join them. That builds their communication and leadership skills—which stay with them long after the project ends.

Sometimes, students take teachers in directions they didn’t imagine. That’s how an environmental science teacher from New York wound up in Haiti with a group of students. They started with a rigorous classroom project to develop a reforestation plan for a village that had been devastated by flooding. Sending off that detailed plan to the villagers would have been an awesome outcome—but students didn’t want to stop there. They raised funds for a service trip to Haiti and worked alongside villagers to plant 1,000 trees.

That’s the kind of experience that makes learning last.

Author Bio

Suzie Boss (@suzieboss) is an educational consultant from Portland, Oregon who has worked with schools around the globe that are shifting from traditional instruction to real-world, project-based learning. A member of the PBLWorks National Faculty, she is the co-author of 10 books, including Project Based Teaching and The Power of a Plant, co-authored by award-winning teacher Stephen Ritz.