By. John Larmer

Last spring’s experience of “emergency remote teaching” left many students feeling disengaged from their education. Removed from their classrooms and classmates and missing face-to-face interaction with teachers, it was hard to find the motivation to listen to lectures on Zoom, complete online worksheets, and do textbook assignments. In some cases, points or grades – traditional motivators for student participation – weren’t being used, adding to the problem.

Of course, this was true only for those students who had the appropriate technology, access to online learning, and the time, space, and support for doing schoolwork at home. Those who didn’t were denied an equitable opportunity to learn and they struggled; some even checked out of school entirely. And for many Black and brown students, virtual schooling was even more disengaging than usual.

However, schools and teachers who used project-based learning (PBL) told a different story.

Students who experienced high-quality PBL last spring stayed engaged and kept learning. If they and their teachers were used to working in a PBL environment, moving it online proved, if not seamless, at least doable. Many were already familiar with using technology tools and working independently without constant teacher direction. If teachers tried PBL for the first time when schools shifted to remote learning, it felt like a brave step and a challenge at first, but they and their students found that it worked.

Why does PBL work well for remote learning? Let me count the ways:

- Projects that are authentic to real-world issues and relevant to students’ lives are inherently motivating. A pandemic provides many opportunities for such projects – as does our nation’s current attention to issues of racial justice. Students are more likely to stick with an engaging project than complete traditional assignments and lessons delivered online.

- In PBL, the teacher doesn’t control everything that goes on in the classroom; the culture emphasizes independent student work time, collaboration with a team, and inquiry guided by students’ questions. This translates well to at-home learning where the teacher (much less a parent or a caregiver who needs to work) isn’t able to observe and guide students as frequently as in a brick-and-mortar classroom.

- One of the key aspects of authenticity in PBL is a connection with audiences, experts, and organizations beyond the classroom. Students working on projects at home, already working online and using technology tools for communication and collaboration, find it easier and more natural to make these connections than in a traditional school setting.

What Does PBL Via Remote Learning Look Like?

To illustrate the above points, here are three examples of projects that were done effectively via remote learning last spring.

1) In Boulder, Colorado, middle school teacher Kelly Reseigh facilitated the “Making Space for Change” project (from the PBLWorks project library), which focuses on environmental sustainability. Students assisted their local town council in designing and locating eco-friendly public spaces in the community.

Students used a Twitter hashtag to share their progress with stakeholders, met in Zoom breakout rooms to engage in peer critique protocols at key stages, and reflected on how they were doing with remote learning via videos on Flipgrid. Kelly met with the whole class on Zoom twice a week and held virtual office hours to check in with student teams, who scheduled their own work time. Students presented their work in a virtual town hall meeting with local officials and experts. You can read more about how she managed the project in this blog post.

2) In Manchester, New Hampshire, ESL teacher Liz Leone did a remote-learning project called “Happy Plants” with her fourth- and fifth-graders, who were newcomers to the U.S. and just beginning to learn English. The goal was for students to learn some science by growing plants in a pot at home and testing variables like soil, light, and water.

Liz launched the project with a virtual “field trip” where she recorded herself talking with a local farmer. She addressed equity issues by making home doorstep deliveries of supplies to students who needed them and provided low-tech options for communicating via mobile phone. Her technology tools included Google Suites, Prezi, Newsela, Mystery Science, and YouTube, among others.

3) High school students in Massachusetts and Iowa collaborated on a remote-learning project focused on natural resources and uncontacted Indigenous people. Students were challenged to find and measure illegal gold mines in the Yanomami territory of the Amazon using high-resolution satellite imagery via an online tool called Earthrise Education. They sent their geospatial data to the authors of a groundbreaking news story published by Reuters and Survival International, which has already garnered over three million views.

Technology Tools to Support High-Quality PBL Online

Here are some technology tools used by teachers to help manage PBL online:

For individual and group meetings

Whole class, project team, and one-on-one meetings can be done with Webex, Google Meet, Zoom, and Whereby.

For white boards and brainstorming

Mural and Explain Everything are virtual white boards that can be used not only for targeted instruction, but are also fantastic for remote brainstorming and problem ideation.

For student project management

Trello is an example of a tool that can help students keep track of project action items and then share them with their project teams – a valuable skill students need to master regardless of context.

For customized online instruction

Nearpod can be used to create customized online instruction that targets the individual needs of each student.

For younger students

K-2 teachers can use SeeSaw for students to view and respond to lessons. Teachers can provide feedback on student work in the application, too.

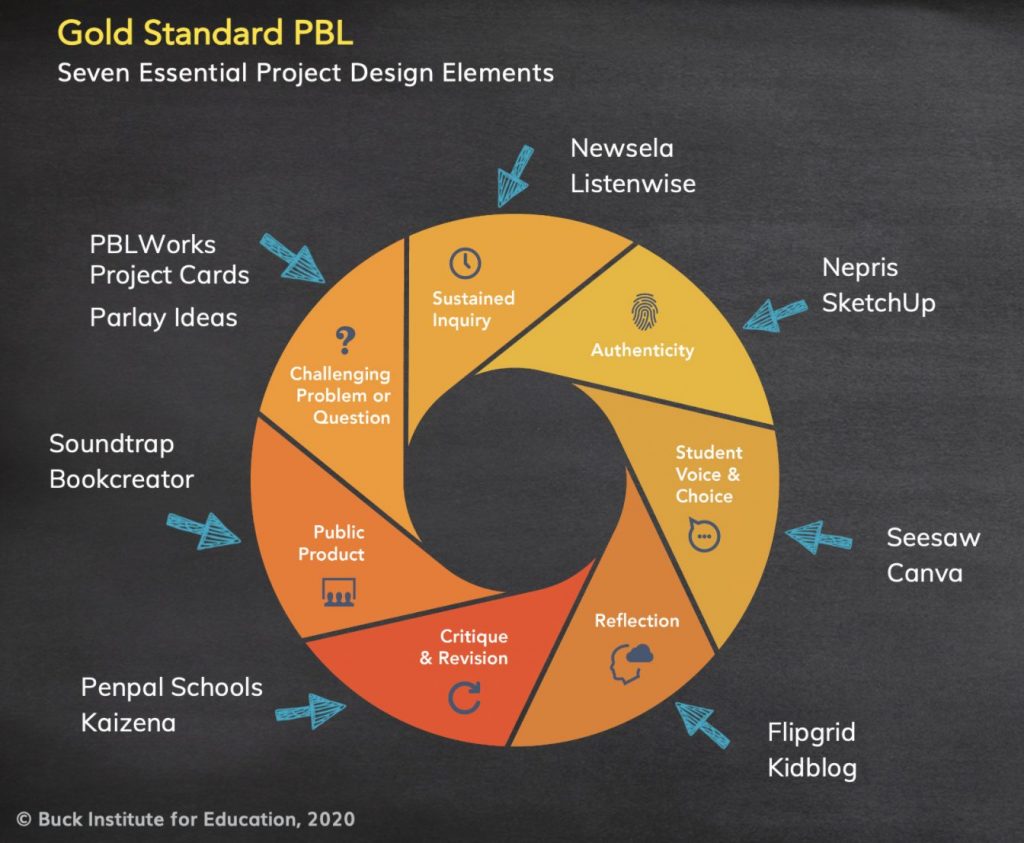

The image below shows the seven Essential Project Design Elements in PBLWorks’ model for Gold Standard PBL, with additional technology tools that support each element.

Low-Tech PBL Strategies

If your students don’t have access to technology or the Internet, consider these strategies for PBL:

- Offer activities that are engaging, hands-on, and contribute to larger project goals, such as collecting data or taking part in a daily “get outside” mindfulness observation routine.

- Ask students to prototype designs for project products with whatever materials they have available. They can also write proposals for solutions to problems, rather than make digital products or online presentations.

- Have students interview family members and neighbors or make phone calls to distant people to get additional expertise and feedback for prototyping or proposal writing.

- Use art, cooking, building and construction, and the outdoors as resources. As teacher Kay Sturm advises, “give students the chance to ‘explore’ through the lens of the learning you set up for them.”

- Ask students to do an individual project where they pick a topic of interest, explore it on their own (e.g., family history, the physics of baseball or skateboarding, the science of cooking), and create a written product or use a mobile phone to create videos or podcasts.

I’ll conclude with some general advice we’ve heard from teachers for using PBL in remote learning. Pay attention to your students’ social-emotional needs; they miss each other and their teachers. Help students practice the self-management skills they’ll need for doing projects at home. To make it easier on yourself during these trying times, consider adapting an existing project like one of these or one of these rather than designing your own from scratch.

And finally, cut yourself some slack. You’re going to make mistakes (but learn from them), encounter technology troubles, and feel like what you’re doing isn’t enough or as good as it was in the classroom.

But go for it anyway. Don’t revert to disengaging traditional instruction, even if it might seem easier to do online. Your students will enjoy learning and gain much more by doing meaningful projects. PBL can provide them with ways to process what they’re going through, express their emotions and ideas, and feel like they’re making a contribution to the pressing problems of our communities and our world today.

Author Bio

John Larmer is editor-in-chief at PBLWorks (the new brand name of the Buck Institute for Education), where he oversees its written materials and manages its PBL Blog. He wrote and edited the PBL Toolkit Series of books, rubrics for 21st century success skills, and other materials for PBL teachers. He contributes to the creation of PBLWorks’ professional development programs and online project library. In 2015, John co-authored Setting the Standard for Project Based Learning, co-published by ASCD, and in 2018 contributed to and edited Project Based Teaching, also co-published by ASCD. For ten years, John taught high school social studies and English and co-founded a restructured small high school. He was a member of the National School Reform Faculty and school coach for the Coalition of Essential Schools.