Joel Tolman and Amy Champagne, Common Ground High School (New Haven, Connecticut)

This is the third blog in a Q&A blog series that features GSNN partners describing best practices and lessons learned on topics tied to each of the impact systems in the GreenPrint. This Q&A focuses on the Curriculum and Instruction system.

Discuss why it is important for leaders, teachers, and students to co-create curriculum and learning experiences at Common Ground.

Different members of our school communities all have something critical to contribute:

- Teachers know what works for their students and content – and in our experience teach much more effectively when they’ve had a central role in designing their curricula.

- School leaders and curriculum developers can help to create a curriculum with coherence and make sure it actually gets written down!

- Students are the most qualified to talk about what is and isn’t working for them, what matters to them, and where they want their education to take them.

- Families know their children better than we ever will as educators and are deeply invested in these young people’s success.

- Our communities are full of people with knowledge and skills complementary to those of our teachers.

Why wouldn’t these people work together to design classes, projects, and whole schools?

Describe some of the structures Common Ground has in place to facilitate the co-creation and implementation of curriculum for health, equity, and sustainability.

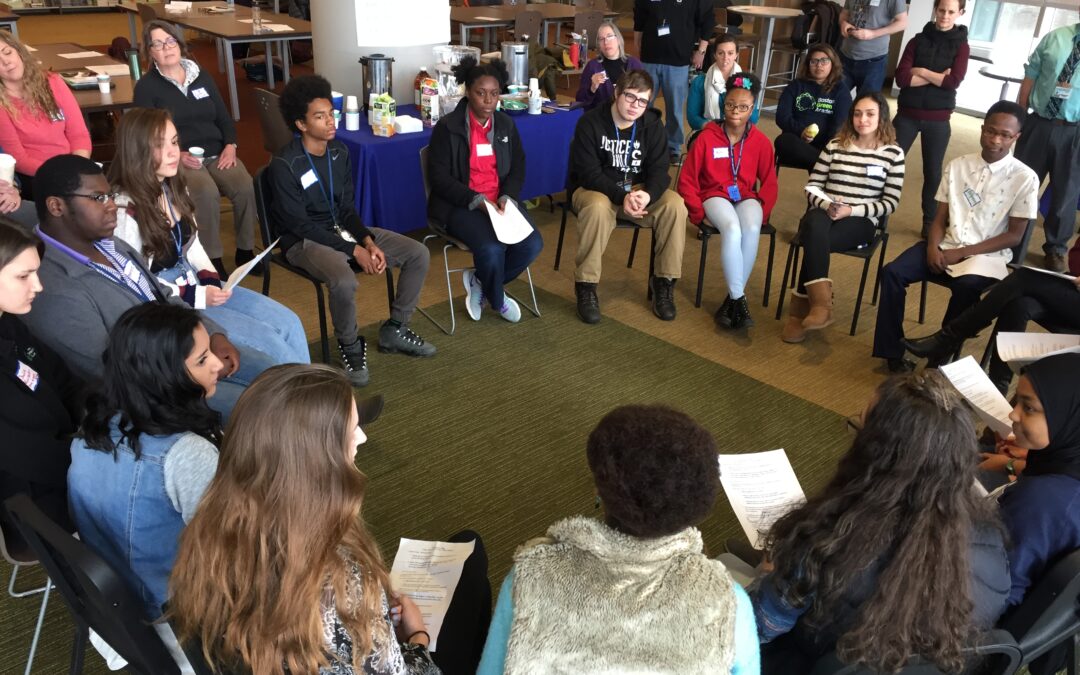

Sometimes, students need a space of their own to talk through what they want from their education. We often use youth-only spaces or fishbowl-style conversations to center young people’s voices. For instance, in 2016, some of our students worked with Hiram Rivera – at the time the Executive Director of the Philadelphia Student Union – to lead discussions in our advisory groups. They asked teachers to leave and then had an honest conversation: What do you expect from your Common Ground education? Are you getting what you expect? What needs to change? Student facilitators presented the results to our teachers and kicked off a process that changed the experience of every student who came after them.

Sometimes, students need a space of their own to talk through what they want from their education. We often use youth-only spaces or fishbowl-style conversations to center young people’s voices. For instance, in 2016, some of our students worked with Hiram Rivera – at the time the Executive Director of the Philadelphia Student Union – to lead discussions in our advisory groups. They asked teachers to leave and then had an honest conversation: What do you expect from your Common Ground education? Are you getting what you expect? What needs to change? Student facilitators presented the results to our teachers and kicked off a process that changed the experience of every student who came after them.

Sometimes educators need their own space too. There have definitely been moments when our teachers kicked everyone else out of the room so that they could move from divergent to convergent thinking, and make sure they were ready to teach when class began. As teachers, we benefit from templates, principles, and rubrics that we use to vet our work, as well as timelines, processes, and partnerships with people with other points of view (even when it’s hard for us to share space). But, at the end of the day, we have a responsibility for putting these classes into action, so we need agency and accountability.

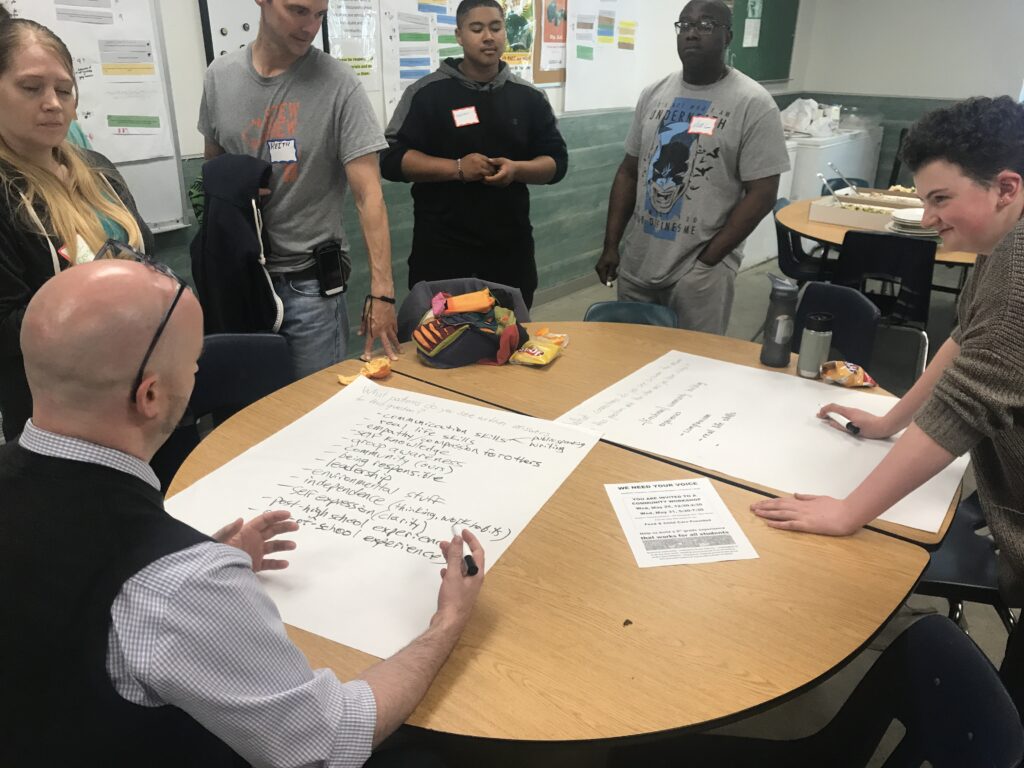

While spaces that center young people and teachers are valuable, something magical happens when students, families, community members, and professional educators sit down to create learning experiences together. When we were building our ninth- and tenth-grade interdisciplinary core curricula, we held evening design workshops in our cafeteria. We’d already surveyed students, teachers, families, and community members about what they thought was most critical, and the data were posted on the walls. We sat down with soul food from a local restaurant and salad from our urban farm and built units together on flipchart paper. These magic marker unit plans weren’t ready to teach at the end of the evening, but they contained the essentials: big questions, key field experiences, disciplinary connections, and culminating products and performances.

In several recent summers, Common Ground brought together teams of teachers, school leaders, and students to build and rebuild courses. We spent between two days and a week in a consciously co-creative space – moving between small design teams, peer-to-peer consultations, opportunities to reflect while hiking in the woods, shared meals, student fishbowls, content workshops, and final exhibitions of what we’d created. Everyone involved was compensated for their time. Some pretty great courses and interdisciplinary projects have emerged from these summer institutes!

One question we face is how to keep up co-creative energy once a learning experience has been taught a couple of times. If co-creation is a one-time thing and your curriculum doesn’t change to reflect changes in the world, your students, and your community, its relevance will fade!

Common Ground takes a “city as a classroom” approach to foster learning beyond the four walls of the school building. Discuss some of the ways in which educators bring the community into the classroom and students into the community.

Sometimes, it’s about bringing the city into the school. Right now, our tenth-graders are deep in a unit on climate justice. The unit launched with a chance to meet a bunch of climate changemakers from New Haven – the City Engineer and City Architect, a recent college grad who’s working in climate policy, and two high school students who are taking on paid roles as climate health education fellows. Students learn about different approaches to community changemaking and see which is the best fit for them. As students develop a deeper understanding of climate change, they start working with community-based artists to create public art that shares what they’re learning. They’ll share their artwork, persuasive speeches, and other culminating work at a rally on our campus, with community members in attendance.

Other times, it’s about getting students out into the city. This can mean scavenger hunts, walking surveys of urban waters, or toxic tours of environmental justice challenges. Students can interview neighbors, gather data on urban environmental issues, and then use that information to create real products. At its best, students are growing into scientists and historians. We’re inspired by Nataliya Braginsky, who works at Metropolitan Business Academy, another New Haven school. Her students have created amazing online walking tours of Black, Latinx, and Indigenous history in New Haven – what a powerful example of real work for real audiences!

Other times, it’s about getting students out into the city. This can mean scavenger hunts, walking surveys of urban waters, or toxic tours of environmental justice challenges. Students can interview neighbors, gather data on urban environmental issues, and then use that information to create real products. At its best, students are growing into scientists and historians. We’re inspired by Nataliya Braginsky, who works at Metropolitan Business Academy, another New Haven school. Her students have created amazing online walking tours of Black, Latinx, and Indigenous history in New Haven – what a powerful example of real work for real audiences!

Educators often need to build their competence navigating the cities their students call home, too. One thing that can be helpful is to scan the assets and problems, natural and social, in the area around your school. We learned this practice from Akiima Price, a Washington, D.C.-based educator who uses nature as the context to create change in urban communities of color.

When you start to map your local environment, what you find can be pretty amazing. Lots of people look at Common Ground’s campus – an urban farm, on the edge of a state park, within city limits – and think, “that’s nice, but my school doesn’t have all that.” But some of the richest learning opportunities have nothing to do with those things. Common Ground’s neighborhood includes a state university where students can take free early college classes. It includes two K-8 schools where students can steward gardens and tutor kids. There’s the capped landfill for the town next door, turned into a solar farm and transfer station – which raises so many questions about why our neighbors bring their trash into our city. There’s the Woodin Street Cemetery, where the city interred 1,000+ people whose families couldn’t afford burial expenses. There’s the largest concentration of public housing in the city, which until a few years ago was fenced off from access to the town next door. There’s a beautiful brook, with persistent challenges related to flooding, illegal dumping, e. coli, and fecal coliform. There are neighbors who know how to organize, who work in energy efficiency, and who are nurses and public health professionals. It’s amazing to have a farm and a park in our backyard – but these other challenges and assets are just as rich! What’s directly around your school?

Students have voice and choice in their learning at Common Ground. What are some lessons you have learned over the years when it comes to implementing a culture of student-centered learning?

Real roles and rights for students are foundational building blocks of teaching and learning at Common Ground. They’re also areas of growth for us! At the end of every semester, students take a survey in each of their courses, so that their teachers can hear from them what is and isn’t working. Students designed this survey and one of the questions asks, “In this class, were you able to make choices, raise your voice, and grow as a leader?” This fall, about 7 in 10 students said yes to this question. Another 24% weren’t sure or felt neutrally.

So, again, we have room for growth! And there are some things we think make a difference:

- When possible, students should get paid for raising their voices. Their contributions have real value and compensating them keeps leadership from being limited to young people who have the privilege to volunteer. If a paycheck isn’t possible, students can earn academic credit or community service hours for their changemaking work.

- Different students respond to different opportunities. We have an amazing group of Student Culture Creators who just partnered with staff to plan the most meaningful celebration of Black History Month in Common Ground’s history. Some students show up for Student Leadership Team – our version of student government, which is open to anyone (not just elective representatives), meets after school, and awards community service hours. Other students want to raise their voices by starting after-school programs, writing grants, or taking on paid green jobs. Students should open any door in the school and find an opportunity to make choices and raise their voices.

- A big question is how you center the needs and experiences of young people who are on the margins of your school community. We learned an amazing practice from Barbara Crock, who works with high schools to help them transform into places that actually work for young people. You identify the students who are most on the margins – who just got back from suspension, who failed five classes last semester, who are behind a grade. You have a one-on-one conversation about a design challenge your school is facing. Then you call up their families, say you just had a great conversation with their kid, and ask for their advice on the same challenge. Then, if you can, you invite them to be part of a design conversation. What a brilliant idea!

Joel Tolman (Director of Impact and Engagement) and Amy Champagne (Director of Curriculum and Instruction) have worked together at Common Ground for more than 15 years. For more information about Common Ground, visit www.commongroundct.org. For more information about work to root urban public schools in their urban environment, visit www.teachcity.org.