By. Reid Bogert

Twenty-three school districts serve over 130 schools in San Mateo County. From a watershed standpoint, these are interesting numbers. Why? School campuses contain a significant amount of impervious landscape, such as paved playgrounds, parking lots, plazas, and corridors. These smooth, open surfaces are essential for safety and practicability when it comes to navigating campus and in emergencies. Yet, this typical campus layout poses several environmental challenges.

From a surface water perspective, all that asphalt and paving can lead to significant runoff when it rains. In San Mateo County, the storm drain system is a separate network of gutters, pipes, and other drainage features that ultimately connect to creeks, the Pacific Ocean, and San Francisco Bay without any form of treatment. For the most part, rain water at schools drains to inlets that flow out to adjacent streets, uncleaned and unmanaged. The issue of trash is exacerbated when haphazardly discarded straws, plastic baggies, and other single-use items are flushed into the storm system. The extra runoff flowing from schools can also add to localized flooding and creek erosion during big storms, as well as campus flooding itself.

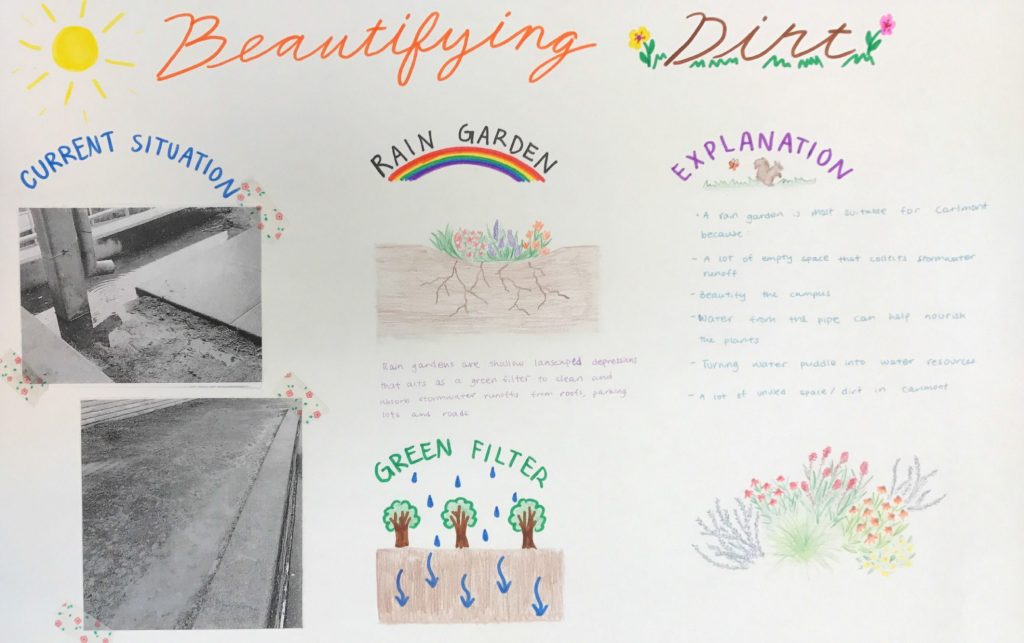

Beyond thinking about water and water pollution, what about student and teacher comfort? All those paved surfaces can get seriously hot and uncomfortable for students playing and learning outdoors. A barren, hot playground, without shade from trees and dynamic play areas to explore, is likely the last place students want to go for refuge when it’s time for recess, lunch, or an outdoor lesson. Green infrastructure at schools can play a pivotal role in addressing cooling and comfort needs, as well as pollution prevention. For example, simply adding trees along the peripheries of playgrounds or adjacent to buildings can be an easy way to create shade and capture rain water that might otherwise become a nuisance. Other green infrastructure options, like rain gardens, can capture, store, and clean runoff – with the added benefits of recharging groundwater and reducing runoff going down storm drains.

The need for change and to green up campuses is starting to sink in, and San Mateo County is already seeing this transformation unfold. Schools across the country are looking for ways to adapt to extreme conditions, such as high heat days, drought, increased stormwater volumes, and more frequent storms during the wet season. Many schools now see the need to act as community resilience hubs and emergency centers during natural disasters, like wildfires and floods, and public health crises, like COVID-19.

The San Mateo Countywide Water Pollution Prevention Program (Stormwater Program), a program of the City/County Association of Governments of San Mateo County (C/CAG), has partnered with local schools and school districts, with support from the San Mateo County Office of Education, to bring schools into the fold of sustainable watershed management and to broaden K-12 environmental literacy on the topic of using rain water as a resource.

The idea is to work rainwater resiliency into schools at different scales to maximize the benefits for students, teachers, communities, and the environment.

The first scale, which is really the foundation, is to introduce stormwater and water pollution prevention curriculum into schools at a variety of grade levels. There are many ways to do this, and the Stormwater Program has experimented with a few. School engagement started years ago and has evolved from musical acts at school assemblies, to Jeopardy-style high school presentations, to high school green infrastructure project concept contests, to a professional development program aimed at reaching more teachers and increasing the longevity of curricular components.

Recognizing the need to institutionalize watershed education, the Stormwater Program recently expanded its focus on curriculum and now partners with the Office of Education’s Environmental Literacy Program to fund and co-lead a paid teacher fellowship for K-12 teachers focused on sustainable watersheds. Two years into this environmental literacy professional development program, 20 teachers from a variety of schools around the county have generated standards-aligned unit plans focused on water scarcity, wastewater management, watershed systems, climate change, drought, and stormwater engineering and community-based solutions. Stormwater Program staff have gone into classes to help teach core concepts and as part of the 2020 program, recently supported teachers with planning and installing a rain barrel and a cistern at two schools. Not only are students learning how to manage rain water as a resource and protect water resources, but schools are now becoming places to advance infrastructure solutions.

The hope with these environmental literacy program connections is that with more engaged teachers, we will encourage site-based champions to lead additional projects and gain support and enthusiasm from administrators and facilities staff.

This gets to the next scale of engagement and implementation – the site scale. As an early adopter, Tierra Linda Middle School in San Carlos installed a rain barrel system adjacent to the administration office. The school’s Green Team, led by teachers and students interested in environmental issues, sought donations to create a rain garden, now fed by two daisy-chained rain barrels (donated by the Stormwater Program), which collect runoff from building’s rooftop. The project installation doubled as a community engagement event (pre-COVID-19), complete with a bike smoothie blender!

The third scale of sustainable stormwater at San Mateo County schools is at the street level. Much can be done in the street right-of-way to better manage stormwater flows and rethink the design and purpose of streets for enhanced comfort and safety. In 2017, C/CAG funded ten integrated Safe Routes to School and Green Streets Infrastructure Pilot Projects throughout the county. These projects focus on improving pedestrian safety through integrated infrastructure with vegetated curb extensions that treat stormwater, shorten crossing distances, improve bike and pedestrian visibility, and beautify the streetscape. Eight of ten projects are complete. This pilot program links with a broader effort by C/CAG to develop a Countywide Sustainable Streets Master Plan, which identifies and prioritizes planned and newly identified active transportation projects (like Safe Routes to School projects) with good opportunities for integrating green infrastructure.

Finally, at the watershed scale, schools represent a largely overlooked opportunity in San Mateo County to capture and retain stormwater from significant upstream areas, such as through large retention structures under playing fields or parking lots. C/CAG is working on a new planning project to identify and prioritize regional scale multi-benefit stormwater capture projects and is hoping to leverage partnerships with schools. These projects can offer win-win solutions for achieving municipal stormwater management goals and for schools looking to upgrade campus lots and structures with new athletic fields, nature-based play areas, and playgrounds. These larger projects could potentially leverage school bond funds for campus improvements and engage community partners to support other water and climate resiliency initiatives that offer excellent learning opportunities. Attaching a large cistern to a building in connection with other campus improvements, for example, can create a new learning tool, reduce stormwater runoff impacts, and meaningfully offset potable water use for irrigation during dry months.

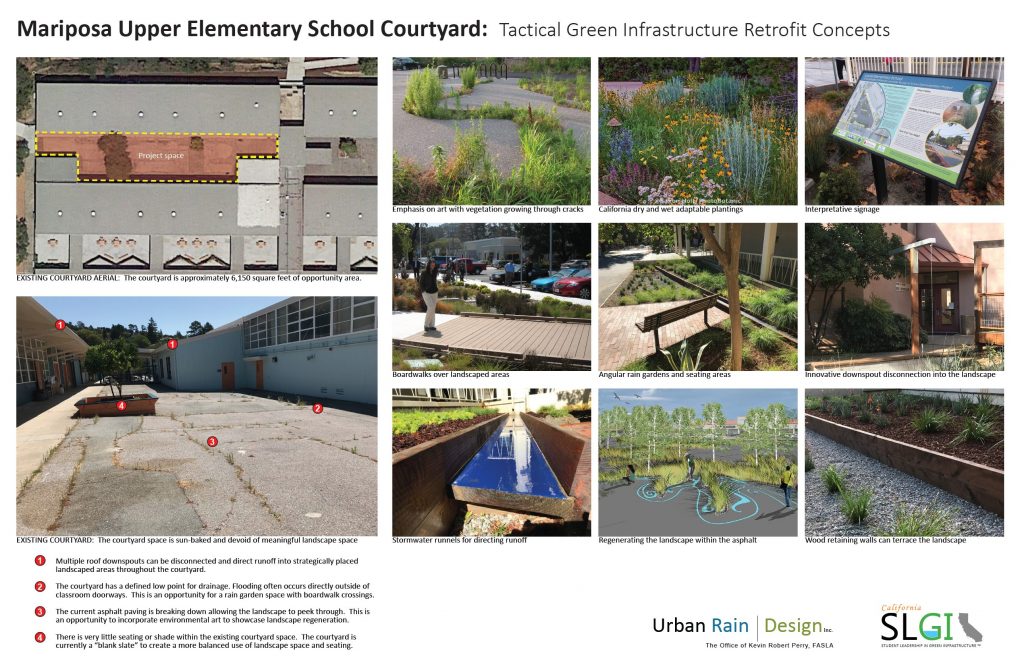

From problem-based learning across core curricula areas, to on-site projects like rain barrels and rain gardens, San Mateo County schools are adding rain water as a resource to the mix of campus activities and teaching tools. The Stormwater Program is excited to continue this evolving work, and there’s more on the horizon. With recently awarded funds from the Bay Area Council’s California Resilience Challenge Grant and C/CAG, the San Carlos School District and other local partners plan to have a series of campus-wide schoolyard greening concept plans on-tap for next year. These concepts will help district schools advance from ideation to implementation. They will also help schools adapt to the impacts of climate change and the constraints and safety concerns of a global pandemic. Project components may include rainwater resiliency features, such as cisterns, rain barrels, rain gardens, and bioretention swales, linked with outdoor classroom designs and learning opportunities. With a focus on collaboration and multi-benefit outcomes, we are exploring all options to make rain water work for schools across San Mateo County!

Author Bio

Reid Bogert is the Stormwater Program Specialist for the San Mateo Countywide Water Pollution Prevention Program. Reid supports San Mateo agencies in complying with the Municipal Regional Permit and has spearheaded partnerships and engagement with San Mateo County schools to advance water resiliency and stormwater curriculum and infrastructure goals. Reid comes from a background in sustainability and conservation and has worked on stormwater programs in the Bay Area and in Chicago, where he completed his master’s in environmental science and policy from the University of Chicago.