By. Heather Cunningham, Ph.D.

This past summer, many people in the U.S. and worldwide became more aware of the grave injustices Black Americans face on a daily basis. This awakening has led many educators to ask themselves, “What can I do personally to make my practice more responsive to Black and Brown students?” One step that all K-12 educators can take is enacting a thoughtful upgrade of their classroom management practices.

Classroom Management and Systemic Racism

Goal Four of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals challenges us to provide an inclusive and equitable quality education for all students:

“Education liberates the intellect, unlocks the imagination and is fundamental for self-respect. It is the key to prosperity and opens a world of opportunities, making it possible for each of us to contribute to a progressive, healthy society.” (The Global Goals for Sustainable Development, n.d.)

However, for students to receive the life-altering benefits of education, they must be present in the classroom. And data suggests that Black and Brown students in the United States are suspended and expelled from school at much higher rates than their White peers. Consider the discipline data collected by the federal government about my hometown, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Black students in Pittsburgh and many other areas across the nation are suspended and expelled at disproportionate rates. Why is that?

One deep root that explains this disparity is that the dominant discipline model used in U.S. schools is a punitive discipline system. Punitive discipline is based on the Western legal tradition and relies on the punishment of individuals who engage in unwanted, “different,” or offensive behavior as defined by a classroom teacher, school leader, or officials in the broader school system. Typically, unwanted or offensive behavior is codified by a school discipline code. Exclusion (detention, suspension, expulsion) is the typical punishment in the U.S. when students engage in behavior deemed offensive by school discipline code.

Research studies have found that students of color and students from lower socioeconomic backgrounds receive more disciplinary referrals from teachers. Skiba et al. (2002) conducted a study in 19 middle schools located in a large, urban, midwestern public school district. They found “a differential pattern of treatment, originating at the classroom level, wherein African American students are referred to the office for infractions that are more subjective in interpretation” (p. 317). They share that White student referrals tended to be for more objective reasons such as “tardiness” or “fighting,” and Black students were referred for subjective reasons such as “talking back,” “mouthing off” to a teacher, being “disrespectful,” or “rude.” These subjective reasons for which Black students are sent out of class may be deeply rooted in the systemic racism that pervades the U.S. education system. Namely, they could be sent to the office based on culturally-based expectations White teachers may have for student behavior, and the unconscious biases and prejudices that many White teachers may possess and must work to overcome.

Educators who want to work against the systemic racism found in their school’s punitive discipline system can consider a different framework for classroom management and building school culture. Using practices rooted in restorative discipline is a promising way to do this. Restorative discipline is an approach to classroom management rooted in restorative justice philosophy. This philosophy advocates that schools should be places where young people are able to make mistakes, reflect upon and learn from these mistakes, and correct them as they continue to learn and grow. In terms of academics, U.S. schools have embraced this growth mindset idea. Students are expected to make mistakes on assignments, receive feedback from their teachers, learn from their errors, and continue to grow.

Restorative discipline uses this same approach to address student behavior. In this case, a student whose behavior harms themselves or others should be moved toward the support structures that can help them make better future choices instead of sent out of school through suspension or expulsion (Schiff, 2013). Through restorative discipline, students are given the opportunity to reflect upon and grow from errors in judgement and conflicts without necessarily being sent out of the classroom for disciplinary action. They are treated as responsible, yet imperfect community members.

Methods Associated with Restorative Discipline

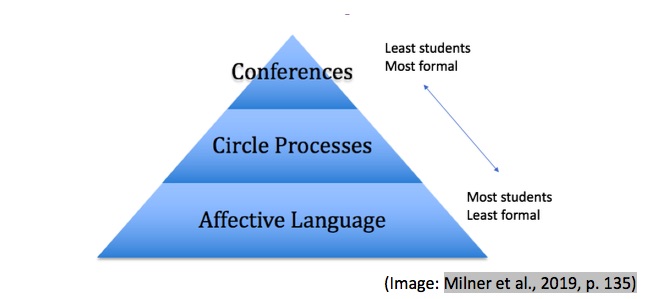

Three methods associated with restorative discipline include affective language, circle processes, and restorative conferences. Each are described below.

Affective Language

Affective language is the least formal classroom management strategy and can be used with the greatest number of students throughout the day. It requires no preparation, only the formation of new communication habits on the part of the educator. Affective language includes foundational interactions between educators and students that can be used in an on-going and seamless way in classrooms and school environments and serve as reminders to students that they are part of a community at school. Affective language can be either statements or questions that express feelings related to behaviors or actions of others (Costello, Wachtel, and Wachtel, 2009). This language encourages students to self-correct their own behavior before small problems become large ones that need disciplinary action. Affective language can affirm positive behavior and re-direct unwanted behavior. Affective statements help students understand how their actions impact others (San Francisco Unified School District Restorative Practices Office, n.d.). For example, a teacher might say, “James, I am very upset that you ripped pages out of your library book. When you rip the pages out, other students cannot enjoy the book after you.” Affective questions prompt students to reflect on how their actions impact others and consider how to resolve conflicts (Costello, Wachtel, and Wachtel, 2009). A teacher asking affective questions might say, “What were you thinking when you took Mia’s snack off her desk? How do you think she has been affected? What do you think you need to do now to make things right?” Student responses to these questions allow them to take responsibility and make things right – without being sent to the office.

Overall, affective statements and questions can promote a classroom and school culture that support self-awareness of students’ actions, help students become more aware of how their actions affect others, and promote a sense of community among learners. Using affective language can improve classroom management, as students develop a sense of themselves as class community members who can contribute to the group in positive ways while growing in their abilities to manage their own distracting behaviors.

Circle Processes

A circle process is a group process that can be used to strengthen relationships, discuss issues that impact school community members, or resolve interpersonal conflicts. This process can be used proactively as part of daily classroom and school routines and reactively to solve problems. Use of a circle process in a classroom or school setting may require some planning on the part of educators, and typically doesn’t involve a group larger than one classroom of students.

To enact a circle process, Amstutz and Mullet (2005) suggest an educator and students move through the following steps:

- Students sit in chairs in a physical circle and a facilitator leads the meeting (typically an educator, could be a student).

- The facilitator makes an introduction and reminds students of the values embodied in the circle process. Common values expressed include that everyone in the circle is connected by core values but that each person has a right to his or her individual beliefs, accountability, honesty, responsibility, and compassion.

- The facilitator poses a question or topic to the group and then passes a talking piece.

- Circle participants can only talk when holding the talking piece and only one person can talk at a time.

- Participants can pass the talking piece if they don’t want to talk.

- The facilitator opens and closes the circle process.

Used as an ongoing feature of daily life in a classroom, circle processes have the potential to build community among students and educators and solve problems. Through this process, educators and students can collaborate to identify underlying problems that give way to undesired behaviors, promote student accountability for actions, and allow for creative community responses to problems or conflicts. Educators who use circle processes will find that their role shifts from rule enforcer to facilitator and that students develop greater awareness of how their actions impact others. These meaningful shifts transform the culture of the classroom and school to one that more closely resembles a community – where problems are solved together, without sending students out of class to the office for discipline.

Restorative Conferences

Restorative conferences can be used as a tool when relationships have been broken and are in need of rebuilding, when serious harms have been committed, or when a student is exhibiting signs of personal crisis and may need support. Restorative conferences typically involve only the affected parties, school personnel, and in some cases, family members of involved students. Facilitators use open-ended and student-centered questions that prompt students to talk and restore broken relationships. Restorative conferences take the most amount of planning of the three restorative discipline methods and involve the fewest students at one time.

Restorative conferences afford students the opportunity to meet face-to-face with other students or educators and discuss what happened and why, how each person feels, how to make things right again, and how to avoid a similar situation in the future (Amstutz and Mullet, 2005). Some questions that might be asked in restorative conferences include (Davidson, 2014):

- Tell me what happened. What was your part in what happened?

- What were you thinking at the time?

- How were you feeling at the time?

- Who else was affected by this?

- What have been your thoughts since?

- What are your thoughts now?

- How are you feeling now?

- What do you need to do to make things right? Repair the harm that was done? Get past this and move on?

- What can we do to support you?

- What might you do differently when this happens again?

Some keys to success for restorative conferences include voluntary participation, responsible students acknowledging actions before meeting with those harmed, harm acknowledged by all during the conference, parties discussing how to make things right again, and parties signing an agreement with steps to avoid future harms (Zehr, 2015). Of course, restorative conferences will not eliminate all conflicts between students, or students and educators, but they do allow students to explain their part in what happened and have a voice in how the situation is resolved. This allows them to maintain their standing as school community members instead of being cast out through an exclusionary practice such as suspension or expulsion.

Restorative discipline holds the promise of delivering more responsive and just discipline outcomes to Black and Brown students. This is because it promotes their development within the school community instead of exposing them to the systemic racism inherent in punitive discipline systems which frequently exclude them from the school community. In choosing to use restorative discipline methods in their classrooms or schools, educators are indeed moving toward achieving Global Goal Four: providing inclusive and equitable quality education for all students.

References

Amstutz, L. and Mullet, J. (2005). The little book of restorative discipline for schools: Teaching responsibility; creating caring climates. New York, NY: Good Books.

Costello, B., Wachtel, J., and Wachtel, T. (2009). The restorative practices handbook for teachers, disciplinarians and administrators. Bethlehem, PA: International Institute for Restorative Practices.

Davidson, J. (2014). Restoring justice. Teaching Tolerance, 47. Retrieved from: http://www.tolerance.org/magazine/number-47-summer-2014/feature/restoring-justice

The Global Goals for Sustainable Development. (n.d.). Quality education. Retrieved from: https://www.globalgoals.org/4-quality-education

Milner, H., Cunningham, H., Delale-O’Connor, L., and Kestenberg, E. (2019). These kids are out of control: Why we must reimagine “classroom management” for equity. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

San Francisco Unified School District Restorative Practices Office. (n.d.). Restorative practices: Curriculum and supporting documents. Retrieved from: https://www.healthiersf.org/RestorativePractices/Resources/index.php

Schiff, M. (2013). Dignity, disparity, and desistance: Effective restorative justice strategies to plug the “school-to-prison pipeline,” presented at the Closing the School Discipline Gap Conference, Washington, D.C., 2013. Los Angeles, CA: The Civil Rights Project. Retrieved from: https://www.civilrightsproject.ucla.edu/resources/projects/center-for-civil-rights-remedies/school-to-prison-folder/state-reports/dignity-disparity-and-desistance-effective-restorative-justice-strategies-to-plug-the-201cschool-to-prison-pipeline

Skiba, R., Michael, R., Nardo, A., and Peterson, R. (2002). The color of discipline: Sources of racial and gender disproportionality in school punishment. Urban Review, 34, 317–342.

Zehr, H. (2015). The little book of restorative justice. New York, NY: Good Books.

Author Bio

Heather Cunningham is an Assistant Professor of Education at Chatham University in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Before earning her Ph.D. in Instruction and Learning, Heather was a K-12 public school teacher in Washington, D.C. and downtown Pittsburgh for 13 years. She has also worked in education internationally in Honduras, the Dominican Republic, and Malawi. Heather is co-author of the book These Kids are Out of Control: Why We Must Reimagine “Classroom Management” for Equity. Her work centers on preparing teachers to support K-12 students who are marginalized by race, poverty, and language, and examining K-12 education within a framework of global sustainability.