By. Christina Hecht, PhD, Senior Policy Advisor, Nutrition Policy Institute, University of California, Division of Agriculture and Natural Resources

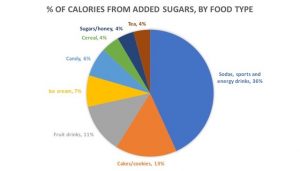

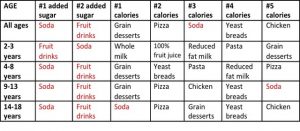

Hydration is essential for keeping kids’ (and adults’) bodies functioning at their best – but too many reach for a sugar-sweetened beverage (SSB) when they are thirsty. SSBs are a major source of calories in the American diet. In fact, for American youths aged 14-18, SSBs are the top single source of calories. Those calories come from sugars in these sweetened beverages. Across all ages, SSBs are the largest single source of added sugars in the American diet (Reedy).

Pie chart based on data in “Usual Intake of Added Sugars: Added Sugars: Means, percentiles and standard errors of usual intake, 2007-2010.” National Cancer Institute Website.

Table developed from data in “Dietary sources of energy, solid fats, and added sugars among children and adolescents in the United States,” J. Reedy and S. Krebs-Smith. J Am Diet Assoc. 2010; 110: 1477–1484.

This is why there is a growing movement to promote water as “First for Thirst.” Cutting out excess calories and added sugars consumed in SSBs can significantly reduce the risk of obesity, Type 2 diabetes, and other chronic diseases including heart disease and some cancers. Further, SSBs are the number one risk factor for dental caries (tooth decay) in children and youth.

Healthy hydration improves cognition and attention and can even improve students’ test scores. It allows organs and body systems to perform at their best. Plain water works to rinse the mouth and, when it is fluoridated, to strengthen dental enamel. Yet, studies show that schoolchildren are often under-hydrated (Drewnowski, Kenney).

Hydrating with tap water is more than a healthy choice. It is environmentally friendly (packaged beverages have a larger environmental footprint, particularly those with added sugars, acids, or flavors) and more equitable (not all children and families can afford to purchase bottled water).

Recognizing the risks of over-consumption of SSBs and the health benefits of drinking water, public health experts and a network of advocates are working to assure that kids in school can not only can access water easily but also will choose to drink it. Studies show that with improved access to water and drinking water education and promotion, children’s water consumption increases and body mass index decreases (Mucklebauer, Kenney).

Drinking Water in School: The Requirements

The National School Lunch Program (NSLP) operates in nearly all public schools and requires “that schools make potable water available and accessible without restriction to children at no charge in the place where lunches are served during the meal service.” In addition to the NSLP-compliant water source, state plumbing codes require a certain number of drinking fountains per capita.

Beverages are also regulated by Smart Snacks protections which restrict availability of sugar-sweetened “competitive” beverages (i.e., beverages sold on campus) and permit sales of bottled water.

50.7 million children spend a good portion of their waking hours in our nation’s 98,000 public schools. School day breakfasts, lunches, and snacks are all opportunities for students to have something healthy to drink, and sports and recess times should be too.

The Importance of Safe Tap Water

When promoting tap water for children, we want to be confident that it is safe. The crisis in Flint, Michigan, as well as media coverage of tap water contamination incidents, highlight the fact that there are times and places when tap water is not safe. Contaminants sometimes present in source water can increase the risk of certain cancers and harm reproductive health. Lead in drinking water is also a concern.

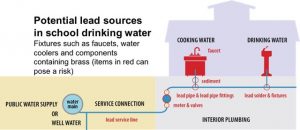

Lead is a toxin that, even in small amounts, reduces IQ. At higher levels, it can harm reproductive and other organ health and is linked to criminality and other antisocial behavior. Most of the time, when children have elevated blood lead levels, the source was lead in dust, soil, or old paint. However, lead can be present in plumbing parts, especially older plumbing, and this lead can leach or flake into tap water. It is important to reduce all exposures to lead, including in drinking and cooking water.

Extent of Unsafe Tap Water in Schools

Ninety percent of schools in the U.S. receive their water from a local public water utility. The remainder source water from their own well. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) records of utility compliance with the U.S. Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA) suggest that about 95% of utilities provide water that meets standards for a wide range of contaminants including such common ones as arsenic, nitrates, and disinfection by-products. Notably, there are areas of the country, often rural, where these quality standards are violated, and good data on well water quality is sparse.

Once water leaves utility mains and enters a service line and then building plumbing, it can be exposed to lead, if lead is present in any plumbing parts. Water that sits “stagnant” in lead-containing plumbing can absorb lead, and if lead-containing pipes or fittings are corroded they can yield tiny particles of lead into water. Utilities treat water to minimize corrosion but (as was the case in Flint), not always effectively. Regulations have progressively lowered the amount of allowable lead in plumbing parts; however, especially in older schools, lead-containing plumbing can be present.

Plumbing graphic adapted from Families Against Chemical Toxins

Starting in 2016, a number of states took action with legislation or developed other programs to perform widespread testing for lead in school tap water. These initiatives are beginning to give us critical information on the magnitude of the problem of lead in school tap water. Full analysis of these testing data is needed, but preliminary reports suggest three conclusions:

- The problem is widespread enough that no school should assume every tap yields safe water all the time.

- Taps yielding water with elevated lead levels are few enough that schools should have confidence they can tackle and deal with the problem.

- Tap water lead testing, when done correctly, reveals “worst case” lead levels. Most of the time, most taps being actively used will provide water meeting SDWA standards.

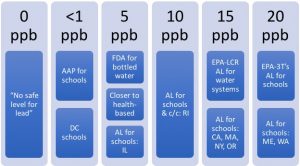

One critical issue stands out: the level of lead in tap water that is deemed “safe.” U.S. Environmental Protection Agency standards set 15 parts per billion (ppb) of lead in a liter of water as the “action level.” Yet the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends a goal of 1 ppb for lead in school drinking water. Some states have set different action levels; bottled water is required to have 5 ppb or less of lead. Similarly, we must continue to improve tap water quality through regulation of emerging contaminants and increased protections for source waters (e.g., groundwater, rivers, lakes, watersheds).

Chart by Nutrition Policy Institute, University of California

What Can We Do About It?

Every school should be able to provide quality tap water access. To achieve this goal, we need national consensus on testing protocols and an action level, and we need to assure that schools have the resources, both financial and know-how, to assess and improve school water quality. Researchers, advocates, school personnel, and industry partners are actively working on these elements and there is significant progress in knowledge and responses.

Case Study: Lead Reduction

Chicago Public Schools (CPS) provide an example of a district that has taken the bull by the horns to reduce the risk of lead exposure in school drinking and cooking water. CPS Engineer Rob Christlieb recently presented in a webinar on solutions for school tap water safety.

CPS tested all taps in all schools – and not just one first draw sample, but five sequential samples at each tap. CPS made use of traditional lab-based testing as well as new technology, ‘Palintest’ site-based testing. Results helped to pinpoint many lead sources in plumbing and led to a program to remove and replace these parts. CPS considered installation of point-of-use filtration as an additional precaution but concluded that regular “flushing” of their pipes would be both effective and cost-effective. A creative district engineer then invented a timer device that turns on automatic flushing for all taps at the flip of a switch. CPS is now looking at reducing their action level from the current Illinois standard of 15 ppb to 2 ppb.

Case Study: Other Contaminants

The water that some schools in the Central Valley of California receive from their local utility is contaminated with naturally-occurring arsenic, nitrates, or other contaminants from fertilizer run-off in this rural, heavily agricultural region. In the Agua4All project, the Rural Community Assistance Corporation, with funding from state health insurance conversion funds through The California Endowment, has installed “hydration stations” that provide filtered, chilled water in schools and other community locations. Not only is the water safe, but evaluation shows that education and promotion effectively raises consumption of water instead of SSBs.

Other Actions to Turn to the Tap

There are many ways for school communities – leadership, administration, staff, teachers, students, and parents – to improve school drinking water and help build healthy hydration habits.

- If your state currently has a voluntary testing program for lead in school tap water (find out here), encourage your district to take full advantage.

- Make sure access to quality tap water is a part of your School Wellness Policy.

- Use National Drinking Water Alliance resources to build effective access to water at your school.

- Educate your school community about the health benefits of switching to water as First for Thirst instead of SSBs.

- Promote drinking water with these resources.

Studies show that with improved access to water and drinking water education and promotion, children’s water consumption increases and body mass index decreases. Coupled with the cognitive, oral health, “green,” and equity benefits – these are all good reasons to turn to the tap at your school!

If you are interested in learning more about improving access to quality water in schools, or have suggestions for needed resources, please visit our website, DrinkingWaterAlliance.org, or contact us at DWAlliance@ucanr.edu.

References

Reedy J, Krebs-Smith S. Dietary sources of energy, solid fats, and added sugars among children and adolescents in the United States. J Am Diet Assoc. 2010; 110: 1477–1484.

Drewnowski A, Rehm CD, Constant F. Water and beverage consumption among children age 4-13y in the United States: Analyses of 2005-2010 NHANES data. Nutrition Journal. 2013; 12(1): 1-9.

Kenney EL, Long MW, Cradock AL, Gortmaker SL. 2015. Prevalence of Inadequate Hydration Among US Children and Disparities by Gender and Race/Ethnicity: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2009–2012. Am J Pub Health 105 (8):113-e118.

Rebecca Muckelbauer, Lars Libuda, Kerstin Clausen, André Michael Toschke, Thomas Reinehr, Mathilde Kersting. Promotion and Provision of Drinking Water in Schools for Overweight Prevention: Randomized, Controlled Cluster Trial. Pediatrics Apr 2009, 123 (4) e661-e667; DOI: 10.1542/peds.2008-2186.

Kenney EL, Gortmaker SL, Carter JE, Howe CW, Reiner JF, Cradock AL. 2015. Grab a Cup, Fill It Up! An Intervention to Promote the Convenience of Drinking Water and Increase Student Water Consumption During School Lunch. Am J Pub Health105(9):1777-1783.

Author Bio

Christina Hecht is Senior Policy Advisor at University of California’s Nutrition Policy Institute (NPI). She leads NPI’s work in drinking water access and consumption, including NPI’s role as the hub for the National Drinking Water Alliance, a network of individuals and organizations across the United States working to ensure that all children in the U.S. can drink water in the places where they live, learn, and play. She is a co-investigator in current research on drinking water and is active in multiple collaborative projects. Dr. Hecht graduated from Stanford University with a B.A. in Human Biology, and from the Johns Hopkins School of Hygiene and Public Health with a Ph.D. in Population Dynamics.