By. Drew Hirshon

Innovation, by definition, is making something new or better. In essence, education is in an innovative state because the world is transforming before our eyes. If we as educators don’t evolve, we will be sending our students into the workforce with skills not suitable for the 21st and 22nd centuries. Today’s youth will enter tomorrow’s workforce needing to be nimble with success skills (e.g., collaboration, critical thinking/problem-solving, communication, time management) and familiar with robotics and coding. As educators, where do we begin? How can I implement new and innovative classroom strategies to foster an entrepreneurial mindset? What pitfalls might I encounter and how can I avoid them? These and many other questions came to mind as I thought about changing my pedagogy to better prepare my students for the real world.

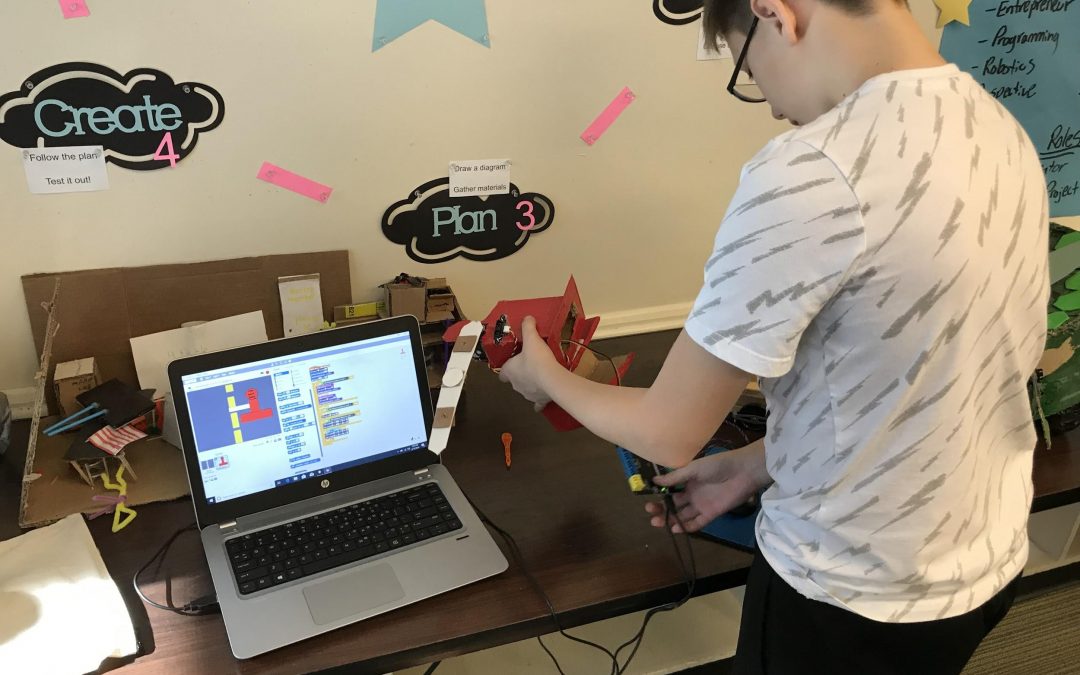

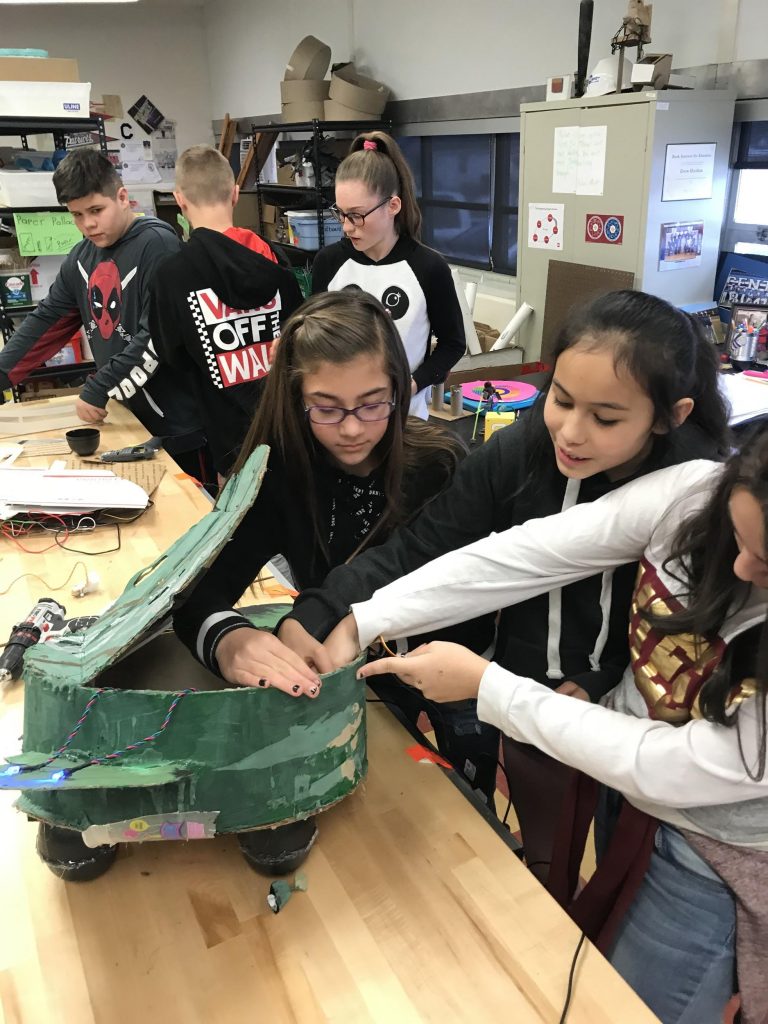

This article discusses some of the steps I took to ensure success in planning and implementing a project called “The Next Best Thing.” My fourth- through seventh-grade students at the Pueblo School of Arts and Science – Fulton Heights in Pueblo, Colorado went on a journey assuming the role of an entrepreneur. They researched and selected a problem they could find a solution for while using robotics to create a prototype of their solution to present to a target audience. It was important that students had empathy for their end user (target audience) and asked the right questions so that they could meet their end users’ needs appropriately. To accomplish this challenge, students had to develop necessary success skills and content knowledge.

Planning and Ideation

The planning of an innovative project can begin in a multitude of ways. Sometimes it begins with a solid project idea; other times it starts with a strong driving question. Most importantly, it should always begin with “meaty” learning goals and success skills in mind. In my project, I started with the learning goals I wanted to address. Design thinking is at the heart of my classroom content, and I wanted to bring in robotics and other technology tools, such as Google Suites and CAD software, that students could use to collaborate, research, plan, and ultimately bring their final design plans to life. Next, I created a driving question that would capture the hearts of my students and engage them in the project’s idea and the content that would be addressed. The driving question I landed on was, “How can we as entrepreneurs use robotics to solve a problem in our community or world?”

Scaffolds

Equity in education is something I am very passionate about. As I start to flesh out my projects, I make sure ALL of my students have access to the resources they need to be successful in the project. With that being said, I always try to think about my students individually and embed scaffolds that all students can benefit from, especially those who are furthest from opportunity. In this project, I used a digital planning tool that students accessed as a team to document all steps from inquiry and research, to brainstorming and planning, to creation and improvements. I also ensured that I had checklists for specific steps within the project, such as writing the problem statement, and a final design rubric so students had a clear target from start to finish.

Project Ideas

Using the design process helped students find their focus and an area of passion that would solve a problem and be sustainable for the planet. Many students leveraged biomimicry, or innovation inspired by nature, as the basis for their projects. Some examples:

- A group of sixth-graders was inspired by the albatross to design a desalination cup that would help individuals living near salt water be able to drink clean water.

- Another group of sixth-graders used recycled materials to design a more cost-efficient prosthetic arm for our armed forces.

- A group of fifth-graders designed a backpack inspired by ant legs to help service workers lift heavy loads, such as when rescuing humans from burning buildings.

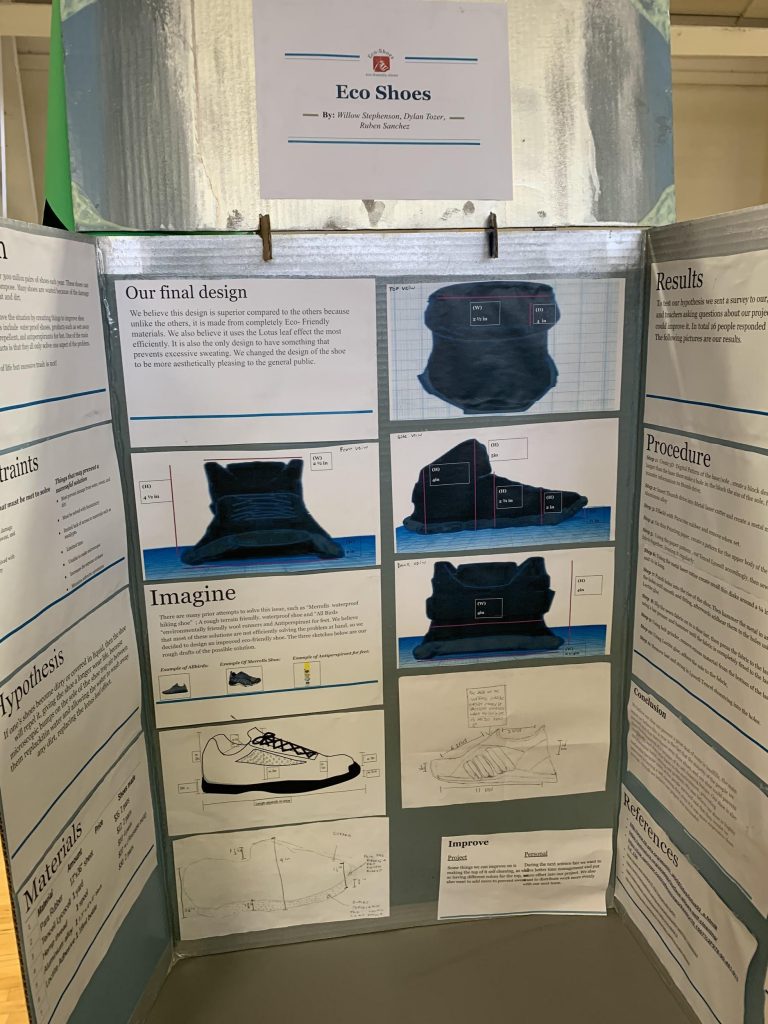

- A group of seventh-graders came up with the Eco-Shoe, a plant-based product that uses the lotus effect to keep the shoes cleaner for longer.

As you can see, when you give students voice and choice when it comes to project ideas, their passions will drive deeper learning.

Critique and Revision

To get high-quality work, I give students opportunities to give and receive feedback using rubrics, and from multiple perspectives. Giving and receiving feedback can be tricky especially if you haven’t built a classroom culture to do so. We follow Ron Berger’s advice and have built a culture of giving feedback by being “Helpful, Specific, and Kind.”

In this project, we used two feedback protocols from the National School Reform Faculty. The first is the Charette protocol. The process starts with a presentation, then a focus question to get the audience to give feedback on that specific topic or idea. The audience then gives their feedback and the presenter listens. Lastly, time is left for open discussion before switching roles. I have found that when protocols and feedback are modeled, students feel a sense of agency and see the value in giving feedback and gaining insight into other perspectives. Now that students see the value in feedback, they often drive that process, asking me when our next round of feedback will take place. They understand their part and that initiating this dialogue doesn’t always come from me. This is a great way for students to give each other targeted feedback and boost performance within their project. We used this protocol after students researched and created their problem statement and had brainstormed three different ideas for their solution. This helped them select the best solution and refine their design based on feedback they received. For example, peer input given to the desalination cup group resulted in a product design that could not only filter out salt but also bacteria and toxins. This would appeal to a larger market and have a worldwide impact.

The second protocol we used was the Tuning Protocol. The Tuning Protocol is done in groups of three and follows a very similar process as the Charrette Protocol but usually allots more time for feedback. This is a much deeper dive into their projects and was used closer to presentation day. At this point, students had created their final design plans in Tinkercad (open source CAD software) and built their robotic prototype using Hummingbird Robotics Kit and Scratch (open source coding software). Along with these two protocols, guest experts from business, sustainability, and engineering fields came in and provided feedback using a design rubric developed by NASA.

Public Audience

Authenticity in projects is what engages and keeps students motivated. A big part of authenticity is knowing their work will go beyond the four walls of the classroom. For this project, students participated in the Regional STEM Faire and Entrepreneur Competition. These opportunities taught students how to present to various audiences and in two very different ways; first through the lenses of a scientist and an engineer at the STEM Faire, and then as an entrepreneur selling the market analysis in the entrepreneur competition. The greatest thing to note here is that ALL of my students had this opportunity, not just a select few. The experience of getting to dialogue and receive feedback from professionals in their respective fields enabled students to envision themselves in those careers one day. My students swept the competition, taking first in the engineering categories even though they competed against high school seniors. Three of our middle school teams now have the opportunity to compete at the state level, and three elementary school teams will compete against high school students in the entrepreneur competition.

Creating these opportunities can be tough because it means you have to develop partnerships and relationships with people in industry. My advice is to simply reach out and “ask.” Many businesses, companies, and professional organizations are looking for opportunities to mentor students. Try to connect and give them specific roles. Remember, they are busy and don’t always have time to ask you how they can get involved. Create a plan, approach them, and see how they can fit into that process. It can be in a mentor role or helping students build new knowledge. Another piece of advice for building partnerships is to join a group. I am part of a group in my community called the Pueblo Makes Group and it’s comprised of “makers” in all realms. I pitch my project ideas to them, and they usually can’t wait to help because they are as excited as I am when kids get to do real work.

Final Thoughts

As I continue to provide students with innovative learning opportunities, I find myself becoming more and more reflective. I embrace the same practices my students use throughout the project in self-evaluation. Some takeaways from my experience are that you have to be ready to give up some of your power. Be willing to step aside and be a coach and facilitator rather than the sole provider of knowledge. You will hit roadblocks just as your students will hit roadblocks. It’s important that you take the time to reflect alongside your students. Don’t be afraid to be transparent when things aren’t going smoothly. Leave yourself room for work days where students can manage their own time but give them tools to do so. I recommend using a Kanban board and PBLWorks team-work report to help scaffold students in managing their time during work time. Early in my project-based journey I didn’t use these powerful management tools, and I found my projects were getting away from me. Deadlines came fast without much to show for it.

I know it can be scary committing to a change in your pedagogy but know it’s what is best for your students to prepare them for what their future holds. When you teach students to think critically and take action, they begin to see themselves as agents of change. Start small by shifting your culture and creating opportunities for voice and choice in your classroom. Give students a chance to have choice in a project’s focus or process, maybe giving a couple learning targets and letting them select what they would like to learn first. Also, develop a classroom mindset that allows for failure as growth versus failure as the end. Finally, don’t be afraid to be vulnerable with your students. When using a new piece of technology, try it first and talk about the pitfalls you experienced. This demonstrates to them the strategies you used to persevere and goes a long way in building relationships and modeling a growth mindset.

Author Bio

Drew Hirshon is a K-8 STEM educator in Pueblo, Colorado. He is also a National Faculty of PBLWorks. Drew believes that all students, especially those furthest from opportunity, deserve high-quality project-based learning and opportunities for deeper learning. He also believes that it’s his duty to prepare ALL learners for the workforce of tomorrow. To accomplish his mission, he creates a classroom culture that fosters a “makers” mindset of empathy, creativity, collaboration, perseverance, and reflection. He hopes that his students will never be afraid to fail because they know they will grow from every experience.