By. Dr. Floyd D. Beachum

Systemic Racism

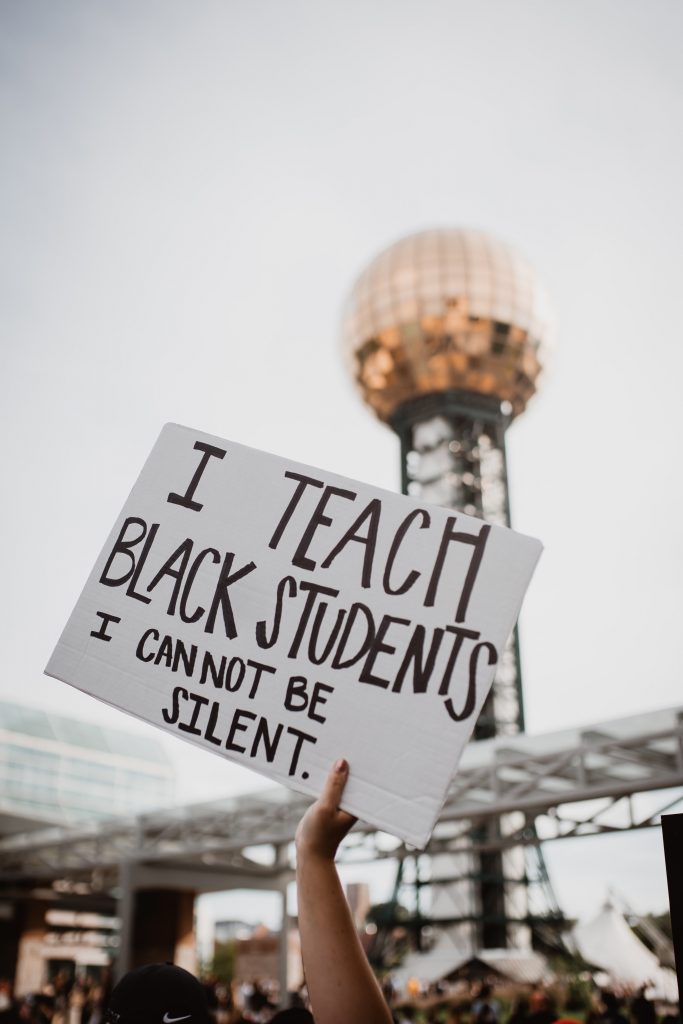

Many people in the United States are calling for the examination and elimination of systemic racism. I define systemic racism here as racism that is historical, individual, institutional, and cultural. In the United States, it’s important to understand how racial history impacts American society. This country was built on the extermination of Native Americans, labor of the Chinese, slavery of African Americans, and so on. This history is not a thing of the past. We cannot romantically look back on history and be proud of the Founding Fathers without recognizing that many of those involved in developing the U.S. Constitution were slave owners. Nor can we look back and be proud of our victories in World Wars I and II without recognizing that many soldiers of color came back home to face bigotry here in America. In K-12 schools, these kinds of historical conversations and facts cannot be omitted from the curriculum. There’s a tendency for teachers to gloss over or ignore content that they don’t feel comfortable teaching. This is problematic because teachers are literally in charge of knowledge construction according to Dr. James Banks. Teachers determine what is worth knowing. School leaders too must be comfortable with or more accustomed to teachers having these kinds of conversations and incorporating the experiences, stories, and contributions of people of color into the curriculum. The legacy of racism lets people omit or rewrite history, which is problematic because it communicates the message that the contributions of certain groups are not important or these conversations are not worth having.

Most people are familiar with how racism plays out on an individual level. These are usually person-to-person interactions based on racial bias, hostility, strife, etc. This is usually viewed as things like police brutality based on race, cross burnings, someone making a racial slur, or calling the police on someone for a frivolous reason (e.g., driving in a certain neighborhood, walking to one’s apartment, having a barbeque in a certain place, or even taking a nap in a certain area). Yes, these are actual reasons why police have been called. In K-12 schools, these one-on-one racial interactions could be called microaggressions. These are more subtle racial insults or verbal assaults (Kohli and Solorzano, 2012). I can recall my experiences going to a primarily white elementary school and being the only Black student in the room. I not only dealt with the pressures of being a student, but the constant comments from classmates about my hair, what part of town I came from, what I supposedly ate, and all of the inappropriate jokes. The impact of this on students over time can be extremely problematic. Furthermore, teachers, staff, and administrators also can engage in these microaggressions, making students of color feel like the school community is against them. Individual racism plays out in very personal ways that impact a person’s sense of self-worth, self-perception, and sense of belonging.

Institutional racism is racism that is embedded in policies and practices. In overt and covert ways, it distributes wealth, opportunities, and social power to whites and limits these same things to people of color. In U.S. society, it can be seen in things like Jim Crow laws that established segregation in the South or redlining, which discouraged people of color from moving into certain all-white neighborhoods (see The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America by Richard Rothstein and The Possessive Investment in Whiteness: How White People Profit from Identity Politics by George Lipsitz). In schools, institutional racism can play out in things like disciplinary policies and decisions that disproportionately affect students of color, ability grouping, tracking, the misplacement of students of color in special education classes, and their limited access to gifted and talented programs. Institutional racism can be hidden in school policies. While the policy looks neutral or non-racial at first glance, it can have a definite racial impact. Administrators should check their discipline data by race/ethnicity and gender to see who is being disciplined the most and for which reasons, and they should determine who is being placed into special education and for which reasons. I would also argue for schools that support full inclusion (see The Principal’s Handbook for Leading Inclusive Schools by Drs. Julie Causton and George Theoharis).

Cultural racism is communicated through broader messages that serve the purpose of promoting white superiority and the inferiority of others. In the past, this was communicated by signs, books, television, movies, and almost every form of media. Nowadays, this includes the Internet, commercials, and social media. In recent years, a number of businesses have apologized for making racist commercials and having them aired. Some of these companies include Dove, Volkswagen, Gucci, and Heineken. I will not mention the number of people who have been photographed in blackface. All these examples send messages of inferiority to primarily people of color. Cultural racism plays out in schools when administrators or teachers engage in behaviors that communicate these same messages. Some schools never hire (or seldom try to hire) teachers of color. Some administrators claim to embrace “diversity” but their students can document overt racist acts. Sometimes it’s even more problematic when school leaders act as a barrier and don’t even entertain the idea that racism could be a factor. Now, to fully understand how this works, we must realize that these four things don’t operate independently – historical, individual, institutional, and cultural racism are intertwined (Schmidt, 2005). They work together and school leaders must be able to identify and deal with all of them. This is where Culturally Relevant Leadership can help.

Culturally Relevant Leadership

Culturally Relevant Leadership is a leadership framework that advocates increased knowledge of diversity, the skills to utilize that knowledge, and the ability to make change and bring diversity to life through leadership actions. School leaders should create a school culture that is equitable and student-centered, so it can lessen the chance of bias, prejudice, or racism among students, faculty, and staff. Leadership is critical when dealing with diversity and school leaders influence school culture. Culturally Relevant Leadership has three elements: liberatory consciousness, equitable insight, and reflexive practice.

Liberatory Consciousness

Liberatory consciousness seeks to raise awareness levels and increase knowledge with regard to diversity in school leaders. We cannot teach or lead without adequate content knowledge. With this knowledge, school leaders can actively promote a critical analysis of beliefs, assumptions, biases, stereotypes, and feelings.

Action Steps: Leaders should read diversity-related texts, attend conferences, form reading groups, create a diversity task force, and invite speakers/experts to address this topic with faculty and students.

Pluralistic Insight

The concept of pluralistic insight leans school leaders toward an affirming and positive notion of students that acknowledges the uniqueness of their experiences and their rich diversity. We all have biases and perceptions, but we also have a greater responsibility to challenge these notions. Eck (2006) bolsters pluralistic insight with four additional ideas:

- Engage and interact with diversity;

- Seek understanding with those who are different;

- Be trust-worthy and reliable; and

- Be open.

Action Steps: Create a journal and catalogue major decisions so you can revisit them. Gather a group of critical friends to discuss diversity or race-related issues concerning your school and act as a sounding board for you. Take the Race Implicit Association Test (IAT) and discuss the results with someone you trust (be open and honest about your results and possible biases).

Reflexive Practice

Reflexive practice views educators (teachers and administrators) as change agents who utilize culturally relevant pedagogy and practices for increased student success. In essence, this idea asserts that educational leaders engage in ongoing praxis (reflection and action).

Action Steps: Leaders should encourage and promote a culture of high expectations for all students by examining discipline data for biases, evaluating special education programs to address over-representation and adequate service delivery, conducting an equity audit, and making sure educational equity is part of the school’s mission, vision, and/or values.

Conclusion

According to Victor Hugo, “All the forces in the world are not so powerful as an idea whose time has come.” The time has come for the U.S. to live up to our great values of liberty, justice, and equality by making schools places of educational equity where students have an opportunity to reach their potential. School leaders can help challenge the barriers of racism, bias, prejudice, and discrimination by utilizing frameworks like Culturally Relevant Leadership. The time has come; we must be ready.

References

Eck, D. (2006). The pluralism project: What is pluralism? Retrieved from: https://pluralism.org/about

Kohli, R. and Solórzano, D. (2012). Teachers, please learn our names!: Racial microaggressions and the K-12 classroom. Race Ethnicity and Education, 15, 441 – 462.

Schmidt, S. (2005). More than men in white sheets: Seven concepts critical to the teaching of racism as systemic inequality. Equity & Excellence in Education, 38, 110-122.

Author Bio

Dr. Floyd D. Beachum is the Bennett Professor of Urban School Leadership at Lehigh University where he is also the Program Director for Educational Leadership in the College of Education. His research interests are urban school leadership, moral and ethical leadership, and equity issues in K-12 schools. His most recent books include Educational Leadership and Music: Lessons for Tomorrow’s School Leaders (2017) and Improving Educational Outcomes of Vulnerable Children (2018). He is currently working on a second edition of the co-authored book School Leadership in a Diverse Society: Helping Schools Prepare All Students for Success.