By. Jessica Diaz, Sara Diaz-Montejano, Connie Lau, and Francisco McCurry, Environmental Charter Schools

Historically, mainstream environmentalism has informed environmental movements, such as the green schools movement. Yet, mainstream environmentalism has roots in and is dominated by a white, elitist, male worldview (Pulido, 1998; Lewis and James, 1995; Taylor, 2002; Taylor 2015). Rather than critiquing white supremacy and capitalism as systemic forces that play a role in destroying our planet, green and sustainable schools focus on conserving natural resources and stewardship through individual or institutional efforts. Still, this lens negates other forms of honoring and relating to land and living things and erases the histories of non-white and poor people’s relationship to the Earth. If we are to best serve our students, specifically low-income students and students of color, we must implement an Ethnic Studies pedagogy in our schools. This shift to a more critical, interdisciplinary, inclusive, and intersectional lens will greatly enhance the curriculum in green and sustainable schools across the country.

First, one must understand that the history of Ethnic Studies has always been turbulent, from its roots in the 1960s to the battle over the model curriculum in California today. An enduring criticism is that Ethnic Studies is “too political,” but an honest understanding of teaching is that it is a political act (Freire, 1977). From the start, schools have intentionally and explicitly denied education to various groups. From the creation of native boarding schools that removed Indigenous youth from their homelands and punished students because they spoke their mother languages, to Black students being disproportionately disciplined and criminalized (Lopez, 2018), one would be naive to believe that teaching exists in a vacuum. Couple this reality with current views regarding climate change and science, green and sustainable schools must understand that they are political and Ethnic Studies pedagogy embraces and supplements this reality.

What is Ethnic Studies Pedagogy?

Ethnic Studies as a discipline and practice centers the lived realities of various communities of color. This means there are all kinds of histories, narratives, art pieces, and practices that educators “have to” and should pull from to construct units, create essential questions, develop relationships and classroom norms, and produce authentic assessments. It is important here to note the distinction between implementing an Ethnic Studies class versus Ethnic Studies pedagogy across all curricula. According to Tintiangco-Cubales et al. (2019), “Ethnic Studies’ purpose is to respond to students by developing their critical understanding of the world and their place in it, and ultimately prepare them to use academic tools to transform their world for the better” (p. 21). Furthermore, they argue that an Ethnic Studies pedagogy is, “rigorous, culturally responsive, and reflective” to challenge racism and the legacy of colonialism (p. 25). That is why while it is critical that students take an Ethnic Studies class, the work must continue in other classes as well.

Our Context

Environmental Charter High School (ECHS) was established in 2001 with a vision to prepare students for college using an environmental education framework. ECHS is located in Lawndale, California and is primarily Latinx, with a Black and Asian population that fluctuates collectively around 15-20%. Over the past 18 years, ECHS has shifted to integrate Ethnic Studies into its curriculum to meet the demands of its students and staff. The school added an Ethnic Studies class in 2016 and is moving toward an Ethnic Studies pedagogy across all courses. This process includes using professional development time to introduce teachers to resources, hear and learn from guest speakers, and see sample lessons. It has also required teachers to read scholarly articles and hold discussion groups to address implicit biases within themselves and classroom practices.

As the four of us have begun to implement an Ethnic Studies pedagogy on our campus, we have sought to understand how our students conceive of themselves racially, economically, and historically. Using these understandings, we can then support them in developing an analysis with which to see their lived realities. We have changed our content material to cover and center the struggles of people who occupy marginalized identities, such as people of color, Lesbian Gay Bisexual Transgender Queer/Questioning Intersex Asexual (LGBTQIA), women, immigrants, and the working poor, particularly in the United States, with many attempts to connect content directly to the city or county of Los Angeles, where our school is located.

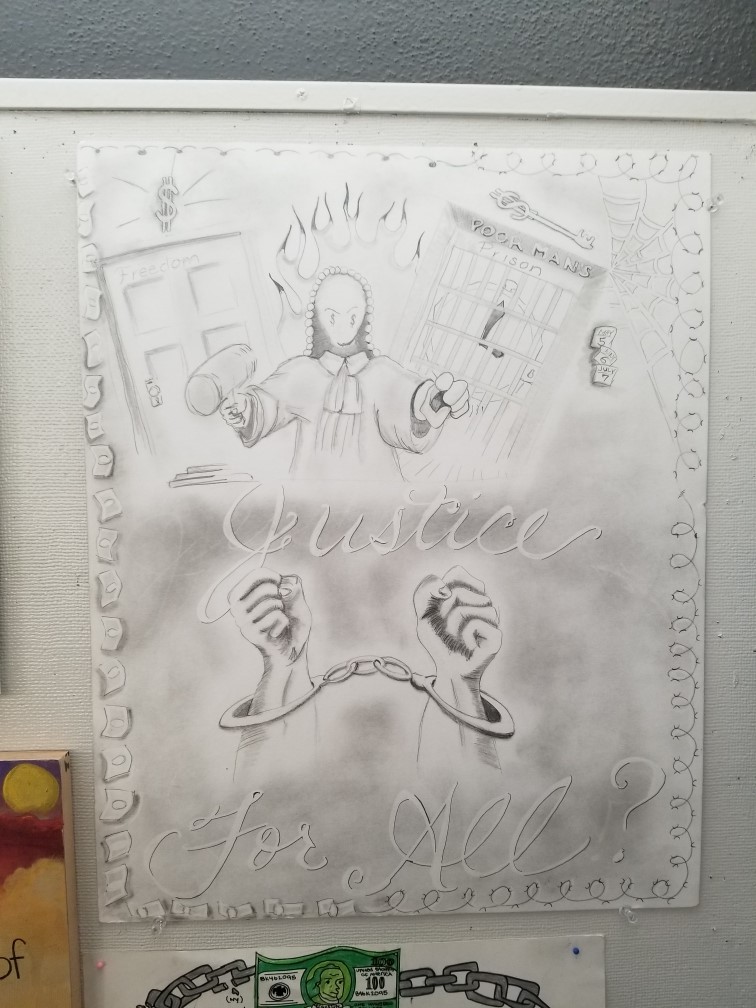

By using an Ethnic Studies pedagogy at ECHS, we cover concepts like power, toxic masculinity, oppression, the core and periphery, the types of borders we experience, religion, desire, healthy and unhealthy relationships, and the law in relation to the body. Through these concepts, students can go beyond what they have learned from their homes, the history of their educational lives, and dominant cultural values and practices to embrace their own agency and power. Our hope is to move toward a communal approach to learning where the teacher is “de-centered” and students are asked to be the information synthesizers and knowledge producers. This work is just starting, however, the evidence that students are engaging more with our classes and understanding the world differently is already surfacing.

Opportunities and Shifts in Instruction

Grade 9-12 Interdisciplinary Instruction

As Ethnic Studies pedagogy has begun to appear across our campus curricula, we have experienced shifts in our benchmark interdisciplinary projects. In ninth-grade, students are no longer thinking about living in tiny homes but rather are asked to imagine how to reuse vacant lots in an area that experiences the heat island effect and hotter summers due to climate change. Students learn about resistance movements that include land issues and apply this history to their final projects. They also include a community asset map in their findings to make decisions about what they propose to build. In tenth-grade, students think about what Los Angeles needs to be a sustainable, accessible, and equitable city of the future, while taking into consideration narratives from the “core and periphery” of the region, as well as the natural world that was here first. Students use class and race analysis to implement solutions that will allow their city to thrive.

Environmental Science students look at data maps that identify petroleum refinery locations in Los Angeles County and comment that the disparity in placement and pollution is “an example of systemic racism.” Teachers comment on how students incorporate language from their Ethnic Studies course into their interactions at school and when thinking through topics in other classes. They say things like “that’s dehumanizing, stop it” or “I think he has internalized oppression.” When discussing this article with the school librarian, who supports many of our students through their senior thesis research projects, she said, “what I love best about it [Ethnic Studies pedagogy] is that students now have language to say what they have been feeling.”

Over the past several years, the topics of our culminating senior thesis research projects have shifted from things like steroid use, video game addiction, and testing consumer products on animals, to Mexico’s historical violence and Ayotzinapa’s state-sanctioned disappearance of 43 students, hypermasculinity and how it impacts LGBTQIA youth and women, and barriers to the two-state solution between Israel and Palestine. The work has been incremental and slow, but visible.

Beyond College Visits

For the past two years, a group of teachers and counselors have reinvented the typical “outdoor trips” that were common at ECHS: trips to Idlewild, Joshua Tree, and Yosemite. These educators designed an urban college tour experience for students interested in attending schools in the northern regions of the state. The tour includes stops in Merced, Berkeley, Oakland, San Francisco, and San Jose. Students learn about the history of those campuses in relation to students of color, the make up of surrounding communities, the different resources and organizations available to them, and cultural areas such as nearby parks, galleries, restaurants, and music events. In this way, students are able to preview what life would feel like on that campus and in its surrounding community. While one of the trip’s goals is to introduce students to various college campuses, the teachers and counselors who planned the trip intentionally built in opportunities for solidarity building across various ethnic and racial groups. The trip also allows students to look at other urban environments and expand their notions of what it means to be outdoors.

Changes to Our Mission Statement

The work of various educators across the Environmental Charter Schools organization has impacted our common mission statement. Once only focused on how environmentalism can be used to give students of color access to green space and higher education opportunities, our mission now includes a social justice element that calls for students to use the tools and knowledge they gain to create change within their communities. This small textual gesture is critical to framing the type of work that veteran teachers and new hires can do on campus.

The Limits and Possibilities of Ethnic Studies

Critical pedagogies like Ethnic Studies can give us lenses through which we can make sense of the world and act upon it. While Ethnic Studies is a transformative pedagogy, it hasn’t explicitly provided us with a lens with which to think about the land as more than just something we do or don’t have a right to own. Indigenous scholars have called for the need to include Indigenous sovereignty and land sovereignty into conversations of liberation. Sandy Grande’s (2004) Red Pedagogy: Native American Social and Political Thought pushed us to think about the shortcomings of critical pedagogies, such as Ethnic Studies, pointing out that so much of it was and is still rooted in Western frameworks. For those of us who teach non-Indigenous youth from marginalized communities, we are also in need of a pedagogical structure that allows us to examine the ways in which we participate in the ongoing erasure of Indigenous people and in the colonization of Indigenous lands. This is particularly important for green and sustainable schools whose curriculum, trips, and projects are land focused. We must ask, what pedagogies can we pull from that allow us to be in solidarity and in relationship with Indigenous people, and to see the land as its own entity and as integral to our lives?

While Ethnic Studies in some instances frames the environment in Western ways, throughout its existence it has demonstrated its ability and willingness to change, to be a pedagogy of possibility. We believe that green and sustainable schools can be expanded in critical ways by adopting more of an Ethnic Studies pedagogy; however, so can Ethnic Studies be expanded to include environmental ways of thinking that challenge, disrupt, and reimagine white, elitist, and male worldviews to create one where the transformation of our students’ lived realities and the Earth’s well-being go hand-in-hand.

Works Cited

Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the oppressed. New York, NY: Continuum.

Grande, S. (2004). Red pedagogy: Native American social and political thought. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

Lopez, G. (2018). Black kids are way more likely to be punished in school than white kids, study finds. Vox. Retrieved from: https://www.vox.com/identities/2018/4/5/17199810/school-discipline-race-racism-gao

Lewis, S. and James, K. (1995). Whose voice sets the agenda for environmental education? Misconceptions inhibiting racial and cultural diversity. The Journal of Environmental Education, 26(3), 5-12.

Pulido, L. (1998). Economic and environmentalism and economic justice: Two Chicano struggles in the Southwest. Tucson, AZ: The University of Arizona Press.

Taylor, D. (2002). Race, class, gender, and American environmentalism (Gen. Tech. Rep. PNW-GTR-534). Portland, OR: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station.

Taylor, D. (2014). The state of diversity in environmental organizations. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan, School of Natural Resources and Environment.

Tintiangco-Cubales, A., Kohli, R., Sacramento, J., Henning, N., Agarwal-Rangnath, R., and Sleeter, C. (2019). What is ethnic studies pedagogy? In T. Cuauhtin, M. Zavala, C. Sleeter, and W. Au (Eds.), Rethinking ethnic studies (pp. 20-25). Milwaukee, WI: Rethinking Schools.

Author Bios

Jessica Diaz has been with Environmental Charter Schools since 2015. Jessica taught science and was an instructional coach for the past nine years. She also helped coordinate the Green Ambassadors Institute from 2015 – 2018 and, with this same team, helped write and publish environmental education curriculum. Jessica believes that students must have the opportunity to develop their own research and that through this students will find solutions to some of the toughest problems in the coming years.

Sara Diaz-Montejano serves as the Social Justice & Equity Coach at Environmental Charter High School (ECHS). She joined ECHS as a teacher in 2012 and is currently working on her Ph.D. in Urban Schooling at UCLA. Her research interests include environmental education, bilingual education, and healing. She is passionate about justice and hopes to be part of constructing “a world where many worlds fit.”

Connie Lau teaches Ethnic Studies 9 at Environmental Charter High School and has been teaching there since 2015. She is passionate about being a critical educator who guides students to read and transform the world. She is at Environmental Charter Schools because of her passion for project-based, experiential, and outdoor-based learning.

Francisco McCurry teaches English 11 at Environmental Charter High School. He has worked in education for a decade. This will be his fourth year with Environmental Charter Schools. Francisco believes sharing the tools to imagine, read, and create ourselves into the future are essential to a collective project toward justice and liberation. His fiction, literary criticism, and music reviews have been published at Queen Mob’s Teahouse, Lunch Ticket, Buzzfeed, 5th Element, and PIMB. He is a native of Los Angeles County, having been raised in Van Nuys and grown up in Palmdale. He currently lives in Gardena, California.