By. Kimberly Pettigrew, Director of Community Health Programs, Tennessee Clean Water Network

A large McDonald’s sweet tea contains as much sugar as an entire apple pie. A 20 oz. Dr. Pepper contains as much sugar as 6 ½ Krispy Kreme donuts. Even a 20 oz. Gatorade contains nearly as much sugar as students should consume in an entire day. It is no surprise why our country is in a health crisis when you look at our beverage intake alone.

Obesity rates have tripled among children since the 1980s, and if the trend continues, children today could be the first to live shorter, less healthy lives than their parents, says the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

In Tennessee, children ages 10-17 rank number one in the nation for obesity and overweight. While obesity is a complex problem with many contributors, changing what to drink is a simple, straightforward way to dramatically improve health. Encouraging drinking water in place of one sugary drink per day could create a healthy habit that lasts a lifetime—and it’s a simple change to make.

Forging these new healthy habits, however, is near impossible if students do not have free and convenient access to appealing sources of drinking water and if they do not understand the importance of choosing water over sugary drinks. The Tennessee Clean Water Network (TCWN) believes access to free drinking water in schools is the first strategy for helping young people to increase their water intake, which may reduce childhood obesity and improve students’ thinking and learning abilities.

The School Beverage Environment

Our journey began by conducted surveys of students’ perceptions of drinking fountains at schools. As expected, students (and teachers) complained about fountains being “dirty” and “gross” or they thought it would “make them sick.” Students also complained about not being able to drink enough water from the fountains during breaks.

It is easy to see why students feel this way when you see the fountains in their schools. Many of the fountains in the poorest communities and schools are at least 50-60 years old. Some of the fountains are even falling apart or provide hot, undesirable drinking water. TCWN even saw a fountain that required two people to use it, because it shot water across the hall.

Fortunately, our legislators and educators have attempted to improve nutrition conditions in schools. All schools that participate in the National School Lunch Program or Federal Child Nutrition Programs must establish a local school wellness policy for all district schools. The wellness policies set requirements for school nutrition and physical activity standards including: policies for competitive foods and beverages, sugary drink standards, modeling healthy behaviors, and access to water.

TCWN has conducted numerous surveys about beverage environments in school districts across the state to assess the success and implementation of local wellness policies. Despite the Federal requirements, we have seen schools that do not offer water as an option for students during mealtimes and schools that still have sugary drinks in vending machines for students. We have even realized that the “healthy” juices and milks that students are offered (or required to take) at mealtimes, snacks, and after school programs can lead them to consume 120g of sugar in one day from beverages alone. That is more than three times the recommended amount of sugar a student should consume in a day!

Taking Action to Improve Beverage Access in Schools

Clearly, changes still need to be made to school beverage environments to improve health and behavior. TCWN believes the first step can be a simple one to make—ensuring students have access to clean, free drinking water during meal times and throughout the school day. That is just what our Bringing Tap Back program seeks to accomplish for nearly 1,000,000 school-aged children in Tennessee.

A study by researchers in Pediatric Obesity, as highlighted by CardiovascularBusiness.com, states

“It’s estimated that 570,000 fewer U.S. children would be overweight or obese if water dispensers were installed in school cafeterias across the country, resulting in $13.1 billion in medical and indirect societal cost savings.

The findings were based on 2009 to 2013 data involving 1,200 elementary and middle schools in New York City and showed that students in schools with water dispensers had a threefold increase in lunchtime water intake, significantly lower whole-milk consumption, and a small but substantial drop in overweight risk after a year.”

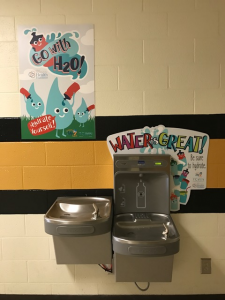

TCWN’s Bringing Tap Back Program began in 2013 with a grant from the Tennessee Department of Health’s Project Diabetes Program. The program has used water bottle refill stations and health message materials to provide access to clean, free drinking water and messaging to encourage water consumption, respectively.

Schools who join our program receive a filtered, chilled Elkay water bottle refill station that includes a traditional fountain and a portion that offers a hands-free bottle filler. The stations even track the “number of water bottles saved” to emphasize the environmental impact of bottled water.

Our program also places a heavy emphasis on health messaging materials. We provide schools with branded posters and wraps, standard-tailored lesson plans for grades K-6, and materials for high schools to implement a peer-to-peer healthy beverage campaign. Our most popular inclusion is our infographics that can be hung around schools or used on social media and newsletters. We also encourage schools to have a Bringing Tap Back pledge month where students and staff drink one less sugary drink and more water for a 30-day period.

Our measured successes have shown many healthy behavior changes in Tennessee students. By tracking water consumption using the built-in ticker we have learned that all schools have shown increased water consumption. The students in McNairy County, Tennessee drank more than 60,000 20oz. servings of water in one month. In addition to increased water consumption, students in McNairy County also decreased their sugary beverage consumption by an average of one drink per day.

While this small decrease may not seem like it would make a difference, there is evidence that reducing caloric consumption by 50 calories a day (less than one sugary drink) could prevent weight gain in 90% of the population, according to a study in Science Magazine titled “Obesity and Environment: Where do we go from Here” by James Hill.

Benefits Extend Beyond Increased Water Consumption

Teachers have also reported positive changes in their health and classroom behaviors, noting that students are more hydrated thanks to the refill stations. They have noticed students are more focused and attentive in the classroom. Some teachers at Michie Elementary School even reported improved test scores by as much as one letter grade in their classes.

One teen, Marsela Barboza, who uses the refill stations at her school and participated in our health activities saw a change in her physical appearance—she lost 7 pounds in the first 30 days. And one junior, who has type II diabetes, reported having more success in adhering to his diet plan.

Another teen, Jameson Simms, shared this personal success story: “My girlfriend, Becca Johnson, took the Sodabriety pledge with me to eliminate sugary drink consumption. The two of us lost over 5lbs each.” He continued, “When the campaign ended, I tried to drink sweet tea, but it ended up just making me sick because my body was no longer used to it. I’m definitely going to continue my own personal campaign against sugary drink consumption.”

Water Refill Stations Also Filter for Lead

While encouraging children to choose water over sugary beverages is important to their lifelong health, we must first ensure that their sources of water are clean and safe for drinking.

90% of schools in the United States are exempt from lead testing under the Federal Safe Drinking Water Act and the Lead and Copper Rule because they do not have their own drinking water source (i.e. well). Most schools have some dated pipes, fixtures, and plumbing that make them more susceptible for leaching lead into drinking water. Lead is a colorless, odorless, highly toxic substance that causes irreversible damage to children’s cognitive abilities and behaviors.

Many cities and states around the country have already begun proactively testing for lead in schools, including Metro Schools in Nashville, Tennessee. While many of the schools received positive results, a drinking fountain at Hillwood High School registered at 1,190 parts per billion—nearly 80 times the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency action level of 15ppb.

Testing for lead is expensive, but if schools find lead in their infrastructure, the cost to fix the problem can be astronomical. Portland Oregon Schools are spending $28.5 million to mitigate lead infrastructure in their schools over three years.

Fortunately, there is an alternative option that allows students to drink lead-free water while the funds and time to replace infrastructure can be secured.

The Elkay water bottle refill stations used by Bringing Tap Back have the option to have an NSF-certified filter that filters lead. The units are low cost, easy to install, and come in a variety of options for newer and older schools. To date, TCWN has installed 227 water bottle refill stations throughout Tennessee, securing clean drinking water for more than 27,853 students. Our goal is for all students, not only in our state, but across the nation to have access to clean, safe drinking water at school.

Please let us know your concerns and thoughts about lead infrastructure or beverage consumption and health by contacting Kimberly Pettigrew, Director of Community Health Programs, by email kimberly@tcwn.org or visiting tcwn.org.

Author Bio

Kimberly Pettigrew began working as the Director of Community Health Programs for the Tennessee Clean Water Network in June 2015 after serving as an intern under the Bringing Tap Back project. Kimberly works with partnering schools, organizations, and municipalities in communities across the state to provide and promote safe, clean drinking water for Tennesseans. She strives to improve lead infrastructure throughout the state in both schools and communities. Kimberly also serves as President of Slow Food Tennessee Valley and serves on the Knoxville Food Policy Council. She lives on 8 acres in the foothills of East Tennessee and enjoys gardening, cooking, reading, and hiking.